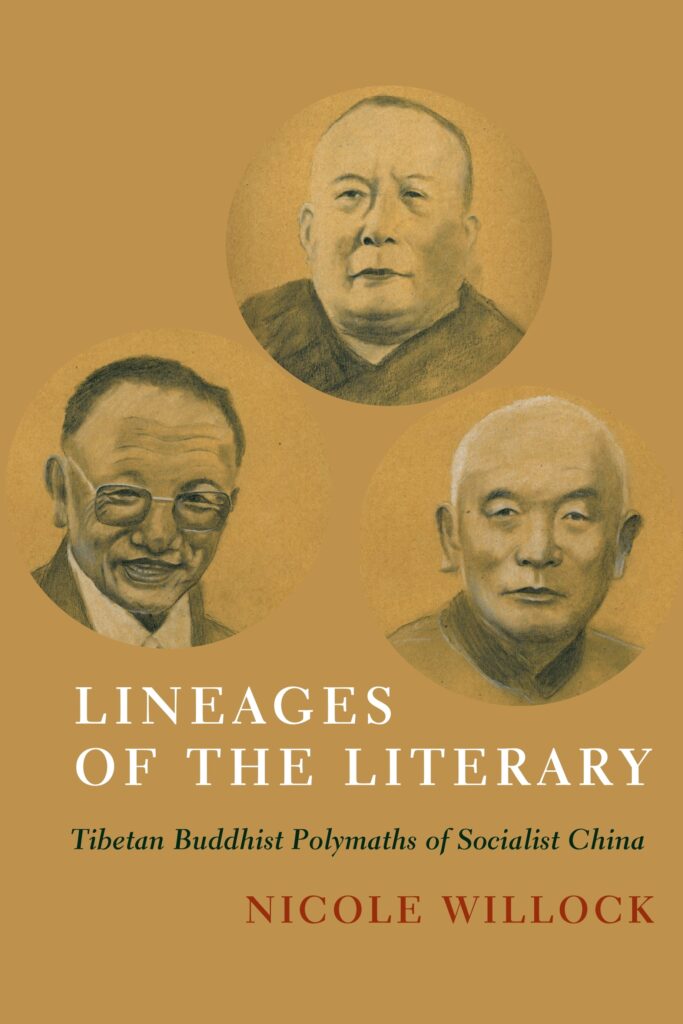

Nicole Willock is Associate Professor at Old Dominion University and author of Lineages of the Literary: Tibetan Buddhist Polymaths of Socialist China, published by Columbia University Press and winner of the AAS 2024 E. Gene Smith Inner Asia Book Prize.

To begin with, please tell us what your book is about.

Lineages of the Literary is about how three Tibetan Buddhist scholars became intellectual heroes in the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C) after 1976. Collectively known as the “Three Polymaths,” Tséten Zhabdrung (1910-1985), Mugé Samten (1914-1993), and Dungkar Lozang Trinlé (1927-1997) earned this symbolic title for their efforts in preserving Buddhist teachings in the darkest hour of Tibetan history. Focusing on the literary productions by these three scholars including: autobiography, Buddhist philosophy, poetic theory, and historiography, I raise analytical questions pertinent to debates on agency, the parameters of religion and the secular, and the contested ground of Tibet. Whereas prevailing state-centric accounts provide leading Tibetan religious figures in China only two roles, that of collaborator or resistance fighter, such a model of agency vis-à-vis state power forecloses the contributions of the Three Polymaths in both the revival of Tibetan Buddhism and the establishment of Tibetan Studies as an academic discipline. By viewing agency in terms of moral capacities of action grounded in their subject formation as Buddhist scholars and within the changing social-political contexts, I offer an alternative model of agency that gives discursive space to how the Three Polymaths alternately safeguarded, taught, and celebrated Tibetan knowledge and practices in the P.R.C.

What inspired you to research this topic?

During my nearly two-year stay as a foreign exchange student studying Mandarin in Chengdu and in Beijing in 1992-93, I was fortunate to travel and spend time in the Tibetan Autonomous Region and in Tibetan cultural areas of Sichuan, Qinghai, and Gansu provinces. At that time, I was quite ignorant of how different Tibetan culture is from Chinese culture and was fascinated by that difference. I started studying Tibetan in Chengdu and as I began to learn more, I drew inspiration from Buddhist teachings in my personal life and resolved to really learn Tibetan language. At that time—in the early-mid 1990s, I got an inkling for the vibrancy of Tibetan intellectual life in China but didn’t understand how that came to be—that was the nascent beginnings of this project—the wish to understand the intellectual traditions in this phase of Sino-Tibetan history. Then after doing an MA with a major in Chinese and a minor in Tibetan in Germany, I decided to move back to the U.S. and began to study Sino-Tibetan relations under the late Professor Elliot Sperling. Meeting Gedun Rabsal, senior lecturer at Indiana University, was the real catalyst for this project. It was through him, and another leading Tibetan scholar in the United States, Pema Bhum, that I learned about the life and contributions of Alak Tseten Zhabdrung, the subject of my dissertation research. The inspiration to continue this line of research for a book project is indebted to Tibetan scholars inside and outside of China.

