For the past five years, I’ve been screening Frank Capra’s controversial Know Your Enemy: Japan (1945) in survey courses and upper-division seminars. Stunning edits, provocative footage, and a brilliant soundtrack make this last of the U.S. Army’s Why We Fight series a truly arresting documentary. To warn Americans that defeating Japan would require the nation’s utmost effort, Capra spliced together hundreds of menacing, exoticizing shots of festivals, parades, assembly lines, sporting events, funerals, military parades, battlefields, and police raids, skillfully culled from Japanese cinematic and documentary footage. Superimposed over these images are a number of theories about Japan’s national character and the origins of the Pacific War. Because Capra’s film traffics in dated racist imagery and derogatory stereotypes, I initially showed it to serve as an example of American wartime propaganda, as a window into the U.S. psyche circa 1945.1 These days; however, I have become less enthusiastic about dismissing Know Your Enemy as a mere artifact of an older, less tolerant era. Not only have recent scholarship and a resurgent public interest in the Pacific War converged to give elements of Capra’s documentary an oddly contemporary feel, but more importantly, much of the information imparted in Know Your Enemy can be used to set up a more serious study of prewar Japanese history. Therefore, instead of just exposing the film’s logical contradictions and untenable generalizations (which is necessary but not sufficient), I’ve begun to use Know Your Enemy to engage two resilient controversies in Japanese historiography: Hirohito’s war responsibility and the nature of the “road to Pearl Harbor.”

CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH

OR MILITARY COMMANDER?

The Biography Series (1962)

According to Know Your Enemy, the Sh¬wa emperor was a central figure in Japan’s wars against China and the United States. As the mounted Hirohito reviews thousands of soldiers shouting, “Banzai!” the narrator refers to him as a Shinto-corrupting “diabolical joker” whose secular and spiritual authority exceeds the combined power of the Pope, Stalin, Truman, the Orthodox Patriarch, and Churchill. In Capra’s account, the Japanese soldier is to be feared because his life’s goal is to die in battle, become interred at the Yasukuni shrine, and earn the august emperor’s obeisance as a fellow god. There is some prevarication in the film about the imperial institution’s ancient links to militarism, but it does portray Hirohito as a generalissimo, a view that became largely discredited after World War II.

As the mounted Hirohito reviews thousands of soldiers shouting, “Banzai!,” the narrator refers to him as a Shint¯o-corrupting “diabolical joker” whose secular and spiritual authority exceed the combined power of the Pope, Stalin, Truman, the Orthodox Patriarch, and Churchill.

To show students an alternative American-manufactured view of Japan and the emperor, I screen Emperor Hirohito (1962), part of Coronet Films’ The Biography Series. Unlike Know Your Enemy, the Coronet biography was released during a high point in Japanese-American relations, after the anti-Security Treaty demonstrations of 1960 and before the commitment of U.S. ground forces in Vietnam. Coronet’s enclosed “discussion guide” provides a good synopsis of the idiom Carol Gluck has dubbed “The Good Showa Emperor”:2. . . born a prisoner of Japanese feudal tradition that considered him a living god, [Hirohito] was finally freed to use his influence for democratic reform. He starts on a goodwill tour of Europe at the age of twenty-one. Impressed by Western customs and Britain’s constitutional monarchy, he wishes to model his reign along democratic lines. But fanatic Japanese militarists oppose liberalism and plan expansion by conquest. . . . When Japan is defeated and the Allied occupation begins, the war leaders are executed and the emperor . . . becomes a constitutional monarch, a symbol of peace and stability for the new Japan. . . . The emperor thus realizes the democratizing role he had envisioned twenty-five years before.3

The contrasting treatments of the Showa emperor in these two films is striking, mirroring the divided English-language historiography on Hirohito’s role in the Pacific War. The Coronet film privileges footage of the young crown prince playing golf, riding in an automobile, and embracing “The West,” while the Capra film is packed with images of emperor worship and Shint¬ ritual. Both films use identical footage of Hirohito on his white horse: Capra, to illustrate his martial leadership, and Coronet, to show the captive young monarch participating in activities he found distasteful.

