By Tina Chen, Jennifer Ho, and Christine Yano

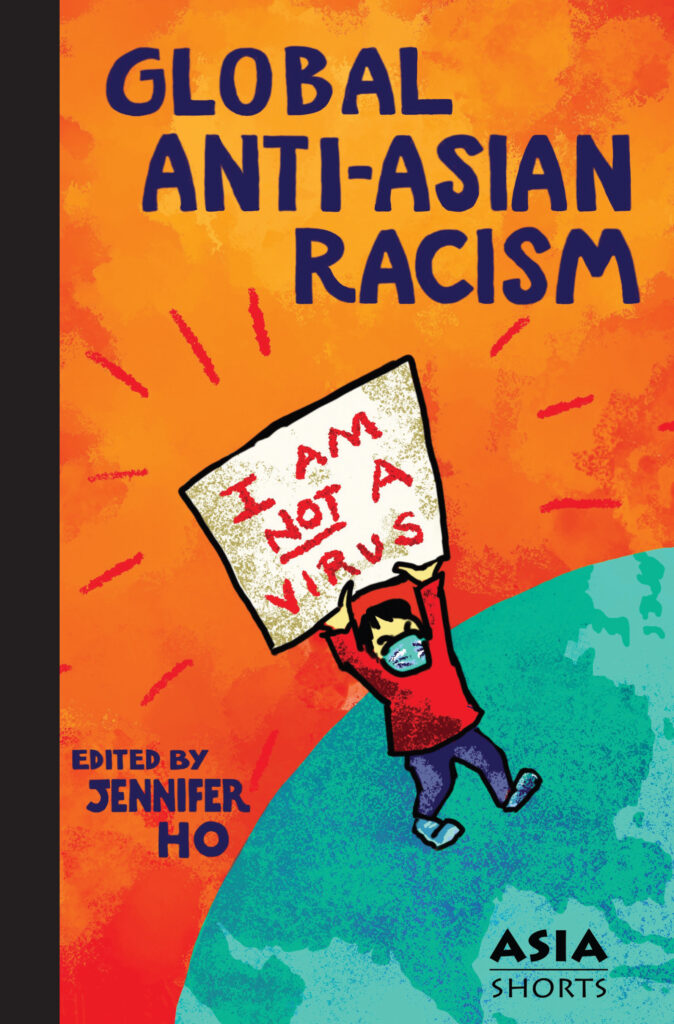

Forthcoming from the AAS Publications Asia Shorts series, Global Anti-Asian Racism is edited by Jennifer Ho, past president of the Association for Asian American Studies and Professor of Asian American Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. This collection features a diverse range of contributions from its 13 authors and touches on anti-Asian racism in locations around the world, including Turkey, Sweden, Brazil, and Africa.

In advance of the volume’s publication, Jennifer Ho convened the conversation below about the book, and the topic of anti-Asian racism more generally, with Tina Chen and Christine Yano. Tina Chen is Associate Professor of English and Asian American Studies at Penn State University and the founding editor of Verge: Studies in Global Asias, as well as the founding director of Penn State’s Global Asias Initiative. Christine Yano is retired from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where she was Professor of Anthropology, and former President of the Association for Asian Studies (2020-21).

To learn more about Global Anti-Asian Racism, please register now for our online book launch, which will be held on Wednesday, February 28 at 2pm Eastern Time.

Jennifer Ho (JH): The topic of global anti-Asian racism seems to hit a nerve with many of us whose research is in the Asian diaspora, especially for those of us Asian identified. I said yes to editing this volume because of the global anti-Asian racism I had witnessed during the height of the COVID19 pandemic, which in the U.S. seemed to hit an apex with the March 2021 murder of eight people in Atlanta, six of whom were Asian immigrant women. What were your own responses and reactions to anti-Asian racism during the height of COVID19? Feel free to share either/both personal/professional responses.

