Like many countries around the world, Canada is becoming more attentive to its economic and diplomatic relationship with countries in Asia. This is especially the case with China, now Canada’s second-largest trading partner (behind only the United States). Public opinion is an important, though not always well-understood, facet of these relationships. Since 2004, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) has conducted regular national opinion polls to gauge Canadians’ views on a range of issues in the Canada–Asia relationship. APF Canada is a not-for-profit organization headquartered in Vancouver and focused on Canada–Asia relations. The surveys provide a baseline understanding of public attitudes on issues ranging from economic ties to geopolitical considerations to education about Asia in Canada. In addition, these polls also give us a sense of how or whether these views change over time, and what role demographic factors—sex, region, ethnic background, formal education, and income level, for example—might play in shaping these views.

By the next Canadian federal election in 2019, Canadian millennials will be the country’s largest potential voting bloc.

One demographic factor that has interested us is age, specifically whether younger Canadians differ from older Canadians in how they view Asia. On a general level are questions of favorability—do younger Canadians have “warm” or “cool” feelings toward different countries in the region, and what do they most associate with those countries? On a more specific and policy-relevant level are economic relations: do younger Canadians support free trade agreements with Asian countries, and at what cost to so-called Canadian values? To gain insights into these questions, APF Canada conducted a series of research and youth-engagement activities from July 2017 to March 2018. The anchor project was a November 2017 survey of Canadian millennials, defined as those aged eighteen to thirty-four at the time of the survey.1 We supplemented the survey analysis with focus groups and twenty-two semistructured interviews. In addition, we used some of the key survey results as a tool for engaging local university students in discussions on their generation’s views of Asia.

As we acknowledge in the survey report, categorizing people into generations is not an unproblematic exercise. The line separating one generation from another may seem arbitrary, and there will always be important exceptions to generalizations. Moreover, we cannot say with certainty that attitudinal differences that emerge in the survey results are due to age and not other factors. However, our data, not just from the recent poll, but in polls going back to 2004, indicate that when it comes to Canadians’ views on Asia, age matters. Why do millennial views deserve close attention? In the Canadian context, there are three overriding reasons.

First, by the next Canadian federal election in 2019, Canadian millennials will be the country’s largest potential voting bloc. This is not to say that all of them will turn out to vote; as in other countries, voter participation rates among Canadian youth tend to be lower than for older Canadians. However, there may be reasons to believe this is changing. According to Canada’s Abacus Data, voter turnout among eighteen- to twenty-five-year-olds increased by about twelve points in the most recent federal election (2015). In addition, Abacus suggests that 2015 “may have been the start of a political awakening” of Canadian youth, a voting bloc it describes as a “new electoral powerhouse in Canada.”2 If that prediction is correct, the views of millennials will be of particular interest to Canada’s three major political parties, all of whom will be actively seeking their support.

Millennials’ views will matter at a pivotal time in Canadian foreign engagement. Canada’s economy has historically been heavily dependent on trade with the United States. But the 2016 US election has threatened to upend the status quo, especially the terms of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This is prompting Canadians to get serious about looking elsewhere for key economic partnerships. That “elsewhere” is the Asia–Pacific, including key markets like China, Japan, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). To date, the rise of antitrade sentiment has not taken hold among the Canadian public the way it has in the US and parts of Europe. Indeed, a June 2018 APF Canada poll shows that a majority (53 percent) of Canadians are concerned that Canada is falling behind international competitors in gaining access to Asian markets. As such, a majority also support free trade agreements with China (59 percent) and India (66 percent), an increase over previous years.3 It is a matter of political expedience for politicians and policymakers who are courting millennials’ support to get a more fine-grained understanding of the latter’s views on these issues.

