In an age of unprecedented Sino-American contact, cooperation, and competition, it is hard to believe that a scant four decades ago, our two peoples barely knew one another. In February 1972, President Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao Zedong held a summit that laid the foundation for the Sino-American relationship as we know it. Perhaps you have seen the images before: the president and First Lady Pat Nixon fronting a large entourage on the Great Wall; a frail, though still sharp, Mao wearing an impish grin while shaking hands with a clearly delighted Nixon and Premier Zhou Enlai and Nixon toasting one another with kind words and shots of maotai in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People. But how significant was the 1972 Nixon-Mao summit, and why should a twenty-first-century student learn about it?

Simply put, the summit was one of the major diplomatic turning points in modern history. It was a watershed moment that ended years of Sino- American animosity and opened two of the world’s largest, most influential nations to a variety of new opportunities. Although Nixon and Mao did not establish full diplomatic relations, they did oversee a dramatic revival of trade, travel, and exchanges in education, science, sports, and culture. They also paved the way for their successors, Deng Xiaoping and President Jimmy Carter, to overcome the two nations’ remaining differences and restore full relations in 1979 (a process known as “normalization”). Finally, the summit is worthy of our attention because it has always been controversial. Both Nixon and Mao angered some of their closest allies by hobnobbing with the “enemy,” and now-declassified summit records show that Nixon was willing to sacrifice much for short-term political gain. Moreover, the major source of Sino-American disagreement in 1972—Taiwan—remains a sticking point to this very day.

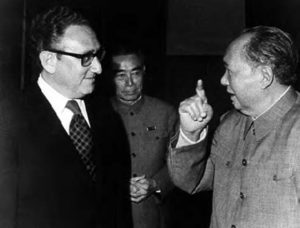

The summit thus stands as a fitting point of embarkation when teaching the modern Sino-American relationship and related subjects, like superpower relations, the American presidency, the Việt Nam War, Chinese internal politics, and China’s “opening up” to the world. In a way, this is very much a story of Cold War diplomacy and the national interests of the Americans, the Chinese, and the Russians. But it continues to fascinate be- cause it is a tale of intriguing personalities—a commingling of cultures and a clash of egos between its four chief participants: Nixon, Mao, Zhou, and Henry Kissinger.

The Capricious Sino-American Relationship

In order to understand the significance of the 1972 summit, we must turn the clock back a bit further. Ideological differences and Cold War geopolitics fostered a hostile Sino-American relationship between the end of the Chinese Civil War (1927–1949) and the early 1970s. The civil war pitted the Republic of China’s (ROC) nationalist government against an insurgency led by the Communist Party of China (CPC). The United States, which was then a far more inward-oriented society than it is today, stayed out of this struggle for more than a decade, but Washington did offer some economic assistance to the ROC and its leader, Chiang Kai-shek (Jiăng Jièshí), in their fight against Japan. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawai`i, in De- cember 1941 pushed the US and ROC into a formal alliance and spurred a dramatic increase in aid, though Americans in China soon realized that the nationalist government suffered from mismanagement, corruption, and military inefficiency.

Relations between the US and the PRC were doomed from the start. Each side rejected the other’s ideology, and many Chinese were angry that the US had so strongly supported the nationalists.

At the war’s end, Americans found that they could not simply follow their longstanding tradition of postwar military retrenchment and a rapid mustering out of the troops. Not only did the civil war in China resume, but the US and Britain were occupying Japan and southern Korea, and the Soviet Union was jockeying for regional influence. By 1947, the Cold War was fully underway, and American foreign policy was increasingly geared toward one overarching goal: halting the spread of Communism. Influential Americans—the so-called “China lobby”—soon realized that their erst- while wartime ally, the ROC, was in dire straits. Although Washington policymakers expressed misgivings about supporting the relatively weak nationalist government, they were willing to grant the ROC more than a billion dollars from 1945 to 1949 to fend off a Communist victory. Despite these grants, the People’s Liberation Army defeated the nationalists; Mao Zedong declared the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949; and Chiang Kai-shek’s government and two million Chinese citizens fled to Taiwan.

