In 1909, the Korean An Chunggŭn (1879–1910) killed Itō Hirobumi, a high-ranking Japanese official responsible for the expansion of his country’s power into the Korean peninsula. An examination of An’s life and why he killed Itō can tell us much about why some Koreans chose to violently resist Japan’s growing empire. Moreover, this examination will reveal the connection between religion, politics, and the spread of modern knowledge in Korea.1

Background

An was born in 1879, only three years after Korea was “opened” to the outside world. It was in fact Japan that forced Korea to accept a modern—and unequal—treaty in 1876. Korea’s entry into the age of imperialism led to conflict on the peninsula, as China, Japan, and later Russia competed for influence over the country while various Korean political factions, each with a different vision of reform and each looking to a different foreign country for aid, struggled for power. Japan eventually came out on top, winning wars against China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–05), and sent Itō Hirobumi, a senior statesman, to Korea as Resident-General in 1906 to cement Japan’s power in the country. Itō used this position to push through what he believed were necessary modernizing reforms, causing many Koreans, including An, to fear for the complete loss of their country’s independence.

The Young An Chunggŭn

An was born in northern Korea into a family of country gentry. While his father was a scholar, the young An preferred roaming the mountains with hunters to his studies.2 When An’s classmates taunted him for his lack of knowledge, An proclaimed that he wanted to become like Xiang Yu, the mighty general who would later become king in China’s Warring States period (232–202 BC); and to achieve this goal, he need only be able to write his name. An was given a chance to fulfill his martial dreams following the 1894 Tonghak Rebellion. The uprising would eventually spread to the north, leading An’s father to form a militia as rebellious peasants threatened wealthy landowners such as himself. An, then sixteen years old, led a daring assault on the Tonghak forces, which, thanks to the timely intervention of his father, headed to the routing of the Tonghak and the capture of their rice, weapons, and horses with no losses to the militia. An claimed that this great victory was “the will of Heaven.” However, after the battle, two powerful Korean officials claimed that the rice T’aehun had seized from the Tonghak belonged to them, and he was therefore liable for it. Unable to withstand their pressure, T’aehun fled to the Catholic cathedral in Seoul, where he received sanctuary from French missionaries. He eventually converted to Catholicism and, with the protection of foreign missionaries, returned home with a Korean catechist (a Catholic teacher from the Korean population) who proceeded to convert most of the An family and their village. While An obediently converted to Catholicism at his father’s request and was baptized, he noted in his autobiography that he came to believe firmly in his new faith.

An Chunggŭn’s Political Awakening

Through his new religion, An became quite close to Father Wilhelm, a member of a French religious order who spoke Korean well and from whom he learned much about the outside world and the danger Korea faced. The connection of faith and country can be seen in An’s concern, which he expressed to Wilhelm, that the ignorance of Korean Catholics hurt both their church and their country and that the Catholic church should establish a university in Korea to rectify that situation. Wilhelm agreed, but their bishop did not, fearful that education would make Catholics indifferent to their faith. Despite this rejection, An still received important advice from Catholic priests. For instance, An’s fear about the future of Korea first became acute when Wilhelm told him that no matter who won the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War, Korea’s fate would be the same—to be dominated by the victor. It was at this point that An, the hunter who had only wanted to know enough to be able to write his name, began to read avidly in order to understand what was happening and what he could do. Similarly, after Japan’s victory and the forcing of the Korean court to accept a treaty that took away much of its sovereignty, An concluded that he should flee to China, a move made by other Korean nationalists, and work for the cause of Korean independence there. However, a French priest he knew convinced him that doing so would be a mistake. Referring to Alsace and Lorraine, the cleric stated,

As you know, our country lost two provinces in a war with Germany.3 We had several opportunities over the last forty years to recover them but the public-minded people had fled those regions to foreign countries. Because of that, we still haven’t been able to reunite with them.

This convinced An to stay in Korea.

For An, concerns over increasing Japanese power on Korea were not just abstract fears. Back in his homeland, An took part in a movement that sought to pay back the money Korea owed Japan so that the loan could not be used to further whittle away at Korea’s sovereignty. However, a Japanese policeman came to a meeting of the association and insulted Korea, leading to a fistfight between him and An. Similarly, An invested in a coal mine in hopes of developing Korea’s national economy, but because of “Japanese obstruction,” he lost his money. Although An had more luck with education— he helped establish and administer a night school that taught English and an elementary school—such activities would take time to bear fruit. And with increasing Japanese pressure, as seen by the disbanding of the Korean military, the forced abdication of the Korean emperor, and the signing of a new treaty that took away even more of Korea’s already-reduced sovereignty, all of which happened under Itō Hirobumi’s charge in 1907, time was something that Korea lacked.

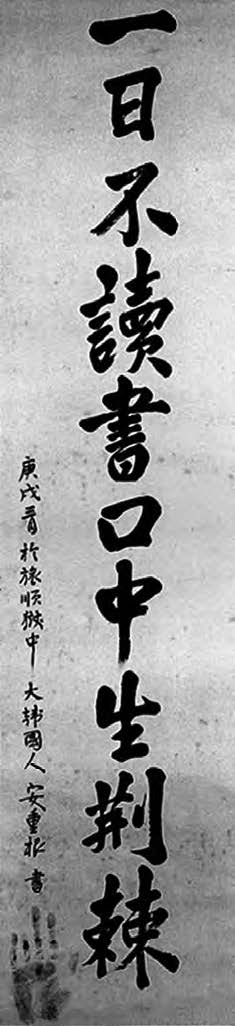

In response to Korea’s deteriorating situation, An sought out and joined a Korean guerilla army operating in Manchuria, where he served as an officer. After leading his soldiers to one victory in Korea, his army was destroyed. Surviving a harrowing journey back to Manchuria, An became convinced that God had saved his life so he could perform some “great deed.” He therefore took it as a “heaven-sent” opportunity when he learned that Itō, retired from his post as Resident-General but still active in Japanese politics, would be traveling through Manchuria. An intercepted Itō at the railway station in Harbin and shot him minutes after he disembarked from the train, fatally wounding the statesman. An then shouted, “Hurrah for Korea” and was arrested.

