One of the greatest challenges faced by teachers is identifying common ground on which we can meet to consider the different cultural expectations that separate us and the common human values that unite us. This essay suggests we can find such common ground by comparing content and literary techniques shared in three much-admired novels: The Life of an Amorous Woman (Koshoku Ichidai Onna) by Japanese poet and novelist Ihara Saikaku (1623–93), Moll Flanders by English essayist and novelist Daniel Defoe (1660–1731); and Memoirs of a Geisha by contemporary American novelist Arthur Golden. In these novels, the “temptress” or “fallen woman” heroine is less reviled for her sexual wantonness than admired for her ability to survive. Ideally, all students will read these three books in their entirety. Students who have read the complete texts will, of course, have a much greater opportunity to study style closely and address related thematic issues. However, the subject matter of these texts may create problems, especially in class discussions. To avoid battles with censors and bowdlerizers, I suggest that the teacher use excerpts, such as those identified by page numbers on a chart included in my brief lesson plan available at http://www.smith.edu/fcceas/traubwom.htm.

One of the greatest challenges faced by teachers is identifying common ground on which we can meet to consider the different cultural expectations that separate us and the common human values that unite us. This essay suggests we can find such common ground by comparing content and literary techniques shared in three much-admired novels: The Life of an Amorous Woman (Koshoku Ichidai Onna) by Japanese poet and novelist Ihara Saikaku (1623–93), Moll Flanders by English essayist and novelist Daniel Defoe (1660–1731); and Memoirs of a Geisha by contemporary American novelist Arthur Golden. In these novels, the “temptress” or “fallen woman” heroine is less reviled for her sexual wantonness than admired for her ability to survive. Ideally, all students will read these three books in their entirety. Students who have read the complete texts will, of course, have a much greater opportunity to study style closely and address related thematic issues. However, the subject matter of these texts may create problems, especially in class discussions. To avoid battles with censors and bowdlerizers, I suggest that the teacher use excerpts, such as those identified by page numbers on a chart included in my brief lesson plan available at http://www.smith.edu/fcceas/traubwom.htm.

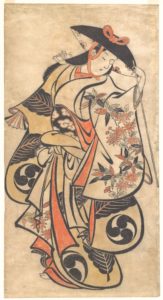

Above left photo: detail from the cover of Memoirs of a Geisha. Below left artwork: from Japanese Border Designs, Selected and Edited by Theodore Menten. Dover Publications, Inc.,1975

Recommended Versions of These Books

Most students find the work of Saikaku the least familiar. The Life of an Amorous Woman (1686) and Other Writings in the UNESCO Collection of Representative Literary Works, edited and translated by Ivan Morris (New York: New Directions, 1963), provides extensive background material, useful notes, and source materials. Although subject matter, language censorship, and personal comfort levels will force many teachers to extract representative passages from any of these texts, the substantial introductory essay in this edition is especially helpful in placing Saikaku within his cultural context and establishing parallels with his European contemporaries such as Moliere and Defoe. The Norton Critical Edition of Defoe’s Moll Flanders: An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism, edited by Edward Kelly (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1973), provides extensive background material and exhaustive lists of source materials. Even Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), on bestseller lists for almost three years and widely read by American students, requires careful previewing. The page numbers which follow quoted passages refer to this standard, widely available texts.

A Word of Caution

Teachers in secondary English and social studies classes and in lower division college and university English and theater courses may discount the subject matter of these novels as pornography at worst and romantic drivel at best, quibble at cultural misrepresentations, rage at historical inaccuracies, and cringe at the very idea that a privileged male author can assume with any degree of honesty the voice of a victimized female narrator. Such teachers are pressured to prepare students for high-stakes examinations, and instructional time is precious. At the same time, many teachers deeply and broadly trained in the subject matter of their discipline struggle to integrate well-respected contemporary literature into mandated course content. Although responsive to community mores, these teachers realize that the refusal to consider a text as widely popular as Golden’s novel is in itself a response to the novel. Steven Spielberg is threatening to make a blockbuster film (see “Spielberg’s Date with ‘Geisha’” by Daniel Frankel, http://aol.eonline.com/News/Items/0,1,2924,00.html). Madonna and The New York Times “Fashions of the Times” (Spring, 1999) agree wearing a kimono is the newest fashion statement. It is unlikely that scholarly reservations, no matter how valid, will prevent students from reading Memoirs of a Geisha.

