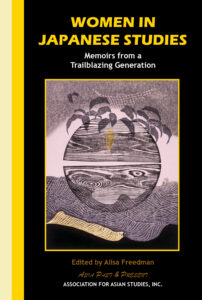

Bringing together stories and reflections spanning more than thirty years, Women in Japanese Studies: Memoirs from a Trailblazing Generation will be released by AAS Publications in December 2023. Edited by Alisa Freedman (University of Oregon), the volume includes chapters from thirty-one scholars, who share stories of achievements, frustrations, and choices—both professional and personal. In Japan and North America, Freedman writes, contributors to the collection “established their careers during an eventful thirty years that indelibly shaped international relations, universities, academic jobs, and women’s roles in the workplace and the family.” A celebration of this generation’s contributions to not only Japanese Studies, but Asian Studies as a whole, this book will educate and inspire younger scholars looking ahead to their own academic careers.

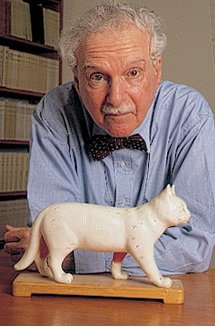

The excerpt below is adapted from a chapter by Barbara Ruch (pronounced “Roosh”), professor emerita at Columbia University and the founder (1968) of the IMJS: Institute for Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives, where she still serves as director. Ruch first visited Japan in 1954, a recent college graduate traveling by freighter to work on postwar relief efforts with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). Returning to the United States four years later, she enrolled in graduate school, first at the University of Pennsylvania and then Columbia University, studying Japanese language and literature. Ruch joined the Harvard faculty before returning to both Penn and Columbia for positions at those institutions. For her pioneering work on Japanese culture, she received the inaugural Minakata Kumagusu Prize (1991), the Aoyama Nao Prize for Women’s History (1992, first non-Japanese recipient), the 42nd Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai (BDK) Award (2008, first female and non-Japanese recipient), the Kyoto Governor’s Culture Award (2011), and other honors. She is the only academic awarded the Imperial Decoration, Order of the Precious Crown, with Butterfly Crest (1999). Since 2006, she has directed the Columbia/Barnard/Juilliard Gagaku-Hōgaku heritage instrumental music performance program.

Day of Infamy

To say that Japanese Studies was conceived in 1941 is not exactly accurate. Affluent elites who had the leisure and the means to satisfy their interests had, since the early nineteenth century, begun their great archaeologies and ownership-assemblage of objects of beauty from Egypt to Japan.

Until bombs and torpedoes did their work, however, Japanese Studies was not a recognized program of academic pursuit in the universities of the world. The fact of the matter is that, without the huge investment of American military money and personnel, it is doubtful that Japanese Studies would exist as it does today in our universities.

The role of the US military as father to Japanese Studies presented me with a dilemma. As an anti-war Quaker, I had gotten into trouble with my peers in high school for refusing to compete for sales of war bonds and stamps, competitions that, after all, were not about selling cookies but were to raise funds to buy bullets, bayonets, and bombs to kill not only enemy soldiers and but also millions of innocent civilians living in their way. With the war over, however, I was forced to view the role of the US military also as a revelation when I realized they had organized, funded, and educated in Japanese language almost every graduate school professor under whom I was to study or whose books I was assigned to read, including Wm. Theodore de Bary, Howard Hibbett, Donald Keene, Ivan Morris, E. Dale Saunders, and Edward Seidensticker.

Home to Philadelphia and on to New York

I lived a lifetime of unforgettable days and years in Japan about which I’ll write one day but not here; it was then AFSC work to repair destroyed lives, not academic.

In Philadelphia in 1958, however, I was lucky, probably beyond anything imaginable today. The University of Pennsylvania’s Oriental Studies Department, world-famous for Ancient Near Eastern and Indian Studies, had recently added Japanese language and literature. They admitted me easily and awarded me a work-study fellowship.

Those were happy days among gentlemanly professors who treated me seriously and shared freely their own excitement about their respective fields. That atmosphere bred in me the desire to continue. How could I stop halfway? I even spent a long sweaty “no-AC” summer in a dorm at Columbia University studying more advanced Japanese language with the kind, severe, magnificent teacher Ichiro Shirato; he gave me a true sense of confidence in the language for the first time and made me comfortable at Columbia. I targeted Columbia doctoral study because of him and the presence of a young assistant professor, Donald Keene, and his awe-inspiring mentor, Tsunoda Ryūsaku. The Ford Foundation was then generously supporting “area studies,” and, after I was vetted by Robert Scalapino, they committed to funding my entire four-year doctoral program at Columbia.

Nowhere in those late-1950s days in Japan and studying in Philadelphia had there been any hint that being a female was a hindrance. Those joyful, carefree days, however, came to an end when I entered my doctoral courses at Columbia, the only woman among a dozen men. Most have now vanished from the scene, but some who became prominent in the field were blatant in their disapproval of me among them: “What are you doing here?” “What do you want?” “You should be at home having babies and not toying with graduate study and usurping grants that are intended for serious men like us.” It was all so adolescent that it did not make me waver; it was just unpleasantly annoying, like flies in summer.

There would be times much later, however, when, with obtuse but I’m sure the best of intentions, women colleagues would tell me how lucky I was not to have had to juggle motherhood with an academic life, as they did, not knowing that the deaths of my two daughters, Laura and Sarah, who had not lived into their childhoods, were never to me a fortunate roll of the dice.

Founding the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture

In the 1970s, Donald Keene asked me to take on one semester of his Columbia courses every year so that he could spend that term yearly in Japan. In the late 1970s, therefore, I commuted to Columbia one day a week. In 1984, I moved full-time to the faculty of my doctoral alma mater, and Columbia agreed to house the IMJS as well.

Despite his worldwide renown, word had come down from on high in 1985 that, when Donald Keene retired one mandatory day not too far off, Columbia would likely not replace him. University needs had higher priority than teaching “the exotic subject” of Japanese literature. Clearly, endowment was the only guarantee of survival and continuity. All agreed, but no one stirred. Others, without their name already crowning something similar, vociferously opposed the founding of a Keene Center. If the IMJS was anything, I thought, it was an engine for cultural rescue. I went around to colleagues’ offices to gather ideas and support.

One prefers to forget the laborious, pitted, and rock-filled road to successful actualization. A certain senior professor knocked the wind out of me with unforgettable words: “You women have too much time on your hands,” he said. “You will fail and you will bring shame to our university.”

This was not male students throwing verbal-harassment spitballs at females. Not annoying flies in summer. This was full artillery from a general. I still have the holes in my heart.

But tenacity is a necessary quality. As is flexibility. So on my own I went to Japan. Major Japanese literary figures, Japanese friends of Donald Keene, some of whom I, too, knew well, joined me in Tokyo to plead the case to the Japanese public.

A year later, with hard work, we successfully raised the several million dollars needed to create an endowed chair, the Shinchō Chair of Japanese Literature for Donald Keene, the anchor for the new (1986) Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture (DKC). Everyone then wanted ownership of the newborn, however. For four years, I served as its director, and after getting programs started, I was able to pass the directorship over to another colleague in 1990. Happily, the DKC has been preserving Japanese literature at Columbia for more than thirty years now.

A Korean nun once said to me, “When you hit an obstacle, become as water and flow around it.”

Excerpt adapted from Barbara Ruch, “‘In Search of Flowers Yet Unseen,’” in Alisa Freedman, editor, Women in Japanese Studies: Memoirs from a Trailblazing Generation (Association for Asian Studies, forthcoming).