I started teaching Japanese popular culture in the 1990s when there was an increased interest in Japan due to the country’s economic expansion in the US and the world. I taught it in person first and then shifted to online, using different textbooks, other learning materials and activities. In the essay that follows, I focus on the online format and explain what I teach and how I do it in detail to help others develop their courses. The same format can be used to teach the popular cultures of other Asian countries.

Overview of the Course

Whether I teach a course on Japan or the US, popular culture is defined as the daily cultural environment which includes beliefs and values, rituals, icons, heroes, stereotypes, traditions, religions, education, foodways, etc., too numerous to list all. It is different from pop culture which refers to popular entertainment forms, such as music, anime and manga, sports, and video games. Needless to say, pop culture is part of popular culture. Because my goal is to teach students how ordinary people experience their lives, the course description and Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs) for my Japanese popular culture course are as follows:

This course will introduce you to the major cultural environment in which a majority of Japanese people have lived during the past seventy years. We will examine the activities, objects, and entertainment forms Japanese people commonly encounter in their daily lives and consider the values and attitudes expressed in them. The course will consist of readings, lectures, discussions, and media presentations.

After taking this course, students will know:

• The influence of traditional religions on contemporary Japanese

society and culture.

• The socialization experience of Japanese people.

• The Japanese worldview.

After taking this course, students will appreciate

• A culture, including popular art and entertainment forms, different

from their own.

There were some concerns on my part about the focus of the course in the early days of teaching. I thought students would want to learn about Japanese pop culture and might get turned off by the focus on the cultural environment. My experience has taught me that a majority of students who take the course are already familiar with Japanese pop culture; they read manga, watch anime, play video games and listen to J-pop. They do not need to learn about them but want to know Japanese culture that has produced them. I have had students who actually started their own

exploration of history and aesthetics. Therefore, the focus of the course actually meets their interest and they enjoy learning about the daily life of Japanese. In contrast, a challenge I have experienced is how to teach the daily cultural experience of Japanese people to students in southwestern Ohio and northern Kentucky who have limited opportunities to encounter Japanese people, let alone visit Japan. Published teaching resources are of little help. Textbooks and AV resources on Japanese culture are readily available but they mostly cover traditional (high) culture, such as noh theater, tea ceremony, and calligraphy, which are not necessarily part of the daily cultural environment of contemporary Japanese. Books on popular culture, on the other hand, focus on pop culture which is only one aspect of the contemporary Japanese experience.

I had used different textbooks, book chapters, and journal articles and tried to teach by using theatrical films but none of them had been satisfactory until I found A Geek in Japan: Discovering the Land of Manga, Anime, Zen, and the Tea Ceremony by chance during my random Amazon search.1 The author Hector Garcia, who has lived and worked in Japan since 2004, writes about his experience and observations of life in Japan. While there are a few questionable observations and spelling errors, the author covers concepts and aspects of Japanese daily life, which are hard to find in other books, ranging from concepts like amae and nemawashi to architecture. An additional strength is its abundant use of photos. I am a firm believer in seeing is believing/learning.2 Other valuable resources which improved my course tremendously are the Begin Japanology and Japanology Plus videos produced by NHK World.3According to the NHK World website, these videos provide “fresh insights into Japan. Stories behind Japanese life and culture through the eyes of Peter Barakan, a forty five-year resident and watcher of Japan.” Just like the textbook, the videos are about Japanese society and culture as experienced by non-Japanese.

I had used different textbooks, book chapters, and journal articles and tried to teach by using theatrical films but none of them had been satisfactory until I found A Geek in Japan: Discovering the Land of Manga, Anime, Zen, and the Tea Ceremony by chance during my random Amazon search.1 The author Hector Garcia, who has lived and worked in Japan since 2004, writes about his experience and observations of life in Japan. While there are a few questionable observations and spelling errors, the author covers concepts and aspects of Japanese daily life, which are hard to find in other books, ranging from concepts like amae and nemawashi to architecture. An additional strength is its abundant use of photos. I am a firm believer in seeing is believing/learning.2 Other valuable resources which improved my course tremendously are the Begin Japanology and Japanology Plus videos produced by NHK World.3According to the NHK World website, these videos provide “fresh insights into Japan. Stories behind Japanese life and culture through the eyes of Peter Barakan, a forty five-year resident and watcher of Japan.” Just like the textbook, the videos are about Japanese society and culture as experienced by non-Japanese.