Disengaged, nontraditional, nonspecialist, and occasionally unteachable, students are asking questions about Japan in social studies and language arts classes. The information they have and wish to augment, albeit distorted, fragmented, and sometimes downright inaccurate, can be used as a basis for a rigorous study of life in Japan. At the very least, pervasive student interest allows, even forces, serious teachers with little or no previous background to make Asian studies part of their curriculum. For that reason, it behooves us to consider how we can use this moment to open a broad-reaching, honest, appropriate discussion of common thematic content and literary techniques. Rather than focus on protecting students from objectionable content of such “dirty books” as Memoirs of a Geisha, perhaps we can seize a “teachable moment” and capitalize on the media hype surrounding this popular novel to introduce two great classics of the genre. By taking advantage of the surface interest in things Japanese, we can explore with students, who may never go beyond the glamorized film even so far as to read the novel on which the film is based, some interesting and relevant information about Japan as well as look deeply into the ambiguities raised when victimized female children survive.

Four centuries before Arthur Golden’s ravishing geisha arrived at the top of the best sellers lists—and stayed there— surplus female children received much the same education for a life of prostitution and struggled in the same way for economic viability and ultimately for physical survival. Long before Golden’s Sayuri as a middle-aged woman, traveled halfway around the world from Kyōto to New York to settle in Manhattan, Defoe’s Moll Flanders was leaving London to settle in Virginia and later on Maryland’s eastern shore.

Sayuri’s equally ravishing older sisters, Saikaku’s nameless amorous woman, and Defoe’s Moll Flanders survived to show up on every undergraduate’s reading list. In all three novels, the first-person narrator is introduced as a destitute female child, born in circumstances that force her into a life of dependency, at the mercy of men who expect to control her ability to survive. Despite the life she leads, each heroine survives into old age, becoming a prototype of a strong woman, the subject of examination questions, Ph.D. dissertations, and hugely popular movies. No scholar will deny that these texts, even with careful selection and editing, contain sensitive subject matter and raise issues that must be approached with care. However, Memoirs of a Geisha, Moll Flanders, and The Life of an Amorous Woman are riveting narratives appropriate for well-prepared secondary and university students in literature, women’s studies, and history classes.

Common Thematic Content

Similar economic imperatives haunt all three heroines despite the fact that they represent seventeenth-century Japan, eighteenth-century England and Colonial America, and twentieth-century Japan and the U.S. The nameless heroine in The Life of an Amorous Woman, which was published in 1686, notes, “To sell one’s body in this way is futile work indeed!” but suggests, “Such things, I may add, only happen to girls of poorer families” (134). Moll Flanders, who claims she was almost seventy when she wrote finis to her life story in 1683, notes simply, “Poverty is, I believe, the worst of all snares” (147). And things have not changed for Sayuri. The little girl who grows up to be Golden’s Geisha remembers, “. . . when my mother died, and I was cruelly sold, it was all like a stream that falls over rocky cliffs before it can reach the ocean” (428).

Print, 22 3/4 x12 3/4 in. Kaigetsudo, Anchi (Yasutomo), active 1700–16.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1949 (JP3106).

The reader is forced to note common cultural implications embedded in the education of girls, whether her training leads to becoming a household servant, a geisha, or a respectable man’s wife. Education received by the three female characters is painfully similar across cultures and times. For the amorous woman, training for the role of a concubine, which will allow her to “make one’s living in the world,” is explicitly dependent upon her knowledge about and access to beautiful fabrics (see pages 133–4). She is also aware that clothing makes the man and describes not only the clothing she needs to be successful but also the clothing she looks for in her customers, the “men for the up-to-date courtesan” (145–6). Moll Flanders also comes to realize that if she is to be a “gentlewoman,” either in the sense of being an economically independent upper-class potential wife or in the slang sense referring to a prostitute, she will be trained in the same sewing skills (9–16). Little Sayuri begins to grasp her plight when Auntie makes her realize the monetary value of the exquisite fabrics in the storehouse and the implications of being forced to damage a beautiful kimono. Auntie’s information leads to Sayuri’s aborted attempt to escape. Without access to beautiful fabrics and training, Sayuri would not become a geisha but, like her older sister Satsu, be enslaved as a prostitute (83–7).

