The purpose of this essay is to assist readers in understanding the government-sponsored Chinese sports system, which for over sixty years has altered its use of sport based upon ideological and/or policy objectives. Since the Communist 1949 takeover, the government has in subsequent decades utilized sports to further socialist goals, train elite athletes for Olympic glory, and as an international projection of soft power. China might be about to experience an ideological paradigm shift regarding the role of sports in culture that could alter how many ordinary Chinese perceive sports. Due in part to successful economic reforms that have created a burgeoning middle class, many Chinese see sport as a leisure activity with additional health and recreation benefits. This new public interaction with sports in China is setting the stage for the government sports industry to open up to further innovation and development projects that appeal to the wide range of individual preferences.

The Mao Zedong Era and the Birth of Elite Sports

During Mao’s rule in China from 1949 to 1976, sports were first seen as a militarized and socialist movement in which all citizens were required to take part. Policy dictated that mass participation in physical activity was an essential part of the culture, and necessary for a strong and healthy working class. Training one’s body was part of the daily regimen and served as both a political and cultural objective. Mao felt it was imperative to build people’s health in order to maintain and defend the nation. Sports inspired a collective work effort that united the country in the spirit of socialism. To fulfill this political ideology, a disciplined physical education program was implemented for the purpose of preserving the collective Chinese body. Mao’s physical education program included callisthenic exercises that were practiced by virtually everyone, including soldiers and party officials, every morning and afternoon in workplaces and educational institutions. In Mao’s estimation, physical training was as important as moral education and intellectual development, with the latter processes significantly influenced by physical training. Without physical development, there was no basis for moral and intellectual education.1 Mao asserted that physical education was to serve the political purpose of building a class of citizens who were well-disciplined in both mind and body.

While this was a time when most of the population participated in physical education for moral and intellectual improvement, the Mao Era also introduced an elite sports system that has dominated the cultural and political identity of sports in the nation for the past forty years. At the same time Mao was incorporating socialist ideology into China’s daily routines, the 1952 Olympics were being held in Helsinki, Finland, and it was the first time in which the Soviet Union competed in the games. The

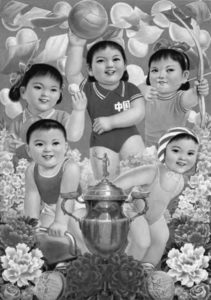

children taking part in basketball, ping-pong, archery, bicycling, and swimming, with 1984 gold medals on the sides of the trophy in the foreground. Source: Chineseposters.net at http://tinyurl.com/hotbkew.

Soviet delegation was hugely successful. These games served as an eye-opener to China’s political leaders and provided the Communist Party an example of how a socialist country could defeat Western democratic countries on the international stage. Shortly after, it was proposed the Chinese learn from the Soviet model to develop acentralized system of sports predicated upon projecting its political strength, ideologies, and diplomatic requirements onto the international stage. What followed in China was the introduction of a powerful centralized and hierarchical state organization of elite sports learned from the Soviets that would recruit and train professional athletes. This system, however, would not truly take off until after the Cultural Revolution, the termination of Mao’s reign, and the end of China’s relative political and economic isolation from the global community.

Ping-Pong Diplomacy and the Lasting Legacy of an Elite Sports System

Because of Cold War controversies over the “Two Chinas Question,” the Helsinki games would be the last time China participated in the Summer Olympics until the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. China’s economic climate had begun to change after Mao’s 1976 death, and Deng Xiaoping, who was more open to the world than Mao, piloted policies of foreign engagement and much more foreign access to China. However, even before Mao’s death and the beginning of Deng’s rule, it was sports that helped reopen China to international involvement. In 1971, the American pingpong team received an invitation from China to visit. This was the first time an American delegation had set foot in China since the Communist Party took control in 1949. Later termed “Ping-Pong Diplomacy,” this event helped pave the way for US President Richard Nixon’s 1972 historic visit to China.

