An Effective but Controversial Ruler

Wu Zhao (624–705), also known as Empress Wu Zetian, was the first and only woman emperor of China. With her exceptional intelligence, extraordinary competence in politics, and inordinate ambition, she ruled as the “Holy and Divine Emperor” of the Second Zhou Dynasty (690–705) for fifteen years. Her remarkable political leadership is recognized and is comparable in some ways to other notable women in later periods of world history, such as Joan of Arc, Queen Elizabeth I, and Catherine the Great. It must be noted, though, that whether completely deserved or not, Wu has a reputation of being one of the most cruel rulers in China’s history. She remains a controversial figure primarily because of stories about her personal actions against rivals. Male Confucian officials who were deeply prejudiced against strong and ambitious women undoubtedly exaggerated this aspect of Wu’s life in later accounts of her reign. Still, there is also substantial verifiable evidence of her ruthlessness toward powerful real or imagined opponents.

The Tang Dynasty

The Tang Dynasty (618–907) is one of the golden ages of China’s history. World history scholar Samuel Adshead has adopted the term “world center” to describe China’s position in the world from 400 to 1000.1 The glory and brightness of Chinese culture during the Tang period was in stark contrast to the Dark Ages in Europe. The so-called “Golden Age” (712–755) emerged shortly following the death of Wu, and Tang China subsequently experienced substantial political, economic, social, and intellectual development.

The Tang was a unified empire, founded by the Li family who seized power during the collapse of the Sui Dynasty (581–618). Li Yuan (later Emperor Gaozu, r. 618–626) and his armies seized the capital, Chang’an, in 617. His son, Li Shimin (later Emperor Taizong, r. 626–649 and future husband of Wu), joined the rebellion. In 618, Li Yuan declared himself the emperor of the new Tang Dynasty. Tang China enjoyed far-reaching diplomatic relations, playing host to Persian princes, Jewish merchants, and Indian and Tibetan missionaries. The scope and sophistication of the Tang Empire’s political development during these golden years was greater than either India or the Byzantine Empire.

During the Tang, the Silk Roads were at their height of influence. During Wu’s life, overland trade routes brought massive entrepreneurial opportunities with the West and other parts of Eurasia, making the capital of the Tang Empire the most cosmopolitan of the world’s cities. Although merchants dealt for and traded many goods, commerce involving textiles, minerals, and spices was particularly prominent. With such avenues of contact, Tang China was ready for changes in society and culture.

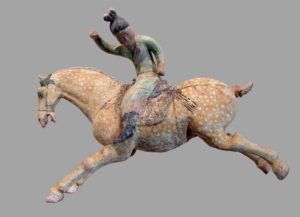

Tang women were assertive, active, and more visible; they rode horses, donned male attire, and participated in politics.

Socially, the position of Tang women was somewhat superior to their predecessors. As Wu Zhao biographer Harry Rothschild has noted, Wu emerged “at the right time” in an incredibly liberal time in China’s “medieval” period.2 Rather than being strictly confined to the inner chambers of dwellings, Tang women were assertive, active, and more visible; they rode horses, donned male attire, and participated in politics. Tang princesses tended to be somewhat arrogant and often chose their own husbands. Some were even as ambitious as Wu in their quest for political power. Such a relatively liberal and open society provided ambitious women like Wu an opportunity to flex their political muscles.

A period of great religious diversity, Tang China was home to Nestorian Christians, Manicheans, and believers in the new faith of Islam. However, three belief systems were dominant: Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. These three metaphysical and philosophical perspectives, though not simultaneously influential, all had important roles in Tang politics. In the Tang period, Confucian scholar Han Yu (768–824) elevated Mencius (372–289 BCE) as the true successor of Confucius, and Han’s emphasis upon the Daxue (The Great Learning) helped pave the way for later neo-Confucian dominance during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). The alleged founder of Daoism was Laozi (sixth century BCE), believed to be an ancestor of the ruling Li family. Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756) promoted Daoism by granting Laozi grand titles and encouraging candidates to prepare for examinations on Daoist scriptures. The Tang Imperial family adopted the Indian import Buddhism, and the dynasty marked the high watermark of Buddhism’s influence in China. By 845, there were 360,000 Buddhist monks and nuns throughout the empire.