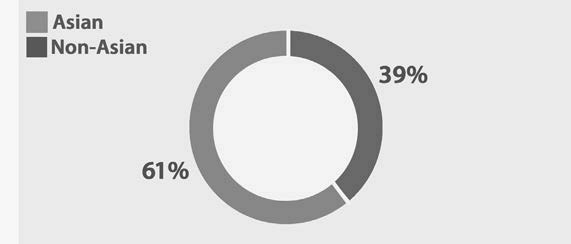

Second, millennials are the most “Asian” age cohort in Canada. According to the 2016 Canadian census, more than one-fifth of Canadians are foreign-born. Seven of the ten top source countries for immigrants to Canada in the last five years are Asian, with the Philippines being the largest source country, followed by India and China. These family and heritage connections with Asia are evident in our survey results. As seen in Figure 1, when asked, “Can you speak an Asian language well enough to conduct a conversation?” 23 percent of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds said yes, a sharp increase from the 8 percent of twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-olds who can speak an Asian language and the 2 percent of Canadians over the age of thirty-five. As seen in Figure 2, most (61 percent) of those who answered yes to the previous question self-identified as Asian. On one hand, we are careful not to make assumptions that one’s attitudes toward Asia are determined or necessarily shaped by one’s heritage. Still, we recognize that firsthand exposure to Asia through such connections cannot be discarded as an important factor. As we discovered in our focus groups and discussions, participants with Asian heritage had widely varying levels of firsthand familiarity with Asia, and by no means did this group have a uniformity of views.

Seven of the ten top source countries for immigrants to Canada in the last five years are Asian, with the Philippines being the largest source country, followed by India and China.

Third, young millennials in particular are coming of age professionally and politically at a time when “the rise of Asia” is not a hypothetical or future scenario, but a concrete reality. As in other countries, there are daily reminders of Asia’s—especially China’s—growing economic, diplomatic, and political clout. Never in Canada’s history has public opinion on the relationship with China mattered more than it does now. In addition, for the first time in modern history, Asia includes a strong China and a strong Japan. In the coming decades, a strong India may be added to that constellation. Getting a baseline of young Canadian views of this region is thus important; it will be equally important for us to track how these views change in response to global gravitational shifts.

What did we learn from our survey about the views of millennials?

CANADIAN MILLENNIALS’ VIEWS ON ASIA: KEY SURVEY FINDINGS

The survey was conducted in September and October 2017 with 1,527 Canadian adults. This included an oversampling of respondents aged eighteen to twenty-four to ensure that the number of responses would be adequate for a detailed analysis of this age cohort’s views. Overall, the survey pointed to two key findings:

(1) There are intragenerational differences

On several questions, there was a pronounced difference in views between younger millennials—those aged eighteen to twenty-four—and older millennials—those aged twenty-five to thirty-four. Unsurprisingly, the younger cohort describes themselves as still forming their opinions about a lot of issues. Also unsurprising was a higher incidence of “don’t know” responses to questions in the survey. Their older counterparts, in contrast, report being fairly well-informed and having well-established views.

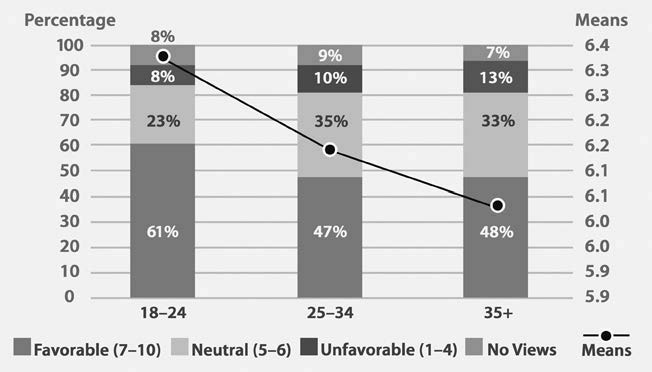

(2) Young millennials are more positive about Asia

Compared to Canadians over the age of twenty-five, younger millennials are more positive toward Asia. As seen in Figure 3, 61 percent of this cohort says they have favorable views, compared to 47 percent and 48 percent, respectively, for both older millennials (ages twenty-five to thirty-four) and Gen Xers and boomers (over ages thirty-five). Unsurprisingly, young millennials report getting most of their information about Asia from social media; however, discussions with members of this age cohort suggest that the original sources of information do not differ substantially from what is typically consumed by Canadians twenty-five and older. The focus group and large group discussions yielded additional insights into these views and will be discussed in greater detail below.

CANADIAN MILLENNIALS’ VIEWS ON ASIA: KEY FINDINGS FROM FOCUS GROUPS, INTERVIEWS, AND LARGE GROUP DISCUSSIONS

In a word-association exercise, we asked participants to name the country or territory that comes to mind first when they hear the word “Asia.” The overwhelming response was “China.”