China’s leadership realized that sports could be an important political tool in another respect: it could reshape the country’s substantial negative international image. It was a way for the Chinese to show the world through successes in international competitions that China was ready to emerge from the shadow of the Cultural Revolution and into the global spotlight. In a short period of time, the primary objective of sports in China shifted away from a collective program to maintain its citizens’ moral and intellectual health to an individualistic pursuit where only the most advanced and elite athletes were encouraged by the government to extensively participate.

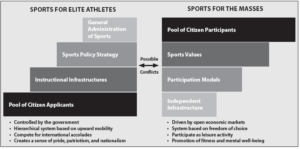

This became even more apparent as Deng ushered in economic reforms that would use a substantial private sector to modernize the nation and increase international trade. As Deng implemented his economic reforms, the government tightened its control over sports and began to use athletics to project national vibrancy on the international stage. Deng believed that success in international competition would lead to international recognition, and his sports policy emphasized building a positive image abroad. Under the economic reforms, competition was believed to “promote activism” by eliminating the apathy produced by a system that equally rewarded freeloaders and hard workers. Competition was to be the “source of vitality” in the reforms.2 The central government hoped success in sports would stimulate the international community to recognize China’s newfound strength, give ordinary Chinese a nationalistic rallying cry, and cultivate more domestic support for the political leadership. The Chinese government consolidated funding for sports under the General Administration of Sport (GAOS), which is responsible for policymaking and administrating the All-China Sports Federation and the Chinese Olympic Committee. GAOS created a centralized system of provincial sports bureaus and management centers across the nation. Beijing’s primary concern was to produce elite athletes for selection into the national and Olympic teams. Every training center had the ultimate goal of Olympic gold medals, glory for the nation, and the projection of power to the international community.

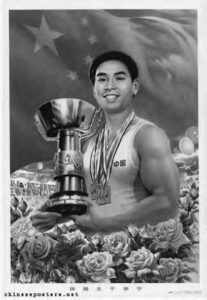

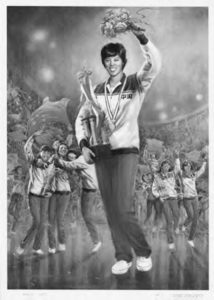

This system of elite sports has constituted national government sports policy for the past thirty years. The 1984 Los Angeles Olympics resulted in China’s first-ever gold medal winner, Xu Haifeng, in the men’s free pistol competition. Also, gymnast Li Ning, China’s most prolific athlete of that era, won six medals in Los Angeles: three gold, two silver, and one bronze. The Chinese women’s volleyball team also earned acclaim and a gold medal in the 1984 games by defeating the USA in the title match.

That year, the 353-person delegation from China took home fifteen gold, eight silver, and nine bronze medals, finishing fourth in the overall medals tally. From that point forward, the development of sports in China was geared toward the Olympics. The best and the most talented athletes were identified early, and put through a rigorous method of training in hope of creating athletes prepared to succeed at the highest level of international competitions.

The 1984 Olympics, Market Economics, and Chinese Sports

As China’s economic reforms continued to reshape the nation, many Chinese persisted in their Olympic fever and relished the successes of Chinese athletes in international competitions. But the 1984 Olympics had a much greater and lasting effect on Chinese society than just creating a forum for nationalistic pride and patriotism. The Los Angeles games were the first time the Olympics had truly been commercialized. Sponsorships from large multinational corporations deluged the games with advertisements and brought real economic profits to the Olympics for the first time in its history. The commercialization of the Olympics incentivized China’s political leaders to note the possible financial gains sports might create. It was a propitious time for China to infuse its state sports system with capitalism and stimulated the movement to host the Olympics on home soil. Internationally known expert on Chinese sports Susan Brownell wrote:

Clearly, there was a complicated, mutually implicating relationship between China and the Los Angeles Olympics that merits further analysis . . . [a] poorly studied aspect of the relationship: the impact of the Los Angeles Olympics on China’s other reform—the

economic reform. Indeed, this legacy is more important than the diplomatic legacy, because it went beyond economic reform in a narrow sense, and connected with the larger cultural and social transitions that accompanied it—the transitions that drove China’s ascent to the position of the world’s second-largest economy in the two and a half decades after Los Angeles.3

As China continued to ramp up its efforts to train elite athletes for Olympic glory, the government began to imbue sports with the same types of market reforms that were sweeping across the countryside. While elite athletes were still under state control, they were becoming professionalized and afforded freedoms atypical of the rest of Chinese society, and more in line with professional athletes from Western countries and Japan. This laid the groundwork for subsequent expansion of the supply of Chinese Olympic level-athletes.

