Daughters of the Flower

Fragrant Garden

Two Sisters Separated by

China’s Civil War

By Zhuqing Li

New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2022. 368 pages, ISBN: 9780393541779, Hardcover.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Author’s note: The memories of my two aunts, told to me over many years while I collected the materials for this book, are what has made this story possible. Other members of the Chen and Shen families, and other people whom my aunts knew and recommended that I speak with, have also contributed their recollections. All these memories have helped me to reconstruct the full story told in these pages. One of my aunts, however, has requested that I use a pseudonym instead of her given name. In deference to that wish, I have given her the pseudonym Hong. Except for that change, the stories told here are true to the best of my knowledge.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

They are two sisters born and raised in China’s southeastern coastal city of Fuzhou in Fujian Province. In a family that claims the last emperor’s tutor, Chen Baochen, as one of its ancestors, the girls had the privilege of traditional tutoring at home, in addition to their missionary school education—modern and bilingual—and had dreams as big as the world. The older sister, Jun, wanted to be a teacher, and the younger one, Hong, wanted to be a “big doctor”—in her own words—to get rid of the pain and suffering for every patient who would come through her office.

The girls grew up in their home known as the Flower Fragrant Garden, the Chen family compound crowning the peak of a small hill south of the city, overlooking the foreign concessions below. What the sisters could not have envisioned from their garden home was how their dreams would be shattered by wars and losses, their lives made and remade in separation, political recrimination, and self-preservation. They would both live into their nineties, separated by a divided China, and turned into each other’s enemies by the ensuing animosity between Taiwan and the Mainland, and yet both pursued careers devoted to helping their respective societies on each side of the Taiwan Strait. In the end, they would see both societies rejoin the world with renewed identities for a new century.

Jun and Hong were born in 1923 and 1925 respectively. They graduated from college in 1949, Jun from the Teacher’s College, and Hong from the medical school, two of the province’s very best schools, both located in Fuzhou. For Jun, the older sister, life seemed finally to smile at her after twelve years of family dislocation that had led to a series of major disruptions in her education. Her family had relocated to Nanping for the eight years of the war with Japan, where she had almost died of malaria. In the ensuing four years of the Civil War, the family lost its garden, and Jun realized that she had married a man whom she had never loved. But in the summer of 1949, while the Civil War raged on in the North, Jun and her best college friend, Qingxi, landed the two most coveted jobs after their graduation. They were both to teach at a prestigious private school near an island city called Xiamen, about a hundred and sixty miles south of Fuzhou. To celebrate their new beginnings, the two friends planned to spend some time in Qingxi’s home on a neighboring island called Jinmen, a half hour’s ferry ride just a mile east of Xiamen.

Jun knew full well from the start that her work would make her the enemy of her family.

As soon as Jun landed on Jinmen Island, she learned that her hometown Fuzhou had just been taken by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the armed forces of the Communist side. The PLA then took Xiamen, after sweeping through cities and towns with stunning rapidity. As Jun hesitated whether to return home to Fuzhou, the battle closed in on Jinmen, a tiny island of just a little over fifty square miles. Jun’s celebratory vacation turned into a nightmare, for on the rural island of Jinmen, she unexpectedly found herself on the front lines of the Chinese Civil War.

The retreating Nationalist (KMT) government decided to make Jinmen its last stand against the advancing Communist forces. Intense battles raged on Jinmen for two days. The PLA loss was total: the small number of survivors among the 9,000 PLA attack troops were taken hostage when their boats, stranded by the receded tides, were destroyed. The defending KMT’s Nationalist army, on their part, put their casualties at a third of the total PLA forces. With this decisive victory, the KMT army succeeded in holding the line of defense on Jinmen, thus facilitating a much larger overall KMT retreat to the island of Taiwan, a 100 miles to the east. To this day, Jinmen remains controlled by Taiwan, with the mainland China-Taiwan divide cutting right across that mile-long stretch of water separating Xiamen from Jinmen. From that moment of the KMT’s fending off the PLA on Jinmen, Jun would no longer be able to cross that mile-wide water to return to her home, to see her family in Fuzhou, or to start the job that was waiting for her. She was cut off from everything she had ever known. All her worldly possessions now amounted to a few changes of summer clothes, mostly still laying undisturbed in her small suitcase; and the autumn chill started to set in.

https://tinyurl.com/yckfs6wr.