Perhaps what is most interesting is that, as very young women, all three characters receive training that their societies recognize as specific to prostitution. Whether in the geisha school in Ky¬to (54–8) or the “little School” in Colchester, Essex (8–15), whether trained to dance in the Inoue School in the Gion (150–3) or required to make up an even number in country dances with the daughters of my “generous Mistress,” Sayuri and Moll receive much the same education.

At some point in the narrative, each woman survives by working in a textile-related occupation. The amorous woman describes how she makes a living sewing. She is very clear that, although as a seamstress, she is able to lead a “calm and virtuous life,” she misses male companionship (see pages 176–7). Within a short time, she spends all she has earned to buy the outfit she needs to attract male companions. These women not only create textiles but also buy and use textiles to make themselves beautiful and desirable, contributing to a circular economy of prostitution (202–3). By the time she is twelve, Moll Flanders has learned to sew and amuses the older woman with her naive wish to support herself with her needle (9). Later she becomes involved with pirates smuggling heavily taxed linen fabrics woven in the Netherlands. She marries a muslin and linen draper (51), and when distracted and raving, she finally takes to stealing; she steals fine fabrics (149–55). The twentieth-century geisha-in-training learns quickly that the most beautiful kimono will belong to the most economically secure geisha. She survives World War II by working for a kimono maker (see all of chapter 29, pages 345–51).

Despite their ability and willingness to work in conventional textile-related trades, for all three narrators, prostitution becomes the only alternative to starvation. Prostitution brings enormous physical danger, especially in relation to childbearing. The amorous woman admits to eight abortions and suffers both physical and psychic damage. In old age, she still recounts a haunting nightmare about her aborted children (192–4). Moll details the economics of surviving childbearing (126–33) with the same meticulous spreadsheet mentality that the amorous woman uses to keep track of her clothing expenses. Moll makes considerable efforts to place her babies in nurturing hands, and the success of her efforts to establish a relationship with her Virginia-born son by her brother-husband contributes to her happiness at the end of the narrative (260–5). Sayuri’s life is complicated when her mentor, Mameha, has a “medical appointment.” Mameha’s patron concedes, “We certainly can’t have any little barons running around, now can we?” (251–3). However, we understand that it is because Sayuri is the mother of the Chairman’s son that she is finally removed from Japan to New York, ending her life as a geisha and concluding the novel (434–6).

Woodcut, 21 x 11 in., attributed to Torii Kiyonobu

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1949 (JP3098).

All three characters receive similar education, struggle to avoid starvation, survive childbirth and, at the most desperate moment, resist suicide. The amorous woman is tempted to drown herself but becomes a Buddhist nun (207–8). At the end of the novel, she lives in seclusion, alive and telling her story to handsome young men who stumble on her hermitage. Moll cuts down her brother-husband when he attempts to hang himself (81–2). She flees physical and mental danger, and “perfectly Friendless and Helpless,” she chooses to commit the worst sin her value system seems capable of registering, that of stealing, rather than destroy herself (148). Cut off from everything she knows, terrified and enslaved, Sayuri risks her life and nearly kills herself in an attempt to escape the okiya to which she has been sold. When her attempt to free herself nearly kills her, she quite literally gets up and stays alive (93–8).