As noted above, we supplemented the survey analysis with two focus groups (with nine and seven participants), twenty-two semistructured interviews, and two group discussions (one with fifty participants and the other with thirty participants). The vast majority of the participants were young millennials, but by no means a representative sample of this age cohort. Although they were not all from Vancouver, they all lived there at the time of their participation. Vancouver is a very “Asian” city, both in its commercial orientation and in the family background of much of its population. (Whites are now the city’s largest visible minority.) In addition, our discussion participants were all receiving or had received a university education and said they were regular consumers of information about global issues and Canadian foreign policy. One focus group consisted of students from a class on ethics and world politics at a local university. Some of these participants, in addition, were simultaneously enrolled in courses on Chinese politics and global China. The two large group discussions took place at another university with students in a course on protecting human rights. Not all of them self-described as being particularly interested in or informed about Asia, which gave these discussions some interesting variety.

Given that the focus group and discussion participants were part of an educated elite, we were cautious about generalization. Indeed, one of the limitations of this work is that the insights provided by the discussions capture only a specific subset of educated youth. Nonetheless, we determined that it was valuable to have a more in-depth understanding of the views for two reasons. First, these discussions provided a window into the evolving thought processes of millennials who were actively learning about Asia and Canadian foreign affairs. Second, their fields of study (political science, international relations, economics) meant they were very likely to be among the more politically active and engaged members of their generation, and possibly even in positions of political or economic influence later in their careers.

What did we learn from our discussions with this key subset?

MORE NEUTRAL VIEWS OF CHINA

One of the main points of discussion was this group’s overall impressions of China. In a word-association exercise, we asked participants to name the country or territory that comes to mind first when they hear the word “Asia.” The overwhelming response was “China.” We then asked them to name the two words that come to mind first when they hear the name of that country. Here, two main patterns emerged. One was the word “economy” and related imagery, like “manufacturing,” “factory,” and “made in China.” However, there was a subtle shift from the imagery of China twenty years ago, somewhat away from the image of China as the “factory to the world,” and toward China as an economic juggernaut, with words like “power” and “powerhouse” being attached to the “economy” label.

The second pattern was words that referred to China’s rapidly rising position in the world. That included words like “power,” “scale,” and “rising.” What was notable about the tone of the ensuing discussion was a relative lack of expressions of anxiety about what China’s rise would mean for the future. Instead, China’s growing global heft was a fact that many participants accepted, rather than a cause for concern. Words regarding China’s political character, such as “authoritarian,” “communist,” and “one-party state,” were also mentioned but with less frequency. Similarly, issues related to the environment and growing technological sophistication also surfaced, albeit also with less frequency.

PRO-VALUES, BUT NOT AT ANY COST

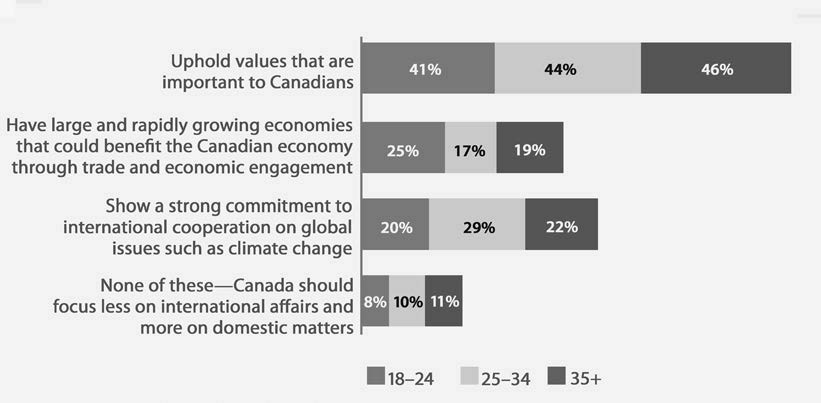

One of the perennial debates in Canadian foreign policy is the so-called values versus the economy debate. In other words, what should the balance be between projecting Canadian values—for example, the rights of women, indigenous peoples, and sexual minorities—and pursuing economic benefits? As noted above, a more recent APF Canada survey showed both robust support for closer trade ties with Asian countries and relatively high support for the current government’s “progressive” trade agenda, which aims to negotiate labor and environmental standards, along with protection of vulnerable groups, into such trade agreements. The 2017 millennials survey found that among young millennials, there is a somewhat-higher preference for prioritizing relationships with countries that have large and growing economies, although support for values still ranked higher (see Figure 4).