Relations between the US and the PRC were doomed from the start. Each side rejected the other’s ideology, and many Chinese were angry that the US had so strongly supported the nationalists. The Korean War (1950–53) made matters worse. American and PRC troops faced each other on the field of battle for nearly three years, during which the US lost 37,000 troops and the PRC lost between 150,000 and 400,000. The war not only solidified Sino-American enmity, but it also tilted the US toward full support of Taiwan and an expanded regional defense posture.

As Washington and Beijing eyed each other suspiciously for the next two decades, the US followed a two-tiered China policy. First, Washington sought to weaken and marginalize the Beijing regime by severing diplomatic relations, cutting trade and travel, denying it multilateral recognition, and organizing an allied trade embargo. Second, the US strengthened its regional partnerships by stationing thousands of troops and creating military alliances with Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and several nations in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Sino-American tensions occasionally increased, as when the PRC attempted to seize or shell disputed islands in the Taiwan Strait. Hostilities also escalated when the PRC tested its first nuclear weapon and ramped up its financial and manpower support to North Việt Nam. As the US war effort in Việt Nam escalated in the ‘60s, Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution drove the PRC further into isolation.

Yet, by the decade’s end, the geopolitical environment had changed so dramatically that observers noted a thaw in tensions between the US, the USSR, and the nations of Europe. This thaw grew, in part, from divisions in the Communist and non-Communist camps. A decade-long ideological conflict between the PRC and the Soviet Union—the Sino-Soviet split— reached its apex in March 1969, when the two nations actually got into a shooting war in the Ussuri River border region. In Europe, meanwhile, the Communist nations of Yugoslavia, Albania, and Romania were no longer in the Soviet orbit, and the “Prague Spring” reform era in Czechoslovakia was crushed in 1968 by a Moscow-directed Warsaw Pact invasion. The Western nations had also grown apart. The US could not convince its NATO partners to participate in the Việt Nam War. France not only pursued a more unilateral course, but it even withdrew from NATO’s integrated military command and ejected all foreign troops from its soil. At the end of the 1960s, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt began to cultivate close ties with East Germany and the USSR in a process called Ostpolitik, and soon thereafter, President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev forged a working relationship known as “détente.” But despite this decrease in East-West tensions, it was not clear that Mao’s China would participate in these developments.

The Road to the Summit

Richard Nixon and his closest foreign policy confidant, National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, certainly hoped to foster an opening with Beijing. As foreign policy pragmatists, these two men were willing to deal with all governments, even undemocratic ones. As early as 1967, private-citizen Nixon had broached an opening to China in the journal Foreign Affairs. “Taking the long view,” he wrote, “we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates, and threaten its neighbors.”1 During his first year as president, his ad- ministration sent out more signals. Not only did he reiterate his interest in a working relationship with China, but he also eased travel and trade restrictions and ordered the US Seventh Fleet to stop its patrols in the Taiwan Strait. Although the US and PRC had no formal relations, they could communicate through “back-channel” methods, such as sending messages through other governments. Thus, Nixon used Pakistan, Romania, and Poland to send word to Beijing that his administration wanted to talk. Beijing agreed to resume bilateral talks, and Chinese and American representatives began conferring in War- saw in January 1970. These talks ended abruptly when Nixon expanded the Việt Nam War into Cambodia.

