We would like to thank Dan Duffy, editor and publisher of the Việt Nam Literature Project, for providing this tribute to Nguyen Chi Thien, an outstanding twentieth-century Vietnamese poet who recently died. What follows is a short essay about Thien accompanied by examples of his poetry.

My Mother

My mother on anniversaries or festival days

is wont to put her hands together and pray for a long time

Her old saffron dress has somewhat faded

But I would see her take it out for the occasion

My life being full of suffering and injustice

Mother always has to pray for me

A son who has seen a number of jail terms

Causing tears to flow in streams on Mother’s cheeks.

Sitting next to her, I find myself so small

Next to the great vast love of my mother.

Mother, I only have one real wish

And that is, never to be far away from you!

Now each time that you sit in prayer

For your sick prisoner son in the deep jungle

The old, fading saffron dress you wear

Must be soaked with tears unending!

Nguyen Chi Thien, 1962

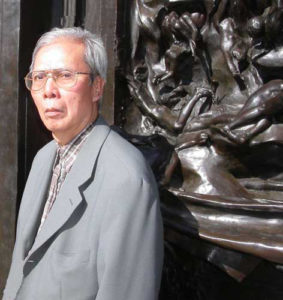

Nguyen Chi Thien, a Vietnamese dissident poet who spent twenty-seven years in Communist prisons, died on October 2, 2012, after a long illness. He was born in 1939 in Ha Noi. His father worked as an official in the municipal court, and his mother sold small necessities in the neighborhood. At the end of 1946, when the war between France and Việt Nam broke out, his family fled to their native village in the countryside.

In 1949, the family returned to a more stable Ha Noi, and Thien started school in private academies. After the defeat of the French in 1954, he cheered the return of the Việt Minh revolutionaries.

The drama of Nguyen Chi Thien’s life begins in Haiphong, the strongly Communist port city of northern Việt Nam. When Thien contracted tuberculosis in 1956, his parents sold their house for money to treat their son. The authorities already held Thien in suspicion because his brother had joined the National Army. In December 1960, Thien unwittingly stepped over the line while teaching a high school class for a sick friend. Thien noticed the history textbook taught that the Soviet Union had defeated the Imperial Army of Japan in Manchuria, bringing an end to World War II. Oh no, he told his students, the United States defeated Japan when they dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nguyen Chi Thien paid for this remark with three years and six months in labor camps on a sentence of two years. He met other literary men in jail, composed poems in his head, and learned them by heart. In 1966, he was returned to prison after a short release.This time, the police charged him with composing politically irreverent poems circulated in Ha Noi and Hai Phong. He denied it, and spent another eleven years and five months in labor camps. Authorities never brought him to trial for lack of evidence, but they had the right man.

In 1977, two years after Saigon fell, Thien and other political prisoners were released to make room for officers of the Republic of Việt Nam. He had been composing poems all the while and now seized the opportunity of freedom to write them down and bring his art to the world.

If Tomorrow I Have to Die (1959)

If tomorrow I have to die

I still would not regret my springtime

Life no doubt is lovely, inestimable

But suffering has taken its toll—gone is the best part

In the deserted night I look at the distant stars

And let my soul drift into the past

For a minute I am oblivious to the cruel reality

And forget all about hunger, cold and bitterness.History takes me back in time

To that golden age of sumptuous pavilions and palaces

To scenes of success at the imperial exams with

long chaise and parasols

To scenes of poor scholars reading through the night

Once again, I find Confucians of integrity

Who choose poverty and stay away from the citiesThen I see virginal and virtuous country lasses

Weaving silk on their looms near a pool with water jets

In dream I witness joyous festivals

And paddy threshing on golden moonlit nights

Images I tenderly nurture in my heart

Where there still lingers the echo of immense river calls

And the smooth clip of a shuttle going back & forth

I love the forests dense and dark

Full of dangers and secrets, exuding with lifeI love also and miss the gongs that give the alarm

Sinister-looking thieves’ dens and the path thereto

Scenes of war with horses neighing and troops clamoring

Also fascinate me, bewitch my soul!

Why I do so, I know full well

That in old days there were emperors and mandarins

That life was riddled with injusticeWhy is it that I dream only of the better facets,

That only glories of the past seep through to my poetry?

That I am forgetting the seamier side?

Can it be that life today Is filled with poison in its very innards

Whereas the old society’s defects were mere pimples?My Poetry (1974)

There is nothing beautiful about my poetry.

It’s like highway robbery, oppression, TB blood cough.

There is nothing noble about my poetry.

It’s like death, perspiration, and rifle butts.

My poetry is made up of horrible images

Like the Party, the Youth Union, our leaders, the Central Committee.

My poetry is somewhat weak in imagination

Being true like jail, hunger, suffering.

My poetry is simply for common folks

To read and see through the red demons’ black hearts.

Two days after Bastille Day, on July 16, 1979, Thien dashed into the British Embassy at Ha Noi with his manuscript of four hundred poems. He had prepared a cover letter in French, but the embassy of France was closely guarded. However, British diplomats welcomed him and promised to send his manuscript out of the country. When he got out of the Embassy, security agents waited for him at the gate. Dragged to Hoa Lo prison, the famous Ha Noi Hilton, now empty of US flyers. He spent another twelve years in jail and prison camps, often in stocks in solitary darkness, for a total of twenty-seven years’ imprisonment. Meanwhile, the British diplomats kept their word. Thien’s manuscript collection, Flowers of Hell, appeared in Vietnamese in two separate editions overseas.

Thien had the great satisfaction of seeing a copy of his book waved in his face by his angry captors. He did not know that his poems also were translated into English, French, German, Dutch, Chinese, Spanish, and Korean. They were set to music by the great Pham Duy and sung around the world. While their author lay in irons, his poems won the International Poetry Award in Rotterdam in 1985. Six years later, the poet was released from jail. He lived in Ha Noi under close watch by the authorities, but his international following also kept an eye on Thien.

Human Rights Watch honored him in 1995. That year, he emigrated to the US, thanks to the intervention of Noburo Masuoka, a retired Air Force colonel who was drafted into the US Army from an internment camp for Japanese Americans in 1945. Thien lived in Virginia, the home of his brother, Nguyen Cong Gian, whom he had not seen for forty-one years.

As if released from prison once more, Thien wrote down another book’s worth of poems from memory. Three hundred Vietnamese poems and some select English translations were published in 1996. In 1998, the International Parliament of Writers awarded Nguyen Chi Thien a three-year fellowship in France. He lectured around Europe while he wrote and published a collection of short stories, rooted in the reality of his years in Hoa Lo prison.

Nguyen Chi Thien returned from France to Orange County, California, where he took the oath of American citizenship in 2004.

Editor’s Note: This article is based on biographical information for Nguyen Chi Thien found online at The Vietnam Literature Project at http://www.vietnamlit.org/nguyenchithien/