The focus groups and discussions uncovered an interesting nuance in these views. In order to move the discussion from the abstract to the concrete, we used the example of Norway’s tense relationship with China after the Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010. Participants read a brief description of that case, including a short description of the economic blowback Norway suffered as a result. (Participants were informed that the Nobel Committee is independent of the Norwegian government, but also that the Chinese government did not make that distinction when determining its response.) The discussion centered on two questions: In hindsight, was it the right decision? And, if there were a similar situation in Canada, what would the right decision be?

What Do Canadian Millennials Think about the Rest of Asia, Canada, and the United States?

By Erin Williams and Justin Kwan

In the Canadian Millennial Views on Asia survey, 656 participants were asked what words they most associate with specific Asian countries’ government, people, and position in the world. Participants were also asked to choose descriptive words for Canada and the US for the same categories. Respondents were given a list of eleven to fifty words for each category (see below). The table presents the top two responses for each category.

In the focus groups and class discussions, views of China were consistent with what was found in the survey, along with an emphasis on economic issues. Japan and South Korea were seen through the lens of culture/pop culture and were generally well-liked. One surprise was how little India showed up in these discussions, especially given its size and future role in the world.

Question: Please select ONE word that best describes your impression of the following countries regarding their government/people/position in the world.

| Country | Government | People | Position in the World |

| Canada | Liberal

Respecting of Rights |

Friendly

Admired |

Stable

Cooperative/Leading |

| China | Authoritarian

Repressive |

Hardworking

Traditional |

Rising

Strong |

| India | Corrupt

Dysfunctional |

Poor

Traditional |

Rising

Moderate |

| Japan | Well-Functioning

Conservative |

Hardworking

Traditional |

Stable

Strong |

| Philippines | Authoritarian

Corrupt |

Hardworking

Poor |

Unstable

Weak |

| South Korea | Democratic

Well-Functioning |

Hardworking

Traditional |

Stable

Cooperative |

| United States | Dysfunctional

Corrupt |

Arrogant

Friendly |

Declining

Unstable |

For more detailed results, please see https://tinyurl.com/y82zwa67, 18–24.

NOTES

1. Choices: Democratic, authoritarian, respecting of rights, repressive, corrupt, honest, accountable,

unaccountable, dysfunctional, well-functioning, liberal, conservative.

2. Choices: Friendly, unfriendly, humble, arrogant, poor, rich, exciting, boring, honest, dishonest, admired,

disliked, hardworking, religious, traditional.

3. Choices: Stable, unstable, strong, weak, moderate, rising, declining, threatening, cooperative, leading,

following.

The answers revealed a considerable amount of ambivalence. Many supported the Nobel Committee’s decision, but found it difficult to accept that part of the population (people working in the salmon industry) suffered economically. Several participants coalesced around a kind of split-the-difference answer: it is important to stand up for your values, but only if you can afford to absorb the economic blow. In this case, they viewed Norway as being able to afford it, but did not view Canada that way. As several participants explained, “[It was the] right decision for Norway, not the right decision for Canada.”

The aforementioned Abacus report on Canadian youth sheds light on this heightened sensitivity to the potential economic consequences of pursuing values-oriented diplomacy; according to Abacus’s research, a large majority of Canadian youth are impacted negatively by rising prices for housing, food, and tuition. At the same time, there is a palpable concern among members of this age cohort about jobs and the ability to save enough for their futures.4 Thus, it may be the case that these concerns factor heavily into gauging whether Canada should sacrifice its economic relationship with China for the sake of standing up for values. Finally, to add more Canadian context to the values–economy debate, members of one of the focus groups viewed a video of a 2016 press conference in Canada featuring China’s foreign minister and Canada’s then-foreign minister. During the press conference, the Chinese foreign minister responds critically to a question from the Canadian media about human rights in China.5 After viewing the video, focus group members were asked what they felt an appropriate Canadian response would be. They felt it would be appropriate to remind the Chinese foreign minister that the role of the media in Canada is to ask such questions openly. However, they also felt that any Canadian response had to take into account the need to maintain a positive relationship with this much larger and very economically important country.