Mao sent his own signals later that year. He invited the American journalist Edgar Snow—an old acquaintance from the 1930s—to Tiananmen Square to be photographed with him on National Day, October 1, 1970. Premier Zhou Enlai then sent a note to Nixon via the government of Pakistan, stating that China “has always been willing and has always tried to negotiate by peaceful means A special envoy of President Nixon’s will be most welcome.” Henry Kissinger later wrote that this message was “clearly an event of importance. This was not an indirect subtle signal to be disavowed.”2 Nixon rose to the bait and publicly stated that the most important challenge of the decade was drawing the PRC into a constructive relationship with the global community. Although the US would not accept the PRC’s ideology or abandon Taiwan, he asserted, a rapprochement was in both nations’ interests. Soon thereafter, the US lifted its last travel restrictions.

At this point, Mao chose an unusual way to begin the rapprochement in earnest. In spring 1971, the US table tennis team happened to be playing at the world championship tournament in Japan. When a chance en- counter brought together members of the Chinese and American teams, one of the Americans expressed an interest in traveling to China. Shortly thereafter, the PRC surprised the team with a formal invitation. When they visited in April 1971, they were treated as honored guests. Zhou Enlai even hosted them in the Great Hall of the People and promised to send a Chinese team to the US. Three months after this episode, which the press dubbed “ping-pong diplomacy,” Kissinger made a secret trip to Beijing and in the process became the first American official to visit China in over two decades. Nixon then announced that he would be traveling there early in 1972. “We have laid the groundwork for you and Mao to turn a page in history,” wrote Kissinger to Nixon.3

Another turning point took place three months hence, when a United Nations resolution expelled the ROC/Taiwan government from the General Assembly and Security Council and officially replaced it with the People’s Republic. The US had helped defeat over a dozen such resolutions in two decades, but it was unable to block or rephrase this one. Yet despite the US government’s public position against ousting Taiwan, in reality, Nixon considered Taiwan an irritant on the path to a rapprochement with the PRC. Kissinger had already made it clear to Beijing that the US would not stand by Taiwan forever, and he had confided to Nixon that although America’s break with Taiwan was “a tragedy,” the administration nevertheless “[had] to be cold about it.” Nixon concurred: “We have to do what’s best for us.”4

What did Beijing and Washington want in a rapprochement, and why? Nixon had three primary motives. First, he wanted Chinese help in ending the Việt Nam War on terms that were good for America. Second, he hoped that a rapprochement with China would give him some leverage in his dealings with the Soviet Union. Third, he wanted to boost his chances of winning re-election by showing the American public that he was a great statesman who was capable of bold diplomatic strokes. Al- though he was much younger than Mao, he had an electoral timeline to consider. “I approached this trip as if it were the last chance I would have to do some- thing about the Sino-American relationship,” he wrote in his memoir.5 Henry Kissinger had his own goals. As a former university professor holding an unelected position, he had no political pedigree and no true constituency. Because many Americans questioned his central policymaking role, he reasoned that a successful China opening would grant him the status of a great diplomat. He would also get a trump card in dealings with his primary overseas concern, the USSR. Nixon and Kissinger had no real interest in trade since the PRC was then a poor nation with little to export.

Mao chose an unusual way to begin the rapprochement in earnest.

Mao, too, had multiple motives. On foreign pol- icy matters, the Chinese leadership was divided be- tween Zhou Enlai’s moderates, who wanted closer relations with the US, and Lin Biao’s faction, which preferred closer ties to the USSR. Mao tilted toward Zhou in 1970, in part be- cause he feared that Lin was becoming too powerful. Mao also wanted advanced aviation and military technology, and he needed a strong partner in his conflicts with the Soviet Union and India. He was particularly interested in having the Americans place advanced nuclear weapons on Chinese soil. Mao’s ego may also have played a role in his calculations: After several years of national isolation and the controversies of the Cultural Revolution, he may have hoped to reacquire international prominence.