Wu Zhao’s Rise to Power

Tang Dynasty founder Li Yuan (566–635) attracted his followers by claiming to be a descendant of Laozi and was well-acquainted with Wu Shihuo (577–635), the father of Wu Zhao. Wu Shihuo—though originally a lumber merchant—was a gifted military strategist and a follower of Tang founder Li in his rebellion against the Sui regime. When the Tang Empire was founded, Li appointed Wu Shihuo President of the Board of Works, a high-ranking post he held for several years. Li later promoted him to governor-general of two important prefectures. The Li-Wu close friendship is also evident in Li’s selecting a second wife for Wu from the Sui royal family, a collateral line of the Yang. Wu Zhao was born of this union in 624.

Emperor Taizong, the second Tang Emperor, and his son, Li Zhi, were both attracted to Wu Zhao’s beauty, intelligence, and spirit.

Historians have been debating the class origins of Wu Zhao since the 1950s. Was she born into a mercantile or an aristocratic family? Wu Shihuo dealt in lumber as an itinerant merchant but also came from a scholar-official family of high local standing that held office under the Sui regime. Later, he became a high-ranking official under Li Yuan. The evidence indicates to this essayist that Wu was indeed born into an aristocratic Taiyuan family in what today is Shanxi Province. However, Wu family relationships were somewhat complicated. Wu Shihuo’s first wife, Lady Xiangli, gave birth to two sons, and his second wife, Lady Yang, had three daughters, the second one being Wu. Wu disliked her two half-brothers because they had ill-treated her beloved mother. When Wu rose to power, she sent the two half-brothers to distant provincial posts, and both died in exile.3

Emperor Taizong, the second Tang Emperor, and his son, Li Zhi, were both attracted to Wu Zhao’s beauty, intelligence, and spirit. When she was fourteen, Taizong awarded her the title cairen (fifth-rank concubine). Taizong had a deep admiration for the girl’s spirit and intelligence. The emperor owned a very wild horse that no one could master and so asked his palace women for advice. Wu replied, “I can control him [the horse], but I shall need three things: first, an iron whip; second, an iron mace; and third, a dagger. If the iron whip does not bring him to obedience I will use the iron mace to beat his head, and if that does not do it I will use the dagger and cut his throat.”4 Taizong was pleased and employed Wu as his personal secretary for ten years. During this period, she gained experience working with official documents and learned the necessary useful skills for conducting state affairs. Despite an intimate relationship, Wu, probably because of the couple’s age gap, did not bear Taizong any children. Upon Taizong’s death in 649, in accordance with the tradition of royal families, all his consorts were to retire to temples, shave their heads, and become nuns to pray for his soul, living the rest of their lives in confinement.

Wu Zhao entered Ganye Temple and became a Buddhist nun. On the first anniversary of Taizong’s death, the successor to the throne, Emperor Gaozong, went to the temple to offer incense and met Wu, and they wept together for Taizong. Gaozong was astonished by her beauty when they had first met in the Imperial court and since his father’s death paid regular visits to the temple in hopes of encountering the widow. Wu knew well the character and weaknesses of this young emperor. She tried to provoke him into taking her back to the Imperial court by saying, “Even though you are the Son of Heaven, you can’t do anything about it [referring to the fact that she was confined in the temple].” Gaozong quickly responded: “Oh, can’t I? I can do anything I wish.” Wu Zhao emerged at the right time.5 Empress Wang had recently lost the favor of Gaozong because she bore him no children. Gaozong turned to his concubine Xiao, who did bear him a son and two daughters. Empress Wang, trying to distract Gaozong’s attention from Xiao, encouraged Wu to secretly stop shaving her head. She was soon invited back to the Imperial court and given the title zhaoyi (second-rank concubine) of Gaozong.

The title zhaoyi did not satisfy Wu’s ambition. Her next step was to eliminate Empress Wang and concubine Xiao. Wu played her game well because she knew that it was imperative for her to be the mother of royal sons. She bore Gaozong four boys: Li Hong in 652, Li Xian in 653, another Li Xian in 655, and Li Dan in 662. In addition to winning the emperor’s favor, Wu pleased the empress and Imperial court servants through the strategy of winning their trust by her friendliness and generosity. Court attendants were willing to report to her even the most trivial court occurrences. Empress Wang was fond of children, and Wu’s newborn daughter provided Wu an opportunity to eliminate the empress. Shortly after Empress Wang had played with the baby, Wu killed her own infant daughter and blamed the murder on Empress Wang. Gaozong believed this and soon dismissed his empress and promoted Wu Zhao to the position; she immediately put Wang and Xiao to death and exiled their relatives and supporters.