Each video is thirty minutes long and covers a wide range of topics from cherry blossoms to ramen. Some videos are edited down to 10 minutes and offered as Begin Japanology Mini along with a full version. Furthermore, the videos complement the textbook. For instance, there are several videos on the train systems—trains, bullet trains, subways—which can be used with the textbook discussion of these topics. A Geek in Japan and the Begin Japanology videos are the main sources of information for students which are supplemented by additional readings, videos, and websites as illustrated in the course modules structure and content pages. The information provided by the supplemental videos is accurate but generalized so that I add an explanation when it is appropriate. Students respond to the learning materials positively as represented by the comment on the course evaluation: “the learning was greatly enhanced by mixing textbook reading with

videos and additional articles.”

Course Modules

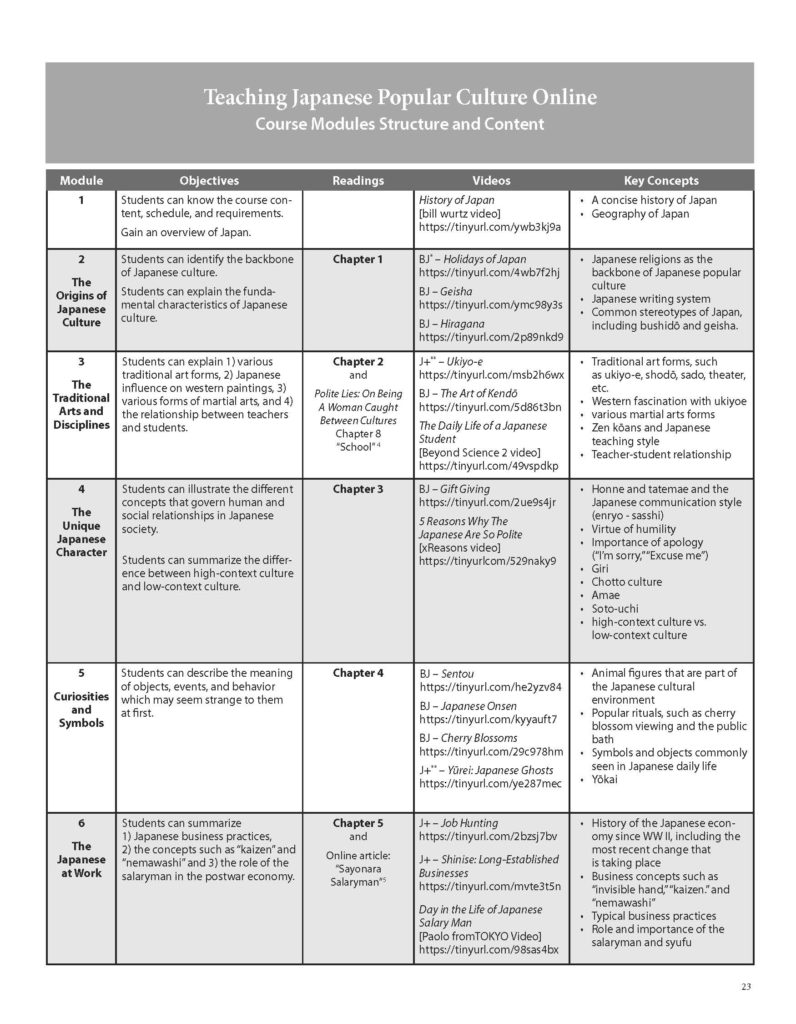

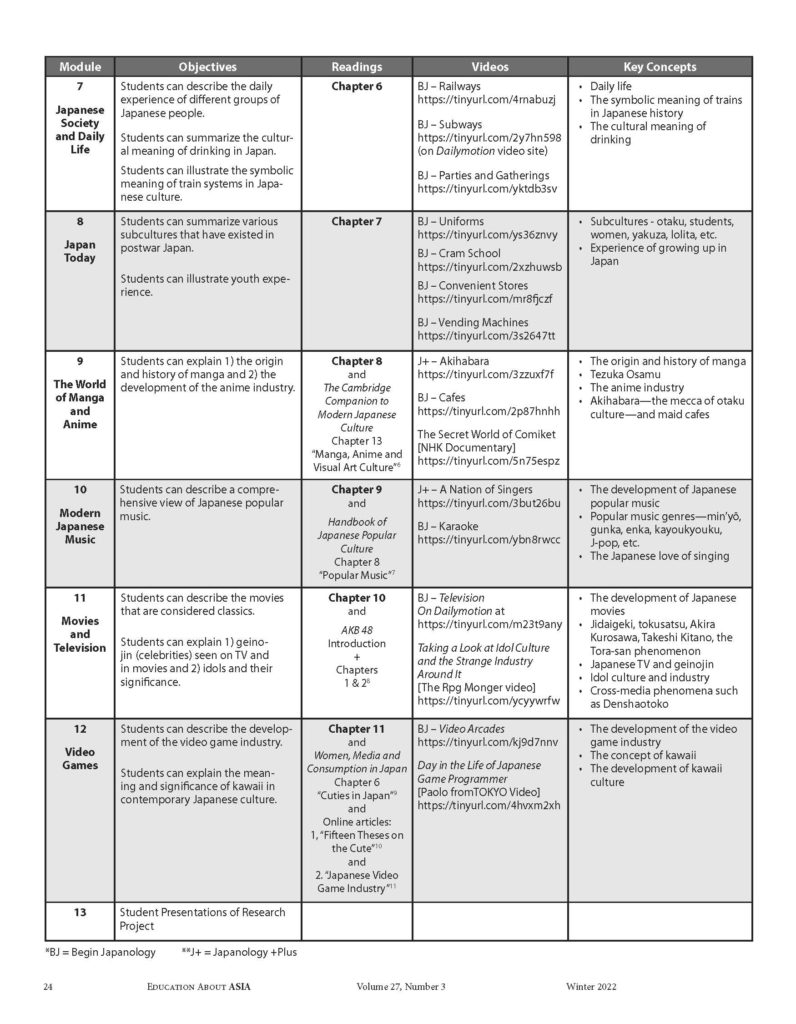

The course consists of thirteen modules each of which is based on a chapter in the book and two modules—the first and last weeks of the semester—which are reserved for the introduction to the course and student presentations. Between Module 2 and Module 12, the module titles correspond to those of the book chapters.

Learning Activities and Evaluation

I do not believe objective tests and quizzes are effective learning tools in this course and have used a variety of other methods to enhance students’ understanding of Japanese popular culture. For instance, instead of memorizing the national holidays, students are asked to discuss the perception of religions among the Japanese by responding to the scenario in an essay exam. As new pedagogical approaches that focus upon student engagement and active learning were introduced in the last decade, the following methods have proven to be effective for my classes.

Student-led Discussion Board