What obstacles did you face in this project? What turned out better and/or easier than you expected it would?

There were obstacles at various stages of the project. At the beginning it was a little hard to find an academic discipline that fit the materials. In other words, I approached my topic not from the perspective of an established scholarly theory but from reading the Tibetan source materials. This then made it difficult for me to fit my project within the academy because of the predominance of state-centered narratives within scholarship and also because the source materials cross between religious and secular studies. Even though I think of the book as a history, it was only within the disciplines of Religious Studies and Asian Studies that I found an intellectual capaciousness within which these materials could be analyzed. There’s also the obstacle of doing research on Tibet within China with its political instability. I was in Xining on a Fulbright Doctoral Dissertation Research Award in 2008, when in the lead up to the Olympics in Beijing, protests spread throughout the Tibetan Autonomous Region and in Amdo, the eastern Tibetan areas in Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan. For many Tibetans that I spoke to in China, this was about the 50th anniversary of 1958, one of the most harrowing years in modern memory because of the mass collectivization that happened as part of land reforms and also starvation due to Mao’s failed policies of the Great Leap Forward. When the protests started, I had no access to news or the internet. There was a heavy police presence, and I couldn’t go to places that I had planned. I had to change the course of my research project because it wasn’t possible to travel to Lhasa.

What is the most interesting story or scrap of research you encountered in the course of working on this book?

The overwhelming support I have received from so many Tibetans all over the world has been incredible—not strange or funny, but unexpected. There are too many stories to mention here, but I will say for example, I am incredibly grateful for the book’s cover images, which were originally portraits drawn by a young Tibetan artist in China, whom I never met. He had drawn them earlier for his own purposes, and then offered them to me for the book through mutual acquaintances. I am so grateful for this.

What are the works that inspired you as you worked on this book, and/or what are some other titles that you recommend be read in tandem with your own?

This is complicated to answer because my work weaves together different strands of scholarship. Overall, the most influential book on me, especially in the early stages of my project, was Gray Tuttle’s Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China. I also drew inspiration from Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet co-edited by Melvyn Goldstein and Matthew Kapstein. In tandem to my book, I’d recommend reading Melvyn Goldstein’s volumes on the History of Modern Tibet. Tsering Shakya’s The Dragon in the Land of Snows is probably the single most important book on contemporary Tibet and incredibly inspiring. On the anthropological side, I have also drawn inspiration from Charlene Makley’s books and articles and also from Martin Mills’ Identity, Ritual and State in Tibetan Buddhism.

From Religious Studies, I am indebted to Saba Mahmood’s theoretical reworking of agency in Politics of Piety, and scholars working on the politics of religion within China, especially those who acknowledge the important role of Tibetan Buddhists in constructing “religion” in modern China. Holly Gayley’s analytical approach to prioritizing Tibetan narratives in the post-Mao Buddhist revival in her book Love Letters from Golok was also inspiring. Several works in the politics of religion in China also influenced me including The Religious Question in Modern China by Vincent Goossaert and David Palmer, and Making Religion, Making the State: Politics of Religion in Modern China by Yoshiko Ashiwa and David Wank. I just got The Space of Religion, Ashiwa and Wank’s new book, and I look forward to reading that.

Finally, what has captured your attention lately—as a reader, writer, scholar, professor, or person living in the world?

I reflect a lot on the aftermath of the global Covid-19 Pandemic and often think about the massive inequities brought to light by the pandemic, and how we as scholars might mitigate these inequities in some way. I am enheartened by projects such as Every Campus is a Refuge. Moving forward in my career, I am dedicated to promoting gender and social equity whenever I can. This can come in a lot of different ways. I am thrilled to be reading and translating pieces from a 53-volume Tibetan-language anthology on writings by and about women in Tibet entitled Ḍākinīs’ Great Dharma Treasury (Mkha’ ’gro’i chos mdzod chen mo), which was published in 2017 by the Larung Ārya Tāre Book Association Editorial Office in China. Padma’ tsho and Sarah Jacoby introduced the importance of this collection to scholars at the Second Lotsawa Translation Workshop: Celebrating Tibetan Women’s Voices in the Tibetan Tradition held at Northwestern University (October 2022). It’s amazing to read from this work which was edited and published by Tibetan nuns in China. I am also happy to see a growth in the number of Tibetan-language children’s books being published by Mutik Books and TaliTibet. I think that we always have to think about how we can make the world a better place in whatever small way we can.