Back on the mainland, Jun’s only full sister, Hong, two years her junior, was starting her medical residency in Fuzhou’s prestigious missionary-founded Union Hospital. Only weeks before the Jinmen Battle, Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing on the first of October. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) then set out on a wholesale restructuring of society: land reform, nationalization of private businesses, and systemic cleansing of what it deemed as the remnants from the old world that were incompatible with Party doctrine. In Hong’s hospital, a Party secretary replaced the head of the hospital, all foreign personnel were sent back to their home countries, and English signs of “welcome” were replaced by revolutionary slogans. Hong was asked to attend political study sessions intended to “rectify” her thought, contaminated ostensibly from her many bad political affiliations: her family’s feudal history, her father’s service in the Nationalist government before its retreat from the mainland, and now, her sister’s living in enemy territory. As the animosity between the CCP and the KMT solidified, the sisters—now separated across the Mainland-Taiwan divide—were turned into each other’s enemies. Gripped in the powerful historical forces that dictated their respective worlds, the sisters strove to not only survive, but also to find success and meaning in their striving. In the end, their very success would make their sisterhood irreconcilable.

After the Battle of Jinmen, Jun was trapped, but determined to build a life for herself somehow, seizing what came her way. She worked as a temporary teacher, then a local newspaper reporter, and finally, as a civilian liaison for the Nationalist Army’s Jinmen garrison. She waded deeper into the Nationalist establishment when she reported positively on the visit of Soong Meiling, Chiang Kai-shek’s wife, to the island. As a good student of history, Jun knew full well from the start that her work would make her the enemy of her family. She likely could have anticipated what would transpire, that her public work would lead to political persecution for Hong in particular, but also for her other half-brothers and half-sisters as they started to enter the workforce in Mainland China. But she also saw that no one would be able to change her kinship to the family or to get her home. She faced two impossible choices. She could let her life shrivel and her dreams die on the island, or she could find a future for herself even if her actions would hurt her mainland family politically. Then, she fell in love with a KMT general, Min, who oversaw civilian affairs in Jinmen and the surrounding islands. The trouble was, both of them were married back home on the mainland. Jun never had a child, but Min had two boys living with his divorced wife on the mainland.

In an effort to convince Jun to marry him, Min explained to her that the KMT’s victory in the Jinmen battle was as decisive as the Allies’ D-Day operations at the end of World War II, and that the PRC’s heavy losses in the subsequent Korean War raging at the time would put a hold on its abilities to invade KMT-held territories. Jun married Min, and the couple decided that—as Min put it—they should not remain “exiled” on Jinmen either for an enemy that would be unlikely to regroup anytime soon, or, for reinforcements that, in the event of an attack from the Mainland, would never arrive in time from Taiwan. They should instead transition to civilian life in Taipei, the capital city where things were happening.

The person on the mainland that was hit the hardest by Jun’s presence on Jinmen, and later her marriage to a KMT general, was her only full sister Hong, now a rising star in the hospital. Hong was put on probation for her family’s and her own suspected affiliations with the KMT, and forced to go through rounds of political study sessions. Hong could see that, to survive in the new Communist China, she had to fall in line, and cut free of the ties to Taiwan and the Nationalist past. She had to take a political stand to save her own career, revive her family’s fortunes, and give herself and her siblings a chance to rise in the “New China.”

She burnt the few letters that Jun had sent her from Jinmen. She wrote self-criticisms as demanded by the Party, declaring her resolution to stand firm with the CCP, and she volunteered to lead medical teams on repeated tours to the countryside to care for the rural poor, the core supporters of the CCP. Just like her sister on Jinmen, Hong made a series of conscious choices, and worked to internalize the rationale. Cutting off communication with her sister was like cutting off a limb to ward off gangrene, and volunteering to care for the rural poor women was to search for meaning in her work as an ob-gyn doctor. In a way, she too, like her sister, was facing impossible choices at the same juncture. And, her choices would not just be personal, but would affect her entire family on the mainland.