When Nixon arrived in Beijing on February 21, 1972, Zhou met him on the tarmac. Remembering that former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had refused to acknowledge Zhou in 1954, Nixon pointedly stuck out his hand in greeting. Zhou told Nixon during the drive into the city, “Your handshake came over the vastest ocean in the world—twenty-five years of no communication.” Because Mao was in poor health, the itinerary did not include a Nixon-Mao visit. But upon Nixon’s arrival, Mao got a burst of energy and summoned the president to his residence at Zhongnanhai in central Beijing. When the Nixon-Mao meeting finally took place, the irony was overwhelming. Here was the world’s foremost anti-Communist unashamedly sitting down in the Spartan quarters of the world’s foremost Communist leader. During their sixty-five minute conversation, Mao was clearly the man in charge. “I have met no one,” Kissinger later wrote, “who so distilled raw, concentrated willpower.” Nixon and Kissinger politely flattered Mao, whereas Mao offered only faint praise to his guests. When Nixon told Mao, “The chairman’s writings moved a nation and have changed the world,” Mao gave the president a slight compliment: “Your book, Six Crises, is not a bad book.” And when Nixon raised specific national and regional is- sues, Mao insisted that he would only discuss “philosophical” questions.6 As it happened, this was their only face-to-face meeting during the eight-day summit. The rest of Nixon’s visit was taken up with negotiations with Zhou Enlai, lavish banquets, cultural events, and a bit of tourism.

Mao and Zhou had already learned that the Americans were willing to offer a lot without expecting much in return. When Kissinger had first come to Beijing seven months earlier, he had promised that Nixon would push for normalization of relations and Chinese entry into the United Nations. Kissinger had also promised to deliver intelligence on the USSR, and he had discussed a timeline for a withdrawal of US troops from Việt Nam. With these issues out of the way, the future of Taiwan remained a sticking point at the Nixon-Mao summit. In the post-summit joint communiqué, the PRC claimed to be “the sole legal government of China” and argued that Taiwan’s “liberation” was “China’s internal affair.” Meanwhile, the US called for a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question but also acknowledged that “there is but one China” and that “Taiwan is a part of China.” Despite the Taiwan problem, Nixon hoped that the public would remember the symbolism more than the policies: “Let us . . . start a long march together,” he stated in a banquet toast, “not in lockstep, but on different roads leading to the same goal, the goal of building a world structure of peace and justice.” Shortly before returning to America, he, rather hyperbolically, called his trip “the week that changed the world.” 7

Although some American observers were cautious about the summit’s results, most applauded Nixon. James Reston of The New York Times, who was otherwise consistently critical of the president, wrote that Nixon

has shown foresight, courage, and negotiating skill. He has changed his direction, his policy, and the tone of his diplomacy, and there are few people in [Washington] today who don’t welcome the change.

But many conservatives were angry, as were some European and Asian allies. The government of Taiwan was livid over the apparent abandonment. South Korean President Park Chung-hee declared a state of emergency and stated, “Only we, the Koreans who have had personal experience, can tell how terrible the Asian Communist menace is.” Conservative commentator William F. Buckley said that watching Nixon toast his hosts in Beijing “was as if Sir Hartley Shawcross had suddenly risen from the prosecutor’s stand at Nuremberg and descended to embrace Goering and Goebbels.”8 Mao, too, faced his allies’ criticism for eschewing revolutionary Communist ideology and siding in- stead with traditional balance-of-power diplomacy. North Vietnamese leaders were angry that he was trading with the enemy, while Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha sent him a sharp letter demanding more Chinese aid. The Soviet press assailed China’s “anti-Sovietism” and Nixon’s “television diplomacy.”

What Did It All Mean?