Why Itō?

An answer to the question of why An ChunggŬn killed Itō can be found in an excerpt from the transcript of the fifth session of An’s trial, held on February 12, 1910:

The Japanese emperor’s declaration of war at the beginning of Japan’s conflict with Russia stated that [Japan was fighting] to maintain peace in the East and to strengthen Korean independence. Many Koreans believed those words and hoped to stand alongside Japan in the East. However, because Prince Itō’s policy was opposed to this, Righteous Armies rose up everywhere . . . They continued to fight the Japanese and the country is still in turmoil. About 10,000 Koreans have been killed. It was their intention to sacrifice all they had for their country. And because of Prince Itō they have been slaughtered . . . and he has endangered the world with his evil and cruel butchery. Not a few officers and men of the Righteous Armies have been killed in battle . . . I think that if that policy is not reformed, Korea will not be safe and the war between Korea and Japan will continue indefinitely. Prince Itō is no hero. He is a villain of great cunning. He claimed that Korea was becoming more civilized [under his protection] and had the newspapers publish articles tricking the Japanese government and emperor into believing that his control over the country was increasing . . . As for me killing Prince Itō, as long as he remained, the peace in the East would be disturbed and relations between Japan and Kor ea would be strained. Therefore, in the capacity of a Righteous Army officer, I executed him. I hope that relations between Korea and Japan will become closer and peace in the East will reign as an example to the rest of the world.4

As seen from this passage, An believed that Itō was pursuing a policy that had already killed many Koreans and promised to kill many more. In an unfinished essay titled “A Treatise on Peace in the East,” An wrote further on that subject, explaining how Japan’s policy not only harmed Korea, but would lead to a massive war in East Asia that would kill millions.5 Because, according to An, Itō had tricked the Japanese emperor and public into believing that Koreans supported the protectorate, killing him would show them that Koreans opposed the protectorate, thereby convincing the Japanese emperor to change Japan’s policy in Korea to one that would help Korea modernize while maintaining its independence, consequently bringing peace to East Asia. Unfortunately for An, he did not realize that the Japanese emperor and public in fact supported Japan’s colonial project in Korea. An was consequently found guilty of murder by a Japanese court and executed on March 26, 1910, only months before Japan annexed Korea.

An Chunggŭn and World History

The story of An illustrates how deeply connected the world was by the early twentieth century; how far-reaching Western (and to a certain extent, Japanese) influence had become; and how missionaries served as an important transmission point for new knowledge, both religious and political. Through his Catholic faith and contact with missionaries, An, who knew no languages other than Korean and classical Chinese, had come to some knowledge of Western ideologies and world politics, helping to make the killing of Itō thinkable. Moreover, An’s explanations of why he killed Itō provide us greater insight into why Koreans were willing to violently oppose the Japanese empire, when in historical hindsight, such resistance seems futile. For An, whose views were likely similar to those of many other Koreans, a limited understanding of Japanese politics, his belief in divine intervention, and his sense of urgency that something had to be done to not only protect his nation but to prevent a war that would kill countless people made violence appear not only legitimate, but an effective means of ending the violence that surrounded him.

NOTES

1. For a longer summary of An’s life and the assassination of Itō, see Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912 (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2002). See also Franklin Rausch, “Visions of Violence, Dreams of Peace: Religion, Race, and Nation in An Chunggŭn’s A Treatise on Peace in the East,” Acta Koreana 15, no. 2 (December 2012): 263–91.

2. The authoritative version of An’s autobiography (An Ŭngch’il yŏksa/The History of An Ŭngch’il) can be found in Yun Pyong Suk [Yun Pyŏngsŏk], ed. and trans., An Chunggŭn chŏn’gi chŏnjip [The Collected Autobiographies of An Chunggŭn] (Seoul: Kukka Pohunch’ŏ, 1999).

3. These provinces lay between France and Germany and were claimed by both countries. France lost them in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). They are now a part of France today.

4. For the official government records of the trial, see Sin Unyong, trans., An Chunggŭn∙Wu Tŏksun∙Cho Tosŏn∙Yu Tongha kongp’an kirok: An Chunggŭn sakkŏn kongp’an kirok sinmun kirok [The Trial Records of An Chunggŭn, Wu Tŏksun, Cho Tosŏn, Yu Tongha: the Trial Records of the An Chunggŭn Incident] (Seoul: Ch’aeryun, 2010).

5. This essay can be found in Yun Pyong Suk [Yun Pyŏngsŏk], ed. and trans., An Chunggŭn chŏn’gi chŏnjip [The Collected Autobiographies of An Chunggŭn] (Seoul: Kukka Pohunch’ŏ, 1999). An English-language version translated by Jieun Han and Franklin Rausch can be found in Asia 6, no. 1 (2011): 48–75. These sources were translated into English by Franklin Rausch and Jieun Han.