In the absence of Jun, younger sister Hong now became the oldest girl in her father’s large family. Hong’s father, my maternal grandfather, was an early graduate of China’s first modern military academy, the Baoding Military Academy, and had served in important positions in the Nationalist government of “Old China.” Much as in the film Raise the Red Lantern, where having multiple wives was the privilege of the wealthy and powerful, he had two wives, my two maternal grandmothers, whom I called Upstairs Grandmother—Jun and Hong’s mother—and Downstairs Grandmother, my mother’s mother. In the New China, Hong’s father and his family became the very symbol of the feudal past that the CCP wanted to clear away. Caring for them would put Hong at risk of becoming the people’s enemy. Then, in 1952, her father, the sole provider and protector of his large family, contracted tuberculosis, and died, only weeks before streptomycin, the first effective drug for the disease, became available in Fuzhou. At his deathbed, Hong promised to take care of his family. It was out of her physician’s instinct, but she was also putting her faith in the idea that life in “New China” would get better. At his death, Grandfather left behind Upstairs Grandmother, whose three children had all grown (Jun and Hong had an older brother), and Downstairs Grandmother, with her six young children (Jun and Hong’s half-siblings), and one more on the way. Hong was the only person in the family with an income at the time. She pinched every penny, and still barely kept everyone from starvation. Grandfather’s passing at fifty eight was a tragedy, but Hong saw her father’s untimely death as the clearest severance of her family’s connection, and her own, to “Old China.”

be united with to strike surely, accurately and relentlessly at the handful of class enemies.” Source: Chinese Posters website at https://tinyurl.com/2p95znx4.

To lead the family in the new Communist order, she saw the need to construct a narrative for a new life, for herself, and for her family. The theme of that narrative for her own medical career would come to her in her patients’ refrains of gratitude. The CCP was the first government since time immemorial, they told her, that sent highly-trained, urban doctors like Hong to remote corners of the countryside to cure ordinary people of ailments, all free of charge. To this day, she weaves her work into that narrative, sees herself as an instrument in that effort, and derives genuine pride in having delivered modern healthcare to rural women who would otherwise never have the chance.

In the new Communist China, Hong too married and started her own family. In successive waves of political movements, she repeatedly declared her innocence of any ties to the old KMT order. And to prove her belief in Communist values, she continued to volunteer to work double shifts and to take grueling countryside tours to treat the rural poor. She was determined to try with all her might to build a better world for herself and her young children.

Thus, the two sisters, equally well-educated and equally ambitious, made similar kinds of bargains on the respective sides of the divided China that they were now located: to live, and to find meaning in their lives. But those prospects that Hong had fervently wished and worked for came crashing down during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) when she was sent to a remote village for more than two years, alone without her family. The cause of her travails was the same set of bad family and personal political connections that had doggedly pursued her from the beginning of the Communist takeover.

Hong was stripped of her medical license, taken out to be paraded down the streets, and forced to stand at the gate of her hospital, humiliated with a half-shaven head and a plaque hanging down from her neck written with the characters: “Counter-revolutionary Quack Doctor.” Tens of thousands of the best educated professionals like her across the nation suffered a similar fate. But many of those succumbed to the torture and/or humiliation, and many of those who survived turned bitter.

Hong was different. Looking back to her humiliation and exile, Hong insisted that what pained her the most was the waste of her best years of practice when she could best provide care to rural women. But she accepted the CCP’s apology and its acknowledgement that exiling her was a historical mistake. Whether or not this was Hong’s true feeling, she now sticks to this standard narrative, one that she uses to construct her public persona. Like burning her sister’s letters years earlier, she “disappears” the past and her true personal feelings that do not fit neatly into the Party’s revolutionary message. It is this public narrative that she has shared with me and presented publicly in her slim memoir written for her ninetieth birthday. This supremely disciplined woman simply keeps two books of her life separate: one public, the other, which no one would ever likely read, buried deep in her own heart. In this public narrative, the two years of political exile and hardship amount to a revelation and redemption: the hardship that she suffered while living alongside the poorest of the poor had opened her eyes to a world that her privileged upbringing and the best education would never have shown her. The CCP had sent her to the remotest corners to be “re-educated,” farming with the locals who, for generations, had eked out a living in narrow strips of terraces on the steep hills. And there, Hong did find the gems that the CCP had intended to deliver to people like her: the decency of the poor despite the hardship, the CCP’s care about their hopeless plight, and its determination to lift them from the ravages of poverty. She wanted to be part of that CCP effort then, and she still wants her legacy to be part of that revolutionary cause.