Source: Xinhua on ChinaDaily.com.cn at http://tinyurl.com/zu6r4n7.

The continual buildup of the Olympic sports model that emphasized winning gold medals continued and arguably intensified. In 2001, Beijing was awarded the right to host the 2008 games, creating significant excitement and anticipation for a grand opening of China to the international community. The games were to be an event like no other, a historical and cultural display of the country. Chinese leaders were well-aware that during the Olympics the nation’s social and political environment would be subject to an intense level of international inspection. The Beijing Olympics did in fact garner scrutiny and humanitarian tension over China’s foreign policy in Sudan and Tibet. However, much to the delight of the Chinese government and its citizens, the Olympics indeed showcased China’s athletic progress. The international community saw China’s political, economic, and social growth both on the playing field and throughout the county. Some of China’s most recognizable athletes, who trained in the government system, were showcased to the world and with them brought pride, glory, and gold medals to the host nation. The most notable of the government-supported athletes to compete in the 2008 Olympics was basketball superstar Yao Ming, who also famously had to broker a deal with the Chinese government in order to play in the NBA. In the 2008 games, China’s athletes took home fifty-one gold medals, more than any other country, as well as 100 total medals, and surpassed international expectations in what the host country could offer athletically. In this respect, China triumphed.

The 2008 Beijing Olympics did almost exactly the same for China as the 1984 Los Angeles Games did for the United States, which was to cement its sports system as a commercialized entity and an economically driven enterprise. The hosting of the games dramatically impacted the development of the sports industry in China. Investment in the sporting infrastructure leading up to the Beijing Olympics created an environment ripe for an emerging sports market. While some might minimize the connection between Olympic gold and a generally increased participation in sports, it appears that Chinese interest in sports has increased because of the Olympics, and citizens are consuming sports at a rapidly growing pace. Even though elite-level sports seem to be firmly under the control of the Chinese government, increased general participation rates indicate China is on the cusp of generating many more fine athletes than the state-selected few. Chinese scholar of sports Jie Zhang perhaps best assesses the contemporary importance of sports in China for consumers, the government, and the private sector providers:

As the world economy continues to develop and material living standards continue to increase, the consumption of sport has become an important element of expenditure in the pursuit of cultural needs. The sports industry has gained more and more attention from the state, society, and the public, and has increasingly been seen as a “sunrise industry” of the twenty-first century.4

Some of the most significant alterations in the sports industry occurred with the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) and the Chinese Super League (CSL). While both are restricted by government-relegated policies, these leagues operate, for the most part, under the auspices of Western commercialization, marketing, and management techniques. The leagues maintain strong relationships to government-sponsored programs and athletes, but welcome foreign players and coaches to team rosters. In addition, the leagues and teams utilize commercial sponsorships and private owners to help fund and support daily operations rather than relying on government subsidies. Leagues such as the CBA and CSL mark a changing of the guard in Chinese sports and show how far the industry has come by indoctrinating Western ideals into its cultural landscape.

The time and opportunity have arrived in China to create new development systems of sports that once again reach the mass population. Increased economic freedom has affected a significant segment of the Chinese population who are looking for ways to add sports into their daily routines. This is leading to the boom of the sports industry and a collaborative effort by entrepreneurs and consumers alike to find ways that sports speak to the individualist needs of the Chinese citizen.