Tina Chen (TC): Congratulations, Jennifer, on this very necessary volume on global anti-Asian racism. It is unfortunate that the COVID19 pandemic created a context for making newly visible the urgency of tackling this topic, but the dynamic of terrible events catalyzing meaningful change is, as you both well know, a critical dimension of the histories of the fields in which we work.

I’m trying to remember how I was feeling during the height of COVID19 and honestly, what I remember (quite imperfectly) is a mix of emotions: sadness, anxiety, ambivalence, and frustration—but also gratitude, admiration, and joy. Some of my sadness and anxiety was a response to the uncertainties of the pandemic as a health problem (what kind of disease event is this? how contagious could this be?); some of it stemmed from how it affected me as someone who is immune-compromised from cancer treatment and my family (this brings back some of how I felt when actively undergoing cancer treatment; I feel bad for my daughter and how her high school experience has been impacted); and much of it was due to the scenes of suffering and devastation to which we were all witness (there are so many people unable to have loved ones with them and dying alone; so now we get a clearer view of how crisis exacerbates the structural inequities created by racism). I think my ambivalence stemmed from my sense of my own privilege during this time, a constant awareness of how the challenges we were all facing were, in my case, very much mitigated by the fact that I could work remotely, I lived in a house that allowed for very comfortable quarantining, my daughter was old enough that I was not having to teach her how to navigate school on Zoom, etc. And my frustrations were multiple, both shared with the world (I guess we are all having to learn a new way of living life and being in the world) and specific (apparently, these are the circumstances that make my expertise as an Asian Americanist of value and how/why do I have to keep explaining to people the history, nature, and vituperativeness of anti-Asian racism?). But there were also so many moments of gratitude, admiration, and joy—for healthcare workers, for activists, for colleagues and friends, for ourselves as members of a community—and I think keeping both the positive and negative emotions in mind has been really helpful for me in figuring out how I want to move forward as a scholar, a teacher, a mother, an ally, a friend, and a citizen.

Christine Yano (CY): Thanks, Jennifer, for starting us off on our conversation. Certainly COVID had a great impact on everyone, but it was startling to feel personal fear for my safety in cities across the U.S. as I realized that I would be in the target group—older, Asian, female. As we all began to travel once again, as I entered airplane cabins with primarily white passengers, as I walked streets far from my island home of Oahu, it felt like a deeper epidemic of fear. I was surprised to hear of anti-Asian sentiments even in my own neighborhood: an isolated comment of “why don’t you go back to where you came from” from a young haole [white] guy—but still shocking in a place with a rich indigenous history and long-standing Asian immigrant cultures.

Professionally, I became President of AAS exactly when the public nation was shut down with COVID precautions. The public nature of holding that position became a series of private-gone-public series of letters to AAS members. Anti-Asian racism is not something that Asian Studies has historically addressed, but it could not be ignored in this context. Here is part of my first letter to AAS members, posted on April 3, 2020:

This kind of [Anti-Asian racist] violence reminds us of ways in which Asians—including those within the geopolitical scope of continental and island Asias, as well as the many diasporic Asians across oceans and continents—may be bound together, not always by choice, but by fiat, through racism. As long as powerful naming practices label a pandemic a “Chinese virus” and thus lay the blame more broadly by association upon something called “Asia,” then Asian Studies must take note and consider such targeted racism part of our kuleana (Hawaiian word, meaning responsibility, concern, stewardship)..

The Association for Asian Studies connects us through kuleana to Asia. That kuleana may be intellectual, emotional, and personal. Some of us are of Asian ancestry and may embrace kuleana on a familial level. Others may not be consanguineally linked to Asia, but share strong affinal bonds. All of us have committed our careers to scholarship on Asia. I ask that we as Asian Studies scholars extend our kuleana inclusively to the many parts of Asias and Asians globally that may suffer as targets of public fears and real human loss.

JH: Thank you, Tina and Christine, for your thoughts, your leadership, and your vulnerability in sharing your recollections of what it was like in the first year of the global pandemic. What you both share resonates so deeply with me—and I’m struck by Tina, the emotions of both despair and elation about all the uncertainty and the generosity that we witnessed. And Christine, you and I both became leaders of Asian diaspora organizations during this period—a challenge and an opportunity to educate widely on these subjects.