Common Literary Devices

As they become familiar with each narrative, students are surprised not only by the similar plights of the heroines but also by the similar literary devices the authors employ. They begin to look closely at the implications of male authorship in creating a female narrator. For example, we know exactly who wrote these novels, but the narrators these male authors construct raise all the historical and cultural questions associated with the legal status of women. Although claiming a good family, Saikaku’s heroine remains a nameless female even at the end of the novel. Perhaps the worst evil that engulfs Defoe’s heroine is the result of her namelessness, her inability to identify her blood relatives. In the first lines of the narrative, she tells the reader, “it is not to be expected I should set my Name, or the Account of my Family to this Work” (7). Her alias, Moll Flanders, identifies her not with her family blood ties but with the criminal economic activities by which she is able to survive. Like Golden’s Sayuri, she is given a professional name, and like Sayuri, she establishes herself within a family context as the mother of a son.

Interestingly, a close study of each novel as a prose text reveals that all three authors use similar literary devices to communicate similar thematic material. We find the same symbolic structures drawn from nature, such as seasons, weather, and vegetation; the same symbolic actions, such as writing; and the same symbolic objects, such as clothing and money.

If we accept the common interpretation of spring and dawn as symbolizing propitious new beginnings while night and moonlight symbolize calm, acceptable endings, the novels have interesting parallels. The Life of an Amorous Woman begins on a holiday morning in spring (121) and ends as the “moon of my heart is shining forth” (208). In Memoirs of a Geisha, the heroine foresees her adult life in a dreamlike experience beginning “Then in early spring” and ending with her acceptance of “What the future would be”(106–8). This passage is echoed in a similar passage at the end of the novel beginning “In the spring of the year” (422) and ending when the Chairman dies as “a leaf falls from a tree”(428).

All three novels are structured in a journey motif which begins as a physical journey and becomes a metaphorical journey into self-discovery and self-awareness. At the very beginning of The Life of an Amorous Woman, several young gentlemen are on a journey of discovery when they meet the amorous woman and stay to listen to her narrate her own journey through time and space from a beautiful young girl in service at the palace to an aged woman in a secluded hermitage (121). Moll Flanders journeys from Colchester to London and then as a bride (67–70) and later as a notorious thief (258–68) journeys from London to the New World of the American Colonies. Sayuri, sold by her father, journeys from her fishing village to Kyōto (32–7) and then, as a beautiful and famous geisha, journeys to New York City (423).

In all three novels, visual arts, including drawings, prints, and figure kimonos, represent ideal beauty or perfection. For the amorous woman, success in all things is possible because she matches in the flesh the perfect woman in a painting (132–3). Writing is even more powerful than images. Writing and calligraphy symbolize power, and words are magic. The amorous woman practices seduction by love letter (154–6) and is seduced by a picture sewn into a young man’s kimono (177–80). Moll Flanders and her true love express their feeling in poetry etched onto glass windowpanes (62–3). Sayuri’s life as a geisha is confirmed with a letter from Tanaka telling of her father’s death (102–3), her career is shaped by the inky calligraphy she is forced to brush across the images on Mameha’s beautiful kimono (72–3), and her fate is sealed when, outside the theater, the Chairman gives her his handkerchief with money in it (109–14).

These narrators perceive women in general and themselves in particular as objects. However, the object with which they equate themselves is different in each novel, and a close look at these objects and the functions which such objects serve in the cultures as described in the novels and in our own times as well, concludes a study of these wonderful texts. The nameless amorous woman tells her listeners, “A beautiful woman—so the ancients say—is an ax that cuts off a man’s very life” (121). To Moll Flanders, “When a Woman is thus left desolate and void of Council, she is just like a Bag of Money, or a Jewel drop on the Highway, which is a prey to the next Comer” (101). Sayuri, using images that combine art, especially writing, with the power of nature, claims at the end of the novel, “But now I know that our world is no more permanent than a wave rising on the ocean. Whatever our struggles and triumphs, however, we may suffer them, all too soon they bleed into a wash, just like watery ink on paper”(428). Human beings, women especially, seem ephemeral. Yet the image and phrasing she uses to bring to our minds the powerful sweep of Hokusai’s Great Wave Off Kanagawa.