Central to Hong’s medical mission, as she put it, was to restore the human body’s functions with her skills. This worked well when she spearheaded the campaign to eradicate the two most debilitating and yet most curable ailments that disproportionally plague rural women: fistula and uterine prolapse. Both ailments primarily inflicted rural women, due to child-bearing at a young age and early resumption of heavy physical labor after childbirth. For many years, Hong’s professional philosophy was in sync with her political principle: to support the Communist advocacy for women’s independence and dignity, to advance the Communist cause by bringing in more emancipated women into the workforce, and to improve China’s healthcare index.

But that mission hit a snag in the government’s drive of population control in the 1980s. She was assigned to lead the campaign in her home province of Fujian to enforce a drastic reduction of the birthrate. One never declines a Party’s assignment, and definitely not Hong. Deferring would be a gesture of protest. But this assignment directly contradicted her medical principles. To terminate young women’s birthing ability was the direct opposite of fixing the body. Her real conundrum, however, was more nuanced and entangled. She agreed with the CCP that a rapidly expanding population would burden the nation’s modernization efforts. But, she felt that population growth should be reduced at a rate that was more medically realistic, and it should be done through education rather than force. But, it was not her place to determine policy, and she did not have the power to do so anyway. So she instead worked strategically to help ameliorate the policy’s devastating impacts on women and their families.

Her efforts achieved a degree of success. When state-imposed family planning finally started to ease up a decade later, Fujian Province’s statistics showed that in 1990, its population increase was on the higher side at 16 percent, compared to the national average of 14.39 percent.1 But the male-to-female ratio was within the normal range of 100 boys to 103–106 girls at the ratio of 100:106, with an average of 2.4 children per woman.2

Hong was in her seventies at the century’s end. China’s reform and opening had by now propelled the country into a new modern era, and the technical team in her hospital was experimenting with in-vitro fertilization (IVF) technology to help women who were having difficulty conceiving. After the team’s repeated failed experiments, Hong decided to tackle the new technology herself. She successfully delivered the province’s first two live births from IVF in 1999.

Over the years, Hong has found, and for the most part, successfully tested, the narrative she constructed to survive and succeed in New China—to help lift the down-trodden of the past, to restore the body’s normal functions, and to advance China’s healthcare to the level of the advanced nations. This narrative hits at a sweet spot where her career and the Party’s revolutionary cause come together. Any dissonance from this theme, she would screen out in order to safeguard this singular tabulation of her path to success. And her narrative is validated in the accolades that the nation has piled on her. The Party that had persecuted her invited her to become a member, an extremely rare honor; the province elected her as a representative to attend the 1995 World Women’s Conference, and the mayor of Fuzhou at the time designated her to deliver their daughter. This mayor, Xi Jinping, would eventually become the President of China and the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

For Jun on Taiwan, where she and Min started their civilian life after their marriage, it meant putting aside her dreams of teaching history and literature, and instead be willing to take up whatever opportunity came her way just to get started with life. But before the couple had settled down in the capital city Taipei, the past caught up with them. Min’s two teenage sons had escaped from the mainland in 1954 and 1957 respectively to find their father, bringing with them stories of Communist persecutions and seemingly random executions of landowners and families with KMT ties such as theirs. The boys’ mother, who had since been divorced by their father, pushed the boys out the door in what must have been a heart-rending separation for a woman who had raised these two boys after having been abandoned by her husband. She believed that their only chance of survival was to flee the Mainland and find their father, a general in the Nationalist army. Min’s sons’ gory tales of the revolutions on the mainland struck deep fears in Jun’s heart. Not knowing of her own father’s passing by then, Jun was haunted by the possibilities of her own family’s sufferings because of her father’s past and her own presence and work on Jinmen.