My own work has moved more into the public humanities realm, so when I had an initial conversation with David Kenley (series editor of Asia Shorts) I wanted to make sure I could include pieces that were not just standard academic essays. Each of you has also done public intellectual work and/or explored other genres and ways of connecting with people on global Asia and Asian diaspora issues. I’d be interested in hearing your own thoughts about this volume containing multiple genres and the need for us to reach out to both our students and the general public about global Asian issues.

TC: While I haven’t done as much public humanities work as you—especially with the incredible demand put on both of you during the pandemic while leading the AAAS (Jennifer) and AAS (Christine)—I have spent a lot of time thinking about the genres in which we write and work. Some of this was inspired by a stint as interim director of Penn State’s Humanities Institute but the majority of my engagement with diversifying the genres of academic labor and writing has been catalyzed by the work I’ve been doing with/in/for the field of Global Asias. Part of the capaciousness of Global Asias scholarly praxis involves experimenting with form. This is why a distinctive part of the journal I founded, Verge: Studies in Global Asias, is its commitment to making space for scholars to work outside of the constraints of the 30-page research essay. That is an important genre for academic scholarship, to be sure, but it limits much of the work that we can do.

So it is probably no surprise to you to hear that I LOVE that this volume includes multiple genres and is crafted to provide a diverse audience different entry points for accessing the information it contains! I think the volume’s willingness to include different kinds of writing—academic, personal, polemical, experimental, pedagogical, and public (among others)—is critical on a variety of levels. It makes connecting the “academic” conversation to the “public” conversation easier; it enables a more nuanced picture of the really complex contexts, conditions, communities, and circumstances encompassed by global anti-Asian racisms; it diversifies and offers a spectrum of response and engagement that racism against Asians generates. If part of the goal of such a volume is to encourage more conversation between the academy and the public, then the volume’s approach to allowing scholars to approach this task by experimenting with modes of writing that differ from the modes considered “scholarly” is imperative.

CY: Yes, yes—multiple voices, genres, modes. The crafting of this volume by you, Jennifer, is inspirational and aspirational. The trick is to help guide those multiples so that they can intersect productively, so that they can truly hear and feel one another. I think that one of the best and most responsible things that we can do to encourage something called public humanities work is to develop us all as critical listeners. How do we listen—generously, capaciously, critically—to the many voices around us? How do we listen for the silences that may loom large? And how do we listen for—and act upon—unspoken violence that transcends the physical?

JH: Capacious listening. Diverse entry points. Yes—this is exactly what I hope readers who open the volume will take away as some of the many vital approaches to addressing global anti-Asian racism. And perhaps this is a grandiose wish, but I hope this volume also demonstrates that scholarly rigor and research can be found outside of the traditional 30-page essay. I’m so glad that there are venues like Verge and the Asia Shorts series that are open to experimental forms of knowledge production.

You’ve each contributed a generous blurb (in Christine’s case a generous Foreword) about the essays in Global Anti-Asian Racism. I’d love to know what particular essays spoke to you and that you think offer a new perspective on global Asian or Asian diaspora studies. I’d especially like to know which essays you think would work well in an Asian studies classroom that is introducing or centering the topic of global Asian studies?

TC: I loved reading Rivi Handler-Spitz’s graphic essay and think it would work wonderfully in many different kinds of classrooms. Beyond the fact that it is beautifully drawn, the history that it illustrates—that early 20th century script reformers advocated to abolish Chinese characters and considered alphabetization a historical inevitability—is one that complicates discussions of anti-Asian racism in really useful ways. Specifically, it draws attention (pun intended) to a point that you make in the introduction, Jennifer: that “Anti-Asian racism can be internalized by Asian people themselves as well as externalized by non-Asians,” that global anti-Asian racism is a complex phenomenon with no single root cause, that yellow peril sentiment and rhetorics proliferate both within Asia and elsewhere.