Clearly, we can approach these novels through their common subject matter. Each narrator recounts a life of great hardship. Students might profitably examine to what extent these hardships can be attributed to the fact that the narrators are women. Or we can limit the discussion to considering to what extent the experiences of the narrators can be attributed to the historical period, the time, and the place, in which they live. In the novels by Defoe and Golden, the narrators spend part of their lives on the North American continent. Their mobility allows a global existence far different from that of the narrator of Saikaku’s work.

It would be wonderful if all students could explore in depth these fascinating novels. However, classroom teachers with little time or with concerns about the appropriateness of the subject matter find using even one or two short passages especially relevant to the objectives of a specific course, and the background and maturity of the students generate lively class discussion. The study questions below are clustered on content and literary devices. If the class is structured in work groups, each work group might be assigned a general area of questioning. When time allows all groups to explore both areas of focus, each group may be assigned at least one question from each subject cluster. After all work groups discuss the assigned readings and conduct research, they will want to share their findings in an informal presentation. As part of their sharing, students should be encouraged to create visuals, such as a Venn diagram illustrating the overlapping experiences of the three female narrators. In advanced classes, students can be required to present a fully documented research essay based on class discussion and research. The questions below touch on only a few of the issues raised by such a cross-cultural, multidiscipline comparative study.

STUDY QUESTIONS

Questions Concerning Subject Matter

1. Education: How and by whom is each of the narrators educated? What kind of education does each narrator receive? What can we infer about the culture from the education of girls? Compare the educations of the narrators, taking into consideration where and when each of these novels was written.

2. Economics: How do the heroines support themselves? What opportunities for employment are open to women in their cultures? Traditionally, women have worked with textiles. To what extent do these heroines follow this tradition? What are their marketable skills and attributes?

3. Religion: Where does the life of the spirit fit into the lives of the three narrators? Saikaku’s amorous woman ends her story as a Buddhist nun. Moll Flanders claims on the last page of the novel, “to spend the Remainder of our Years in sincere Penitence, for the wicked Lives we have lived.” Golden’s gray-eyed geisha retires to an elegant Park Avenue suite in the Waldorf Towers, comfortable but alone and far from home. However, all three women resist the temptation of suicide and achieve a measure of physical and spiritual ease. Where and how are the tenets of organized religions implied in these texts?

4. Motherhood: How does the absence of family, a mother in particular, influence the lives of the narrators? How does each of the heroines respond to pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood? How does the biological fact that women bear children relate to the values of the society pictured in the text to what we know of the historical and cultural context of each novel?

5. Exploitation: How do these texts relate to the long history of books and films that portray prostitution as romantic, even funny? Give specific attention to the tendency in the West to type all Asian women as sexually pliant, exotic, and submissive.

Questions Concerning Literary Devices

1. The three authors use some of the same symbols. Identify and discuss these symbols. Consider symbolic values attached to seasonal motifs, literal/metaphorical journeys, and artifacts such as paintings, poems, and dances. Identify and discuss symbolic constructs that you feel are culturally specific, as well as those you feel are universal to the human condition.

2. All three works are written in prose, although Saikaku was a gifted haiku poet, and long prose fiction works were relatively uncommon in the literary traditions of both Defoe and Saikaku. Both these authors are considered literary innovators for choosing to write what we today call “novels.” Speculate on the reasons these authors chose to write long narratives in prose.

3. In each of these novels, the author manipulates the point of view, creating a female narrator who tells her life story in retrospect. In what sense does using such a time frame create multiple points of view?

4. The authors of all three texts are men. Speculate on the reasons why these authors chose to write in a female voice.

5. All three novels contain sexually explicit scenes. Speculate on the intended effect on the reader. What effect do these scenes have on other messages in the novels? Are these works pornographic?

FURTHER INFORMATION

TEXTS

Dalby, Lisa Crihfield. Geisha. Berkley: University of California Press, 1983.

——. Kimono: Fashioning Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Hibbett, Howard. The Floating World of Japanese Fiction (translated from Kosgiku Ichidai Onna). London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Johnson, Shelia K. The Japanese Through American Eyes. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Keene, Donald. Japanese Literature: An Introduction for Western Readers. New York: Grove Press, 1955.