The Future of Sports Development in China: Innovation, Opportunity, and Sport-for-All

As China’s citizens and its economic enterprises explore new opportunities in the twenty-first centuy, the development of sports is sure to become a landmark arena for innovation, growth, and drevelopment. China’s sporting culture has closely followed the political climate and changing economy of the country. Since the 1949 Communist rise to power, sports have been utilized to theoretically improve the people’s intellectual and moral development. Then, the government cultivated a select group of elite athletes to project China’s soft diplomacy within the international community. Now, as the next wave of sports development occurs in China, it is sure to focus on both the elite sports system and opportunities for its citizens in general, invigorated by the success of its international superstars but just as much by private entrepreneurs and consumer demand for more sports. China is set to host the Winter Olympics in 2022, and this will undoubtedly encourage the Chinese government to pursue the same buildup of elite winter sports athletes seen prior to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. The government will continue to invest time, money, and resources to build up not only the winter sports infrastructure but also the elite athletes it hopes to showcase on home soil during these games. This will be a difficult undertaking, considering the current lack of facilities and skilled winter sports athletes. However, the Chinese government has more than five years leading up to this event and has surely begun preparations to display to the world a culture of individual opportunity and health. 2008 was a showoff year. 2022 will be another, only this time in winter sports competitions.

Although the government remains firmly entrenched in the development of elite athletes, it also recognizes the potential growth opportunities in marketing sport to its massive population of more than 1.3 billion people. Indeed, in 2011, State Councilor Liu Yandong repeated the words of Hu Jintao, the General Secretary of the CCP: “Coordinated development of both elite sports and mass sports should be achieved to further transform China from a major sports country to a world sport power.”5

So the twenty-first century should mean the expansion of sporting opportunities for the average Chinese citizen. Economic reforms have brought about a bourgeoning middle class in China and a multitude of citizens who have become consumers of Western values, including our sportcentric attitudes. Our Western enthusiasm for sports is beginning to invigorate Chinese society in the fields of health, recreation, tourism, and leisure activities. Each of these areas has a place for sports to insert itself into China’s future economic development. Chinese citizens now have a place for more autonomy, choice, and free will in their decision-making; so too may their sports industry become increasingly individualized. More elite athletes will follow the example of professional tennis player Li Na, who broke away from the government system to control the path of her career and capitalize on her marketability. But the biggest change will take place in developing programs and sporting initiatives that appeal to the general population’s personal preferences. Health and fitness clubs for the public are beginning to pop up in the country. So too are natural landscapes becoming more available for camping and hiking. Sport recreation leagues will appeal to the average citizens, regardless of skill level. The possibilities are endless. For as diverse as the Chinese population is in their interests, the development of sports in the country must broaden in order to appeal to all. One thing is for certain: Sports are no longer just for elite athletes. The industry must show innovation and ingenuity during this time of growth and expansion of sports in China.

NOTES 1. Howard G. Knuttgen, Qiwei Ma, Zhongyuan Wu, eds., Sport in China (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers Inc., 1990). 2. Susan Brownell, Training the Body for China, Sports in the Moral Order of the People’s Republic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995). 3. Susan Brownell, “Why 1984 Medalist Li Ning Lit the Flame at the Beijing 2008 Olympics: The Contribution of the Los Angeles Olympics to China’s Market Reforms,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 1 (2015): 128–143. 4. Jie Zhang, “Reality and Dilemma: The Development of China’s Sports Industry since the Implementation of the Reform and Opening Up Policy,” International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 8 (2015): 1085–1097. 5.Tien–Chin Tan, “The Transformation of China’s National Fitness Policy: From a Major Sports Country to a World Sports Power,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 8 (2015): 1071–1084.

MATTHEW BRYAN HAUGEN is a PhD student at the University of Illinois, UrbanaChampaign, in the Kinesiology Culture, Pedagogical, and Interpretive Studies program. His current research interest is sport development in China. Prior to starting the program at Illinois, he worked as the Head Tennis Coach in Hebei Province for the Chinese government Olympic development program. Haugen spent three years in China training elite athletes in the government system and traveled with his players throughout Asia to compete in domestic and international competitions. While in China, he completed his MEd in Education Curriculum and Instruction, Physical Education Pedagogy, from Boise State University. Haugen’s thesis topic focused on his time working as a foreign expert in the Chinese sport system.