But there was nothing that she alone could do to change the political situation. The best thing she could humanly do, she decided, was to care for and love these two boys just as she would her own. Though she and Min had three children of their own soon after, Jun saved every penny to make sure that Min’s boys attended the best private schools and then elite colleges.

At the same time, Jun searched for ways to find a meaningful career outside of home, hoping also to contribute to the growing family’s finances. The search ended in an unexpected purchase of a friend’s import and export company that mainly handled grandfather clocks. As soon as Jun took over the company, she sensed that Taiwan was transitioning into rapid industrialization after its successful land reform. So, she decided to shift the company’s business to importing machinery instead. Her first imports were Taiwan’s first street sweepers, vehicles built by the Ford Motor Company. This transition to machinery enabled the company to play a key role in the Republic of China’s rapid industrialization in Taiwan in the late 1950s and 1960s, thus making Jun one of Taiwan’s pioneering female CEOs.

Jun’s success in running and expanding her company came to an abrupt halt when she was diagnosed with colon cancer. Waking up from the surgery, she had a religious epiphany, and her Christian education in missionary schools came back in full force. Central in those memories were the moments of her mother reading the Bible with her. Her precarious health reminded Jun that her time was running out if she was to see her Fuzhou family again in her lifetime.

It was 1972, and Nixon visited the PRC, with a longer-term plan, it seemed, to normalize the US diplomatic relationship with the Mainland. The Shanghai Communique that came out of the visit indicated that any US normalization with the PRC would be predicated on America’s cutting diplomatic ties with Taiwan, a longtime US ally. Following Nixon’s trip to Beijing, a groundswell of international realignment ensued, with nation after nation shifting their diplomatic relationships from Taiwan to the Mainland. Even as she recuperated from her colon cancer operation, Jun could see Taiwan’s increasing isolation in the world, and understood that it would make her return to the Mainland directly from Taiwan almost impossible. In search of a stepping stone to return home to Fuzhou, she decided to travel to Europe and America to find a third country, one with diplomatic relations with the PRC.

What she found was more than a stepping stone. At Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie, she “saw the face of separation.” The barbed wire atop the Berlin Wall looked to her as “withered vines with thorns.” On the Normandy Beaches and the white marble headstones of the cemetery above Omaha Beach, she saw the monuments of sacrifice, and the peace that it restored. But the footprints of war in Europe—a continent away from Jinmen Island where she started her own separation—stood as a stark contrast to a different kind of separation she had to live with. The hostility between mainland China and Taiwan never had a resolution. The sacrifice of the 9,000 PLA and 3,000 KMT soldiers at the Battle of Jinmen never had a monument. And, China’s split as a result never did have a demarcation. A quarter of a century before, Min, her suitor on Jinmen Island at the time, had compared the Battle of Jinmen to the D-Day operations as a decisive moment in the course of China’s own conflict. And now it was on the European continent that Jun finally found places to mourn her lost years with her family. But it would be in America where Jun would find her stepping stone home. She received, and accepted, a friend’s offer to take over her restaurant in Maryland as an investment immigrant. If Nixon could go to China, Jun reasoned, she would too.

When Jun left home in 1949, she had left for a brief celebratory summer vacation with her friend on Jinmen Island. Thirty-three years later, she would make her trip home as an overseas Chinese, not a homecoming daughter. She would be going through a border crossing at Luohu from Hong Kong to enter the PRC, holding a Taiwan (ROC) passport, a US travel document, and a PRC—mainland China visa. The family and home that she had yearned to reunite would not be the same, and the past that she’d wished to rekindle, she’d soon see, could not be found in the family’s new narrative constructed for surviving and succeeding in Communist China. Indeed, she found that she herself would be absent from the family’s own internal narrative edited for “New China.”