CANADA’S INTERNAL CHARACTER = CANADA’S FOREIGN POLICY

For comparison purposes, focus group and discussion participants were asked what words came to mind when they heard the word “Canada,” and when they thought about Canada’s foreign policy and its position in the world. Here, there was an interesting conflation of Canada’s internal character and its foreign policy. A large number of participants described Canada in terms of being a diverse, tolerant, and multicultural society. When asked about Canada’s foreign policy, the discussion often returned to this same theme. Given the nationalist and anti-immigrant sentiment rippling through so many of its comparative societies, young millennials saw Canada’s most distinct role in the world as being the best possible role model of a progressive, tolerant, and diverse society. This finding also surfaced in another recent survey of Canadian views on the world and Canada’s foreign affairs.6

Something we flagged for future discussion was whether Asian societies admire and respect these same qualities about Canada. The question is not merely academic: as noted above, the current liberal government is pursuing a “progressive” trade agenda. This means incorporating into formal diplomatic relations things that have been identified as critically important to young Canadians, such as support for LGBTQI rights and a “feminist foreign policy.”

IDEAS FOR CLASSROOM USE

For the two class discussions, we used a shorter and simplified version of the survey questions as a tool for stimulating discussion. To avoid influencing students’ answers, we provided only a minimal overview prior to launching into the focus group questions. We told participants that we were interested in their first-reaction answers and that the questions were not a test of knowledge about Asia, but rather a way to gauge overall impressions. We also laid out some ground rules: (1) there are no right or wrong answers; (2) in small groups, everyone should weigh in on each of the questions; (3) all group members should listen without judgment; and (4) what is said in the room stays in the room.

For Part 1 of the discussion, we distributed a sheet of paper to each participant. On one side was the question asked in Figure 4 (regarding what Canada should prioritize in its relationships with other countries). We asked participants to read through it no more than twice before answering. Then, we asked participants to flip the paper to the other (blank) side and divide the page into four quadrants numbered 1–4. Then, we read out the following questions, giving them no more than forty-five seconds to answer each one: (1) When you hear the word “Asia,” what country or territory comes to mind first? (2) What two words do you most associate with the country or territory you wrote down for the first question? (3) What two words do you most associate with Canada? and (4) What two words do you most associate with Canada’s foreign policy and its position in the world?

Afterward, we asked them to work in groups of four to five, going through each of the questions. Each person was asked to share their answers and provide a bit of explanation for why they named the country or associated words they chose. After about fifteen minutes in small groups, we reconvened to share answers. Although this was a repeat of the small group exercise, we nonetheless found that the students were very interested in listening to and comparing each other’s answers.

An optional Part 2 would be to select case studies. In our classes, one of the cases we used was the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize. We asked students to reflect on whether they thought the Nobel Committee made the right decision and whether, hypothetically, Canada should do the same. The procedure was similar: answer individually, share in small groups, and then discuss as a whole group. Because the participants were not familiar with the case (most were in high school when it happened), this required a short description prior to discussion.

What added an element of motivation to this exercise was telling participants that we planned to compile, analyze, and present the results of the discussions in a final output that would be shared publicly. In our case, we produced a podcast episode featuring interviews with students from one of the focus groups (the episode is available at www.asiapacific.ca/podcast).7 This podcast episode was also broadcast on the campus radio stations of the featured students. Other output ideas are to produce a blog series or share in a subsequent class a summation of views so that individual students can see how their own views compare with those of their peers. ■

NOTES

- The survey and analytical report were conducted by Dr. Yushu Zhu, responsible for APF Canada’s work on surveys and data.

- David Coletto, “The Next Canada: Politics, Political Engagement, and Priorities of Canada’s Next Electoral Powerhouse: Young Canadians,” Abacus Data, April 19, 2016, 3–4. Report commissioned by the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations. Available at https://tinyurl.com/jvykber.

- Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, “2018 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Asia,” June 2018, 22, 27. Available at https://tinyurl.com/y9j5rd82.

- Colletto, 4.

- CBC News, “China’s Foreign Minister Criticizes Canadian Reporter for Her Question,” YouTube video, 2:59, June 2, 2016, https://tinyurl.com/y9o7v2gq.

- “Canada’s World Survey 2018,” Environics Institute, April 2018, https://tinyurl.com/ y946zqg4.

- The podcast episode, titled “The Youth Element: Talking Asia with Canadian Millennials,” is available in iTunes and Google Play, and at https://tinyurl.com/yabekdql.