Empress Wu was now able to fulfill her long-cherished Imperial dream and grasped all power in the guise of assisting Gaozong in managing state affairs. Gaozong was afraid of Wu because of her high intelligence and skills in manipulating officials. When Gaozong made Li Hong the crown prince in 656, Wu’s power continued to grow as the mother of a young future emperor. She established an informer system and appointed cruel officials to remove any opposition to her authority. These officials employed extensive torture, and many high ministers and aristocrats suffered from Wu’s repression of enemies or potential opponents. Wu also made great efforts to dispose of political rivals, having them removed from office, exiled, and executed. Zhangsun Wuji, one of her leading political opponents, was forced to commit suicide in 659. The next year, Gaozong suffered a severe stroke that blinded him and assigned all state affairs to Empress Wu. Wu was the virtual ruler of the empire for the next twenty-three years.

Gaozong died in 683. Since Wu’s eldest son had died even earlier, her second son, Li Xian, ascended the throne as Emperor Zhongzong (r. 684). Within a year, she had replaced him with her youngest son, Li Dan, who assumed the title Emperor Ruizong (r. 684–690), but like his father after the stroke, he was a puppet emperor. During this period, Tang loyalists and Tang princes fomented several revolts, but Wu proved to be competent in quelling them. By 690, she had eliminated almost all her political rivals. Wu was displeased that her long record of successful administration stimulated any revolts, so she decided to ignore all conventions and become an emperor. In 690, she conferred upon herself the title “Holy and Divine Emperor,” founded what she called the “Zhou dynasty” (not to be confused with the ancient Zhou Dynasties), and named Luoyang as the capital. She ruled for the next fifteen years as the only woman emperor in Chinese history, until she was finally deposed in a coup shortly before her death in 705. Some historians correctly argue that Wu was ambitious, cunning, and ruthless, but her major achievements, which helped bring prosperity to Tang China, are difficult to overestimate.

Wu pleased the empress and Imperial court servants through the strategy of winning their trust by her friendliness and generosity. Court attendants were willing to report to her even the most trivial court occurrences.

Major Achievements

The first achievement was Wu Zhao’s policy of recruiting officials. The basic criteria of selection of officialdom shifted from personal integrity or conduct to a greater emphasis on candidates’ education levels and intellectual capabilities. By implementing this change, Wu broadened eligibility for the bureaucracy by placing more emphasis on recruiting talented and educated aristocrats, scholars, and military leaders than limiting high officials to a few powerful aristocratic clans. This may have been the reason she avoided any mutiny that threatened her regime. In 693, Wu wrote the two-volume Rules for Officials and made it part of the examination curriculum, replacing the old Daoist classic, Daode Jing. She even initiated the personal examination of candidates by the ruler because she believed this system could best serve her objective of effective Imperial management. The civil service examination was not new in Tang China, but Wu’s reforms would serve as a foundation for later dynasties developing an even stronger examination system.

The second achievement was Wu’s policy of maintaining China’s Imperial sovereignty, expanding Tang territories through conquering several regions, and exercising a dominant cultural influence over Japan and Korea. Despite armed clashes with neighboring Tibet, Wu, through a combination of military force and diplomacy, managed this, as well as other foreign threats to Imperial China.

The third achievement was Wu’s policy of economic development. Agriculture caught the attention of Wu, who ordered the compilation of farming textbooks, construction of irrigation systems, reduction of taxes, and other agrarian reform measures. In 695, for example, Wu offered the entire empire a tax-free year. Despite this, her tax office still benefited from trade opportunities through the Silk Roads between China, Central Asia, and the West. Her economic policies apparently improved the life of peasants, moving them toward prosperity and peace. Some historians argue that Wu lived in extravagance in later years because of showy Buddhist monasteries built to satisfy her private needs. However, in the eyes of the common people, she may have been an incredibly popular ruler. Evidence from a stele in Sichuan Province shows that, in time of flood or drought, people pray at a temple in the name of “Celestial Empress.” She is still honored today by an annual agricultural festival there, especially on her birthday.

After she gained power, Wu Zhao helped spread and consolidate Buddhism and supported the religion by erecting temples so priests could explain Buddhist texts.