The two sisters, Jun and Hong, had been born to a family whose wealth, prestige, and progressive values all but ensured the girls an easy path to the life of a modern woman. But waves of tremendous upheaval swept across their country and upended their lives time and again. The closely-bonded sisters would be turned, at least officially, into each other’s enemies. The political implications of their accidental separation would threaten their lives, careers, and even their families. These two girls who seemed to have been destined for a life of privilege and ease learned to leverage their superb educations to develop their political acumen, their ambitions for their drive to succeed, and their sensitivities to protect their families. In the process, they managed to harness their own destiny and become true modern women. Hong would travel the world into her eighties, showcasing the Mainland’s medical advancements in conferences, and Jun would end up being a restaurateur of local renown in Maryland after making her imprint in Taiwan’s economic development from late 1950s to 1970s. But in the end, they each would be so deeply shaped, and their successes so closely defined by their different societies, that their attempts at personal reconciliation would fail to restore their sisterhood.

Classroom Discussion Questions

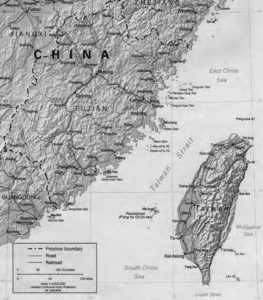

1. Find the following places on the map: Fuzhou, Xiamen, Jinmen, Taiwan. Considering the two entities that emerged from the Chinese Civil War—the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the Mainland and the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan—who controls these geographies today?

2. How did the sisters’ family prepare them to be modern, independent women? In what ways did the home environment in which they were raised combine aspects of traditional and modern values?

3. This article refers at times to the sisters as enemies. Were they ever enemies? Why or why not?

4. As suggested in the story, Hong burned the letters and erased her sister from the family’s history. Why did she do this? Do you feel it was something she had to do, or was it more of a voluntary decision?

5. What goals and aspirations was Hong trying to achieve as an OB–GYN doctor? How, if at all, did these aspirations come into conflict with the government’s policies? How did she reconcile these tensions?

6. In some ways, Hong suffered under the Communist regime, including being exiled to the countryside and being subjected to public humiliation. Yet, for Hong, becoming a member of the Chinese Communist Party and serving the country were essential parts of her identity. How do you understand this choice on her part? Does this make sense to you? How do you think it made sense to Hong?

7. How do you assess Jun’s choice to become involved with the military forces on Jinmen, and then to become a prominent member of leading social, economic, and political circles on Taiwan?

8. In what ways does the story underscore the particular burdens, challenges, and responsibilities for women during times of conflict, crisis, and upheaval?

9. This article shows that even decades after the Chinese Civil War concluded, it still has lasting impacts on individuals and families. Can you think of other historical examples of conflict that have had similar effects? Can you think of comparable experiences in your own extended family or among people you know?

1. See data from The Fourth National Population Census of the People’s Republic of China at https://tinyurl.com/2kkw962t; The Chinese National Bureau of Statistics

at https://tinyurl.com/mrykr3ss, and the China Data Center at: https://tinyurl.com/w22njj2t.

2. “Fujian Province had nearly 30 million inhabitants in 1990, an increase from just over 1.2 million in 1950. Like China as a whole, Fujian Province has a fairly high sex ratio, about 107 males per 100 females. The agricultural population continues to be predominant, but the nonagricultural section is growing faster. Fujian’s birthrate was reported to be about eighteen per 1,000 population in 1992, having declined from a post-famine high of forty-five per 1,000 around 1963. On average in 1989, Fujian women had about 2.4 children, only marginally higher than the average for all China, and by 1992 the number of births per women had declined further.” See Judith Banister, et al. “Population and Migration Characteristics of Fujian Province, China,” Center for international Research, US Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC 20233-3700, CIR Staff Paper No. 70, November 1993, at https://tinyurl.com/2n8nnte5.

FURTHER READINGS

Chang, Jung. Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China. New York: Anchor Books, 1992.

Kan, Caroline. Under Red Skies: Three Generations of Life, loss, and Hope in China. New York: Hachette Books, 2019.

Spence, Jonathan. The Search for Modern China. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

Zia, Helen. Last Boat out of Shanghai. New York: Ballantine Books, 2019.