Given the evolution of the Sino-American relationship and China’s remarkable economic growth since 1972, it seems axiomatic that the Nixon-Mao summit was extremely important. To be sure, a few immediate results are beyond dispute. The Beijing regime ended its self-imposed isolation while also receiving much-needed respect and a new, powerful partner. Nixon came home to a hero’s welcome and won re- election in a landslide eight months later. The summit also increased the standing of Kissinger and Zhou Enlai. Bilateral trade quickly surpassed economists’ predictions, and Mao was able to secure some new technology, including Boeing aircraft and RCA earth satellite ground stations. “Liaison offices” were opened in each capitol to serve as de facto embassies, and Beijing invited a series of congressional delegations to China. Then there was the summit’s considerable psychological impact. As one Mao biographer has written, “a nagging obsession that China and the US had felt about each other lifted like a weight from each side’s shoulders.”9

Although the 1972 breakthrough is generally considered to have been good for both countries, perhaps we should not overestimate its importance. In the short term, only a handful of Chinese elites and a few Western politicians and businessmen benefited from the contacts and exchanges. Former policy advisor William Bundy even asserted that a US- China rapprochement was inevitable, irrespective of Nixon’s leadership. Kissinger essentially agreed, later writing that an attempt at rapprochement would have been made “no matter who governed in either country.” He also insisted, without a hint of irony, that he and Nixon developed the opening with “smoothness and speed,” using “subtlety and single-mindedness.”10 The Chinese contributed little to the Việt Nam peace talks that eventually brought about the 1973 peace accords, and the Watergate investigations prevented Nixon from expanding the relationship with Beijing. Without his strong leadership, the normalization process floundered. After he resigned in August 1974, his replacement, Gerald Ford, worked to maintain the fragile détente with the Soviet Union but largely neglected the Sino-American relationship. Factional struggles among the aging PRC leadership were yet another impediment to normalization.

In the final analysis of the 1972 summit’s significance, it seems appropriate to link it with three additional defining moments in recent Chinese history: the 1976 passing of Mao Zedong, the accession of the far less dogmatic Deng Xiaoping, and the achievement of full Sino-American relations on January 1, 1979. Following Mao’s death, the new leaders in Beijing and Washington were more willing to transcend their differences and build a mutually beneficial relationship. Soon, the two countries were actually engaging in military cooperation, and the staunchly anti-Communist President Ronald Reagan was not only visiting Beijing, but also touting Chinese productivity and the two nations’ joint capitalist ventures. Most significant of all were Deng’s economic reforms, which turned China into a global powerhouse and a major American trading partner. Every one of these outcomes was all but unimaginable before the Nixon-Mao summit.

NOTES

- Richard Nixon, “Asia after Vietnam,” Foreign Affairs 46, 1 (October 1967): 121.

- Henry Kissinger, White House Years (Boston: Little, Brown, 1979),

- Richard Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (New York: Grosset & Dun- lap, 1978), 554.

- Electronic Briefing Book 145, National Security Archive, document 5, Telcon, April 14, 1971, accessed July 11, 2012, http://bit.ly/Su9RwF; Margaret MacMillan, Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World (New York: Random House, 2007),

- Nixon, RN,

- Nixon, RN, 559–64; Kissinger, White House Years, 1056–1060; Robert Dallek, Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007), 364; Jung Chang and John Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2005), 584.

- Memcon, document 139, Foreign Relations of the United States 1969–1976, July 9, 1971, http://1.usa.gov/PAKK4S; Joint Statement, February 27, 1972, Public Papers of the Presidents, http://bit.ly/RfO6Mp; Toasts of the President and Premier Zhou Enlai, February 21, 1972, http://bit.ly/VAlQIb.

- James Reston, “Mr. Nixon’s Finest Hour,” New York Times, March 1, 1972, 39; Chong- Sik Lee, “The Impact of the Sino-American Détente on Korea,” Sino-American Dé- tente and Its Policy Implications, Gene T. Hsiao (New York: Praeger, 1974), 198; Linda Bridges and John R. Coyne, Strictly Right: William F. Buckley, Jr. and the Amer- ican Conservative Movement (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2007), 142.

- Ross Terrill, Mao: A Biography (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), 354,

- Chang and Halliday, Mao, 586–87; MacMillan, Nixon and Mao, 337–338; William Bundy, A Tangled Web: The Making of Foreign Policy in the Nixon Presidency (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 244; Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995),