The fourth achievement was Wu’s patronage of Buddhism. As a child, Wu was introduced to Buddhism by her parents, and, as noted earlier, she was briefly a Buddhist nun. After she gained power, Wu helped spread and consolidate Buddhism and supported the religion by erecting temples so priests could explain Buddhist texts. She thought highly of Huayan Buddhism, which regarded Vairocana Buddha as the center of the world, very similar to Wu’s desire to become the holy emperor. Wu’s Buddhist sect also encouraged its followers to regard their earthly ruler as the representative of Vairocana Buddha, a belief that Wu probably regarded quite favorably as Empress. Wu assumed herself a reborn Buddha and a descendent of the ancient Zhou kings. In 692, she issued an edict forbidding the butchery of pigs. In the eyes of Chinese Buddhists, Wu may have been a popular ruler. Her patronage of Buddhism paved the way for its spread during the reign of Emperor Ruizong, when voluminous Buddhist texts were translated, edited, and published.

The fifth achievement was Wu’s promotion of literature and art. She was a poetess and artist. Little is written in English concerning the artistic life of Wu, for scholars have put much weight on her ambitious political life. In Wu’s childhood, she had the opportunity to learn history, literature, poetry, and music. During her reign, she formed a group, “Scholars of the Northern Gate,” for the promotion of the associates’ literary pursuits. Both Emperor Gaozong and Wu were fond of literature and poems, and helped create a culture of literary pursuits that flourished in Tang China. Some prominent Tang poets such as Li Bai (701–762) and Du Fu (712–770) appeared after the death of Wu. Even many Tang courtesans were great singers and poetesses.

The final achievement was Wu’s support of women’s rights. She began a series of campaigns to uplift the position of women. She advised scholars to write and edit biographies of exemplary women to assist in the attainment of her political objectives. Wu asserted that the ideal ruler was one who ruled as a mother does over her children. Wu also extended the mourning period for a deceased mother to equal that of a deceased father and raised the position of her mother’s clan by offering her relatives high official posts. She may have thought that princesses were conducive to reconciling diplomatic conflicts, since she formed marriage alliances to aid her expansionist foreign policy.

Many Confucian scholars probably viewed Wu’s behavior as scandalous, immoral, and outrageous. Her gravestone was unmarked by any eulogy; it was deliberately left blank upon her request. She expected people of later periods to evaluate her achievements.

Conclusion

Historical evaluations of Wu are mixed. The most favorable assessments highlight her high intelligence and exceptional competence in many areas of governance. As briefly discussed earlier, the biggest critics of Wu focus upon her ambitious character and ruthless actions to gain and keep power. At least in China, it appears based on content in recent history textbooks that Wu is viewed more favorably than in the past. In the 1950s, history textbooks put no weight on Wu’s position in Chinese history because the Mao Era (1949–1976) emphasized a socialist revolution led by the masses rather than by “feudal rulers.” However, textbook author evaluations of Wu tended to be milder in the 1980s, the time when the policy of opening up to the outside world began, thus broadening people’s perspectives. In the 1990s, when Chinese patriarchy displayed a clear increase in tolerance for women, Wu Zhao was praised as China’s “only ruling empress” in history textbooks. By the twenty-first century, instead of minimizing Wu’s political achievements and extensively emphasizing her personal actions and ruthlessness, in various renditions of Wu there is more of a tendency to emphasize her successes in governance and her place in Tang China’s “Golden Age.” This tendency runs counter to the Confucian cultural tradition of minimizing female political accomplishments.6

A further legacy of Wu was women’s participation in politics. She was a vivid example; later, Princess Taiping (her daughter) and Empress Wei (her daughter-in-law) became involved in Imperial politics as well.

Controversies and shifting interpretations of her life notwithstanding, Wu did leave some legacies to Chinese history. Most notably, she substantially improved the civil service system and Imperial talent pool, initiated policies that strengthened the Tang economy, lowered taxes, apparently improved the life of common people, and protected China’s borders while maintaining Imperial prestige. These successes made it easier for successors, particularly Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756). Tang China scholar Charles Benn regards Xuanzong’s reign as the “Golden Age,” which was the longest, the most glorious, and the most prosperous epoch of the Tang Dynasty, and a period when the arts flourished.7

A further legacy of Wu was women’s participation in politics. She was a vivid example; later, Princess Taiping (her daughter) and Empress Wei (her daughter-in-law) became involved in Imperial politics as well. Empress Wei perhaps had pretensions of emulating Wu. In 710, she murdered her husband by poisoning him and then engineered a coup hoping to rule after him. However, her planned takeover failed and Empress Wei was executed. Princess Taiping, though wielding great power at the Imperial court, did no better in attempting to follow in her mother’s footsteps. In 713, she plotted to overthrow Emperor Xuanzong, but the Emperor and his loyalists discovered the coup and killed Princess Taiping. At least some women leaders in twentieth-century China looked on Wu as a model. Song Qingling (1893–1981), the wife of Sun Yatsen, regarded Wu as an effective political leader. Song was politically active in 1950s China and in 1981 was awarded the title Honorary President of the People’s Republic of China. Jiang Qing (1914–1991), the wife of Mao Zedong, identified with Wu. She may have tried to use the example of Wu as part of a propaganda campaign to claim herself the successor to Mao, but she eventually failed.