For each learning module, two to three students are appointed as discussion leaders. Each leader is responsible for posting two discussion questions by Wednesday each week and other students respond to the questions for the rest of the week.12 This creates a livelier discussion because, when I pose a question, it tends to be more difficult and some students do not respond well. Students feel more comfortable with answering the questions posted by their peers as attested to by a student’s comment on the course evaluation: “She was good at not expressing her opinion but getting us to examine our own opinions.” Another advantage of student-led discussion is that I can find out students’ perspectives on the topic which gives me a teachable moment. For instance, many students said that they were too shy to sing in front of strangers and this gave me a chance to discuss the function of karaoke in Japanese society as well as to remind them of the concept of amae

which we had studied earlier. Even if a person does not sing well, others will forgive him/her. Generally, I do not intervene in a discussion but I do jump in to supply information that facilitates further discussion.

Module Reflection

Every week students are asked to briefly describe two takeaways and one question about the module material. This provides me with another opportunity to know students’ perspectives and interests as well as the effectiveness of the teaching material because, interestingly, the takeaways and questions tend to focus on one or two topics which are covered in the module. For instance, many students did not understand the high suicide rate among the Japanese which was mentioned in the textbook and this became another teachable moment to introduce the concept of the face which was influential in Japanese culture. After reviewing all reflections, I give feedback to the whole class usually by sending an email and sometimes by adding additional learning materials to the module. I also answer the questions individually, thus building rapport with students. Students like the feedback as attested by the following comments on the course evaluations: She gave excellent feedback to our written reflections and questions. The instructor had wonderful supplementary materials and would often give more information or corrections through email. Her feedback was also meaningful and timely.