CY: I’m going to take the cowardly, but honest, route in saying that the impact of the volume lies in its juxtaposition of these many voices, read forwards, backwards, skipping around. This was my process of reading and learning from it—that is, not linearly so much as reading and then re-reading from another already-read section. For me, the aha moments lay BETWEEN the contributions and then in their stew pot. You, Jennifer, are a master chef!

TC: I think you are absolutely right, Christine. Indeed, the juxtaposition of many voices is wonderfully generative and I couldn’t agree more that the moments BETWEEN are important pedagogical spaces and opportunities!

JH: It’s funny what you both say about the order of the volume—I did spend a lot of time playing around with which essays should begin and end, and which should follow others. I did want Rivi’s essay to land right in the middle—for it to be a little surprise for readers to find a graphic narrative and experience a different mode. And I’m glad to know that both of you feel that there isn’t a teleology to reading the pieces—that they can work in any kind of order and the strength lies in the spaces between—I love that!

You are well known scholars in the fields of Asian studies/Global Asia/Asian Diaspora/Asian American studies. I’d love to hear more about your own work and the ways that this volume on Global Anti-Asian Racism may intersect with the intellectual questions and interventions that you are each trying to make in your professional lives.

TC: One of the things I appreciate about this volume is that it powerfully demonstrates why the kind of multidisciplinary and trans-field approaches I have been advocating for through Global Asias are critical. By approaching anti-Asian racism as a global phenomenon, this volume shows us how exploring vulnerability as the site of both oppression and solidarity requires us to work across and between the academic silos that have historically separated scholars in area studies from scholars working in critical race and ethnic studies. That this demonstration unfolds by encouraging different forms of writing and scholarly praxis directly connects to the book I have just written. Alien Form: Global Asias and Other Speculative Genres of Academic Labor [forthcoming from Duke University Press] argues that theories and concepts of genre and form can be usefully applied in order to re-assess the priorities of the profession. It imagines how a scholarly project that embraces diverse professional activities as part of a connected, differentially coherent practice might simultaneously engender new forms of knowledge and recognize undervalued knowledge practices.

CY: In my mind this volume represents scholarship with an inward- and outward-facing conscience. And this is the direction that I have been heading in my own work. At the University of Hawai`i we have embarked upon a graduate degree in something we are calling “Kuleana Anthropology.” It’s a field that Ty Tengan and myself have been creating on the fly, but in direct response to the call for a greater sense of community responsibility and connectedness. I think smaller island communities raise these issues quite organically—although not without conflict—with the assumption of long-lasting intimate relationships that matter. These relationships need careful tending. Members have to take it upon themselves to tend each other and the greater community/environment responsibly and thereby sustainably. What does this have to do with anti-Asian racism? The call for kuleana can be heard as a widespread call to embrace the responsibilities of freedom, well-being, and social justice in our various fields and beyond. This volume is part of that tending.

JH: I’d like to end by centering the voices and scholarship of our colleagues who have been working on and intervening in global anti-Asian racism beyond the scholars in this volume. Who are the people working on any aspect of global anti-Asian racism that you want people reading this blog to know about (in addition to your own work of course—because each of you has done public work intervening on this topic). Two topics come to mind that perhaps are not natural “fits” to the topic of global anti-Asian racism: scholars writing about climate issues and their impacts on Pacific Island nations. I’m thinking specifically of Craig Santos Perez’s poetry (and I do think of poetry as scholarship) and those working on the history of Japanese American incarceration (Eric Muller’s latest book comes to mind). The volume didn’t take up specifically Pacific Islander/Indigenous issues, but the racism and history of settler-colonialism that Pasifika people live with has everything to do with global racism, especially as climate change can be seen in the dire situation happening in many Pacific Island nations with rising sea levels. And the legacy of incarceration that Japanese Americans experienced in Canada, the U.S., and the Americas is one that needs further investigation and that fits the definition of global anti-Asian racism, especially since it’s not widely known that Japanese in Latin and South America were forcibly removed and placed in concentration camps in the US, some speaking only Spanish. In other words, there are so many aspects to global anti-Asian racism that could fill multiple Asia Shorts volumes, so it’d be great to know about others working on these issues.