Wu also made her way into literary works. The fantasy/feminist Qing Dynasty novel Flowers in the Mirror by Li Ruzhen (1763–1830) takes place during Wu’s rule. The fictional Wu issued twelve decrees that were intended to bring benefits to women. Although the decrees are fictional, Wu’s life perhaps inspired Li and later authors who were pioneers of the emancipation of women in Qing China. Historian of Chinese women’s culture Dorothy Ko has observed that some women gentry in Qing China were far from oppressed or silenced and were well-known poetesses, singers, editors, and teachers who formed their own community networks.8

Wu Zhao possibly influenced attitudes about sexuality and women; her reputation for sexual promiscuity occurred during a relatively permissive period of Chinese history. Tang China allowed women some latitude regarding remarriage and sex. However, attitudes changed considerably after the Song period (960–1279). The influential Song philosopher Zhu Xi (1130–1200) formulated the concept of separate spheres and reemphasized the importance of women’s chastity. He believed that it was better for a woman to starve than be unchaste. Zhu was aware of Wu and her scandals, of course, and thought that the reign of Wu was unlawful; a woman’s proper place was at home. As Zhu was the founder of neo-Confucianism, his views on women’s chastity had a far-reaching impact on later scholars. Some Song historians used the case of Wu’s scandals in their writings about chaste women. The chastity cult survived to Qing China, but in present-day China, Wu receives a more favorable image than before, as Chinese patriarchy has increased its tolerance toward women.

Even though Wu died over 1,300 years ago, she remains a well-known figure in China’s past and controversy still surrounds her. She has been the subject of a series of historical television drama in contemporary China, notably Hunan’s 2014–2015 dramatic series on Wumeiniang chuanqi (The Legend of the Charming Lady Wu or The Empress of China). The drama appealed to a vast audience as well as provoking state censorship, not just because of its extravagant budget and boldness in production, but also its scandalous depiction of the actress Fan Bingbing in the role of Wu and audience’s attitudes about sexuality and women. The drama first aired on commercial satellite station Hunan Television on December 21, 2014, but was canceled a week later because of government censors’ objections and resumed broadcasting on January 1, 2015, with almost all the breasts and cleavage of actresses cropped out. Some television viewers are furious about state censorship because the edited drama has lost its aesthetic values and is not historically accurate. Perhaps there is always a tension between the ruling class and people in their perceptions about sexuality and women, whether in Tang and Song China or in present times. At any rate, Wu Zhao remains an important historical figure from China’s Imperial period.

NOTES

1. Samuel Adrian M. Adshead, China in World History, 3rd ed. (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000), 54.

2. N. Harry Rothschild, “Wu Zhao’s Remarkable Aviary,” Southeast Review of Asian Studies 27 (2005), 1.

3. Denis Twitchett and Howard J. Wechsler, “Kao-tsung (Reign 649–83) and the Empress Wu: The Inheritor and the Usurper,” in Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank, eds., The Cambridge History of China, vol. 3, reprint of 1979 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 246; Dora Shu-fang Dien, Empress Wu Zetian in Fiction and in History: Female Defiance in Confucian China (New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2003), 37; Jonathan Clements, Wu: The Chinese Empress Who Schemed, Seduced and Murdered Her Way to Become a Living God (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 2007), xv.

4. Translation adopted from Charles P. Fitzgerald, The Empress Wu, 2nd ed. (London: Cresset Press, 1968), 4.

5. Conversation adopted from Yutang Lin, Lady Wu: A True Story (London: Heinemann, 1957), 17. Also see Rothschild, “Wu Zhao’s Remarkable Aviary,” 1; Rothschild, “Wu Zhao and the Queen Mother of the West,” Journal of Daoist Studies 3 (2010): 30–31.

6. Nan Guo, “Analysis of the Image of Wu Zetian in Junior Middle School Teaching Materials,” Chinese Education and Society 36, no. 3 (2003): 34–36, 39–41; Xianlin Song, “Re-gendering Chinese History: Zhao Mei’s Emperor Wu Zetian,” East Asia 27 (2010): 376–378.

7. Charles D. Benn, Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2002), 7–8.

8. Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1994), cover page.