PRODUCED BY REGGE LIFE

MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS FUNDING OF

THE CENTER FOR GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP OF THE JAPAN FOUNDATION,

AFLAC, AND HOSO BUNKA KIKIN

DISTRIBUTED BY STRUGGLE AND SUCCESS FILM LIBRARY

22-D HOLLYWOOD AVENUE, HOHOKUS, NJ 07423

1993. 85 minutes (55 minute version also available)

Reviewed by James T. Gillam

Are you a young African-American professional who would like to go to Japan for an extended stay? Are you anxious about how you will be received and how well you will be able to function once you get there? If you answered yes to these questions, then you should watch Regge Life’s Struggle and Success: The African-American Experience in Japan.

Struggle and Success is a documentary film that focuses on the experiences of thirteen African-Americans who have lived in Japan for extended periods of time. Despite what appears to be a singular focus on one ethnic group, this film includes a wide range of demographic and geographic experiences. Ten of the subjects are men. Three of them are women. One of the subjects is a paraplegic; two of them are married to Japanese women, and one of the couples has three children ranging in age from twelve to infancy. Their places of residence are scattered from the northern island of Hokkaido to more well-known cities such as Osaka in the east, Fukuoka in the west, and the Tokyo metropolitan area. Their careers are also diverse. The occupations of the subjects include English instructors, a partner in an import company, fashion designers, a securities broker, a broadcast executive, and a musical composer and television personality.

After a picturesque opening scene in a Japanese garden with a flutist playing in the rain, this film carries the viewer through a range of situations that progress from the simple to the complex as it portrays the struggles, successes, and yes, the failures, too, of African-Americans living in Japan. On the less complicated end of the scale is the portrayal of life for a single person on a temporary teaching assignment. At the other end of the spectrum are the dilemmas faced by a man who has married a Japanese woman and chosen to raise his family in Tokyo. Between these two poles are the situations of the single woman who learns to overcome some rather obvious gender discrimination, and the paraplegic who must cope with an obvious lack of accommodations for his physical limitations.

This film quickly departs from the obvious and basic notion that foreigners in Japan must make cultural and linguistic adaptations. It also demonstrates that there are special aspects of life in Japan, both positive and negative, that are uniquely part of the African-American experience there. One of the strengths of this film is its smooth transition from the experiences that are common to most foreigners to those that are unique to African-Americans. It does so in a way that teaches us about Japan and also makes some frank statements about life for African-Americans at home, too.

The first example of this binational examination is a discussion of the fact that initial interactions with most foreigners, African-American or not, are shaped by the perception of their professional position rather than color. It was that common experience that allowed Bill Whitaker, a network executive, and most of the other subjects to automatically acquire a status and the assumption of competence that is not universal in working situations for African-Americans in America. Rodney Johnson, an Osaka importer for the past twelve years, was also a ben eficiary of the formal side of working life in Japan. Both he and Panziella Lee, a fashion designer, were frank in their opinion that this aspect of life in Japan has given them access to business opportunities and financing that would not have been possible had they lived in America.

Although Whitaker, Johnson, and most of the other subjects had some unusual benefits in the formal world of work, they were also clear about the fact that, outside that controlled and formal environment, they encountered many situations where their foreignness, their color, or both factors, worked to their disadvantage. The most common of those situations was in the search for housing. It became painfully clear to some of the subjects that in Japan there are no legal or institutional barriers to housing discrimination. More importantly, the film points out that the problems the subjects encountered in this area were largely based on the export of racial stereotypes from the U.S. to Japan, and the persistence of those stereotypes over time.

Three academics discussed stereotypes in the film. The first, professor John Dower of MIT, said that his review of Japanese art shows a differentiation of status by color with lightness equaling higher status. John Russell, an anthropologist, has traced this phenomenon to the staging of a minstrel show, with white men in black-face makeup, by Admiral Perry at the conclusion of the Kanagawa negotiations that opened Japan to the West in 1858. Mitsuo Akamatsu of Tokashimabunri University noted that the construction of a color-status hierarchy in Japan preceded Perry, but he also said that the Japanese accept white, Western culture too uncritically. The result, clearly shown in the film, is that “Dacco Chan,” a term perilously close to “Darky,” is present in stores, the media, and the minds of many Japanese when they encounter African-Americans.

Clearly, the most complicated of the problems portrayed in this film were the interracial relationships. The first of these situations was that of Rodney Johnson, the Osaka importer. He and Wakako, his fiancée, both felt that they had been subjected to social and official opposition to their marriage. He was verbally harassed on the street. Then came numerous official difficulties. They both felt that the application process for a marriage visa was unnecessarily long and complicated. They were also subjected to calls to her parents’ home on a Sunday afternoon to be sure that they knew her fiancee was black. They felt these actions were anti-black, rather than antiforeign.

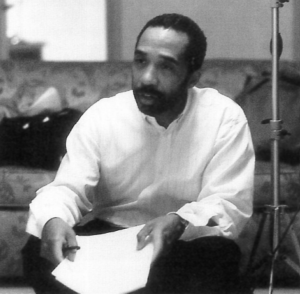

The most complex, and inspiring, study of an interracial relationship was that of the composer and TV personality, Ronnie Rucker, and his wife, Yoko. They have been married for twelve years and have three children. Mr. Rucker says Yoko’s brothers’ initial reaction was motivated by antiforeignism rather than racism. Her parents did not attend the wedding. Since that time, Mr. Rucker and his eldest daughter have become a regular feature on the Tokyo equivalent of Sesame Street. That fact, and his record as a devoted father of three children, the last of which is a son, has led Yoko’s father to accept Mr. Rucker completely. Yoko’s mother, however, still tries to send her grandchildren out for candy when her neighbors come to visit.

As I reviewed this film, I discussed it with African-Americans who have been to Japan, and those who plan to go there. To a person, members of the former group say that the film rings true to their experiences, and articulates things which they often misunderstood at the time. Those who plan to go to Japan felt that Struggle and Success is a timely, useful vehicle for calming their uneasiness and preparing them for both the common and the unique experiences of living in Japan. Given the increase in Japanese studies among African-Americans, whether they are at major universities or those that traditionally serve African-Americans, I think the officials at these schools would be well advised to show this film.