TC: Thank you for ending this exchange by giving us the opportunity to draw attention to the work of others! During the pandemic, I was inspired by the work of the Auntie Sewing Squad, a mutual-aid group founded by performance artist Kristina Wong that used their sewing skills to provide masks for the most vulnerable and neglected. They made masks for asylum seekers, indigenous communities, incarcerated people, farmworkers, BLM protestors, and so many others. Those interested in learning more might take a look at two of the texts generated by the group: a performance piece, Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord, and an edited volume, The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice (eds. Mai-Linh K. Hong, Chrissy Yee, and Preeti Sharma; UC Press 2021).

It is sad but true that my schedule these days means that I do not have time to read ALL THE THINGS that I would like to! So I always try to use course prep as an opportunity to sneak in some reading. Right now I’m gearing up to teach a grad seminar on speculative fictions and so just finished reading two books—Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng and Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence—An Arcane History by RF Kuang—that I think speak to the pasts and futures of anti-Asian racism in compelling ways. Ng’s dystopian novel provides a vision of a near future where Sinophobia underwrites the Preserving American Culture and Traditions Act (PACT), an act that “outlaws promotion of un-American values and behavior” and sanctions the removal of children as a means of social control. Kuang’s alternate history imagines a world in which translation—or, more accurately, its impossibility—enables magical power to be harnessed via silverwork to show us how imperial ambition and world-making has always depended on the exploitation and betrayal of Asians (among others). Both novels show the world-making powers of anti-Asian racism even as they create opportunities to highlight the varied shapes that resistance can take, from small inadvertent actions to epic acts of total destruction.

CY: This IS a wonderful way to shore up this dialogue by opening up new avenues of expression. There has been a lot going on in the Pacific and elsewhere that uses the arts as an intervention and tactic. The ones I’m thinking of may not be explicitly and solely tackling issues of anti-Asian racism, but the same kinds of rage against violence underscore their expressions. There is the restlessness of Drew Kahu`āina Broderick, whose works as curator, artist, filmmaker, and provocateur is always pushing and questioning boundaries of intercultural violence, especially in a heavily touristic and military-infused place such as Hawai`i. For example, in the essay that accompanied his co-curation of Hawaiʻi Triennial 2022, Pacific Century—E Ho‘omau no Moananuiākea, “Native/non-Native Artist Collaborations Against U.S. Empire in Hawaiʻi” Broderick writes: “Spikes in hate crime and rising social justice movements bring additional layers of meaning to this ongoing and unevenly distributed moment of social distancing, quarantine, isolation, and death. Coming together, exchanging breath, and supporting caring connections across different identities and boundaries feel as important and dangerous as ever—outcries from communities cannot be ignored, our lives are dependent on one another.” The triennial that resulted featured simultaneously resistance, collaborations, and boundaries across the Pacific—themes shared by this volume on anti-Asian racism.

From my neck of the globe, the more standard (Western-based) divisions of expression are far less important than the shared push and pull of kuleana. Thus, poetry overlaps with song overlaps with dance overlaps with fiber arts overlaps with cuisine, and on and on. Why divide when there is so much more to be gained through the common threads? To Jennifer’s call for shifting the spotlight toward others on the topic of anti-Asian racism, I find greatest solace in these works of beauty, elegance, sensuality, humor, and critique. Is this blend particularly Pacific? Probably not, but they do form a rejoinder to other forms of protest that fill urban streets and mental spaces. They create an emotional and aesthetic centering of the spirit that culls from the natural world around us. In the context of this volume, this is not burying one’s head in the sand, but emerging from the larger loam of hope and humanity. That loam is rich and palpable. Call it kuleana.