Marchetti, Gina. Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction. Berkley: University of California Press, 1994.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Random House, 1978.

Statler, Oliver. Japanese Inn. New York: Random House, 1961.

FILM/VIDEO

The first three films provide opportunities to analyze stereotyping. Other films listed below are directly related to the texts discussed in the essay.

The Geisha Boy. Dir. Frank Tashlin. With Jerry Lewis. Paramount Pictures, 1958. Color. 98 minutes. Not rated.

Madama Butterfly. Dir. Frederic Mitterand. With Ying Huang as Cio-Cio-Sen. Columbia/Tristar Studios, 1995. Color. 129 minutes. Sung in Italian with English subtitles. Not rated.

My Geisha. Dir. Jack Cardiff. With Shirley MacLaine, Yves Montand and Edward G. Robinson. Paramount Pictures, 1962. Color. 120 minutes. Not rated.

Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders. Dir. Terence Young. With Kim Novak. Paramount Pictures, 1965. Color. 126 minutes. Not rated.

The Life of Oharu (Saikaku Ichidai Onna) Dir. Kenji Mizoguchi. With Kinuyo Tanaka and Toshiro Mifune. Shin Toho and Koi Production, 1952. Black and white with English subtitles. 137 minutes. Not rated but R content. This film is based on Saikaku’s novel.

Moll Flanders. Dir. Pen Densham. With Robin Wright and Morgan Freeman. 20th Century/MGM, 1996. Color. 169 minutes. PG-13.

Moll Flanders. Dir. David Attwood. With Alex Kingston and Daniel Graig. WGBH Boston and Grenada Television (UK), 1997. Color. Four two-hour segments. Adult content warning.

INTERNET LINKS

Because Internet sites frequently change, teachers are cautioned to preview carefully all the suggested sites given in this essay with the needs of their own students and their own community standards in mind. All the sites listed were active when the essay was completed.

Asia Society Web site at http://www.asiasociety.org.

Creighton University Japanese Literature Web site at http://mockingbird.creighton.edu.english/worldlit/wldocs/texts.

Defoe films listed at http://us.imdb.com/Name?Defoe,+Daniel.

Five Colleges Center for East Asian Studies Web site at http://www.smith.edu/fcceas.

Golden biographical information and a question/answer Web site on Memoirs of a Geisha at http://www.randomhouse.com/vintage/read/geisha/golden.html.

Sackler and Freer Galleries at the Smithsonian Institution Web site http://www.si.edu/asia.

Ukiyo-e Museum Web site, especially for Eizan woodblock print to illustrate Saikaku’s amorous woman at http://www.cjn.or.jp/ukiyo-e/arts-index.html.

Ukiyo-e prints on the Internet with many good connections to other sites at http://www.bahnhof.se/~secutor/ukiyo-e/guide.html.

ADDITIONAL TEACHER RESOURCES

Japanese History and Literature Video Series (1996).

1. Classical Japan and the Tale of Genji (552–1185).

2. Medieval Japan and Buddhism in Literature (1185–1600).

3. Tokugawa Japan and Puppet Theater, Novels, and the Haiku of Bashō (1600–1868).

This useful three-part series, available from The Annenberg/CPB Collection (Phone: 1-800-LEARNER), surveys Japanese history and literature in chronological order. A teacher’s guide has been compiled and edited by Ninette R. Enrique for Columbia University’s Project on Asia in the Core Curriculum of Schools and Colleges. The third segment includes a discussion of Saikaku. The entire series helps establish a cultural and historical context for both The Life of an Amorous Woman and Memoirs of a Geisha.

The Pacific Century Video Series (1992).

Ten one-hour television programs easily divided into half-hour segments for classroom use. Focusing on the economic and political interconnections of Pacific Rim countries over the last 150 years, these programs provide useful background on issues raised in Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha. A textbook, study guide, faculty guide and excellent high school teacher’s guide prepared by MARJiS (Mid-Atlantic Japan in the Schools) at the University of Maryland are all available from The Annenberg/CPB Collection (Phone: 1-800-LEARNER).