Student Feedback

In addition to those which were cited above, below are some of the comments I received on the course evaluations in the spring semester of 2020. Along with Japanese popular culture, the instructor had a very good understanding of American popular culture so she was able to help us compare and contrast. Many of the Japanese concepts were very difficult to grasp from a western perspective but she did a great job relating them to something we could understand or had experience with. While there were no quizzes, it allowed me to study to learn instead of studying to succeed. The content was interesting, kept me engaged. Posted relevant and interesting resources.

Of these comments, the first two are instructive to those of us who teach a foreign culture. We should use students’ prior knowledge, i.e., their own culture, to teach a new culture. This makes it relatable to students. I frequently use examples from American culture always with the disclaimer that “I am not saying Japanese culture is better than American culture or vice versa. . . .” This statement is important in order to achieve the last SLO: “students will appreciate a culture, including popular art and entertainment forms, different from their own.” I hope this article provides helpful information to teach Japanese popular culture online. I want to reemphasize that the same format can be easily adapted to teach popular culture of another country. For instance, Tuttle Publishing has the A Geek in series on China, Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia and I am certain that books that cover the daily life of people in other countries are also available. As to the videos, I would recommend exploring international broadcasting services like NHK World and Arirang TV which offer cultural programs in English or with English subtitles. Needless to say, YouTube offers a variety of videos. So, good luck with developing your popular culture course. Feel free to contact me.

Selected Bibliography

Books and Articles Included in Modules

- Fujie, Linda. “Japanese Popular Music.” In Handbook of Japanese Popular Culture, edited by Richard Gid Powers and Hidetoshi Kato and Bruce Stronach, 197–219. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1989.

- Galbraith, Patrick W., and Jason G. Karlin. AKB 48. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

- Garcia, Hector. A Geek in Japan: Discovering the Land of Manga, Anime, Zen, and the Tea Ceremony, revised and exapnded edition. Clarendon, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2019.

- Kinsella, Sharone. “Cuties in Japan.” In Women, Media and Consumption in Japan, edited by Brian Moeran and Lise Skov, 220–254. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1995.

- Koizumi, Mariko. “Japanese Video Game Industry: History of Its Growth and Current State.” In Transnational Contexts of Development History, Sociality, and Society of Play, edited by S. Austin Lee and Alexis Pulos, 13–64. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Mori, Kyoko. Polite Lies: On Being A Woman Caught Between Cultures. New York, Ballantine Books, 1999.

- Norris, Craig. “Manga, Anime and Visual Art Culture.” In The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture, edited by Yoshio Sugimoto, 236–260. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Richard, Frances. “Fifteen Theses on the Cute” Cabinet 4, Fall 2001, https://tinyurl.com/43ku536u. Accessed June 10, 2022.

- “Sayonara Salaryman”. The Economist. January 3, 2008, https://tinyurl.com/5epa7at4. Accessed June 10, 2022.

Videos Included in Modules

- “History of Japan.” YouTube, “Bill Wurtz,” 2016. https://tinyurl.com/ywb3kj9a. An abbreviated history of Japan since 40,000 BC with entertaining graphics and narrative. The 9-minute video covers politics, economy, religion, and culture. It may not be appropriate for younger students due to a few vulgar words.

- “The Daily Life of a Japanese Student.” YouTube, “Beyond Science 2,” 2017. https://tinyurl.com/49vspdkp.

- “5 Reasons Why The Japanese Are So Polite.” YouTube, “xReasons,” 2016. https://tinyurl.com/529naky9.

- “Day in the Life of an Average Salaryman in Tokyo.” YouTube, “Paolo fromTOKYO,” 2019. https://tinyurl.com/98sas4bx.

- “The Secret World of Comiket.” YouTube, “Ms. Jeff,” 2016. https://tinyurl.com/5n75espz.

- “Taking a Look at Idol Culture and the Strange Industry Around It.” YouTube, “The Rpg Monger,” 2018. https://tinyurl.com/2s3eexek.

- “Day in the Life of a Japanese Game Programmer.” YouTube, “Paolo fromTOKYO,” 2019. https://tinyurl.com/4hvxm2xh.