Based on my reading of Stephen S. Large’s well-received and solidly researched Emperor Hirohito and Sh¬wa Japan: A Political Biography (1991), I once considered the Coronet film to be more in step with modern scholarship than Capra’s Know Your Enemy. Large’s book argues that Hirohito scrupulously adhered to the constitutional monarch ideal as he and his advisors understood it, with rare exceptions approving all cabinet decisions pro forma while restraining himself from contravening civil or military leaders on policy. Large’s Hirohito, though more flawed and complex and certainly not democratic, resembles the captive, reluctant figurehead portrayed in the Coronet film.4

The Young Hirohito. (K. K. Kyodo News)

A decade later, in Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (2000), Herbert P. Bix argues that the image of the “captive” and “passive” Hirohito is a fabrication of postwar U.S. and Japanese political propaganda. One of the many points of disagreement between the two historians rests on the credibility of the so-called “Monologue,” a 1946 deposition in which Hirohito explains (or obfuscates) his role in the events leading up to and including the Pacific War. Large entertains the notion that the Monologue (published in Japan in 1990 after languishing in an interpreter’s basement for some four decades) is opportunistic special pleading but finds the crux of Hirohito’s “defense,” that he could do nothing to prevent war between the U.S. and Japan, corroborated in the wartime diaries of court advisors and other Hirohito intimates. Bix opens his Pulitzer-Prize-winning book by characterizing the Monologue as a whitewash, a symbol “of the secrecy, myth, and gross misrepresentation that surrounded his entire life (1–3).”5 Bix argues that especially after the Imperial Headquarters was established in late 1937, the Sh¬wa emperor became a real commander-in-chief (327–30).

In light of Bix’s book, Capra’s editorial standpoint on the emperor begins to look less dated. Like the Coronet film, both Bix and Large make much of the young regent Hirohito’s 1921 trip to England. Large considered Hirohito’s meeting with King George V a formative experience, one where he observed firsthand the principle of imperial restraint embodied in the English constitution (21–3). Conversely, Bix’s biography argues for a different type of Georgian influence:

. . . the real image George conveyed was that of an activist monarch who judged the qualifications of candidates for prime minister and exercised his considerable political power behind the scenes . . .

To the extent that George V strengthened Hirohito in the belief that an emperor should have his own political judgments independent of his ministers, George’s “lessons” had nothing to do with “constitutional monarchy” (117–8).

The pattern repeats throughout the two books: the emperor’s connection to the same important events is discussed (The Chang Tso-lin Incident, the Manchurian Incident, the February 26 Incident, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, Pearl Harbor, the Surrender) as parts of different historical briefs; one for an active generalissimo, the other for a British-style constitutional monarch. A thorough discussion of every disagreement between Large and Bix might make a good graduate seminar. For my purposes, getting undergraduates to think about documentary film and propaganda in relation to trends in historiography, a more selective approach is appropriate. Before screening either film, I assign the following readings and questions to familiarize students with the debates surrounding the Showa emperor and the wars of the 1930s and 1940s.

READINGS (about 225 pages total)

Large, Stephen S. Emperor Hirohito and Sh¬wa Japan: A Political Biography, pp. 1–32; _______. “Emperor Hirohito and Early Showa Japan.” Monumenta Nipponica 46, no. 3 (1991): 349–68.

_______. Review of Hirohito: Behind the Myth, by Edward Behr. Journal of Japanese Studies 17, no. 2 (1991): 508–12.

Bix, Herbert P. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, pp. 1–123. _______. “The Showa Emperor’s ‘Monologue’ and the Problem of War Responsibility.” Journal of Japanese Studies 18, no. 2 (1992): 334–63.

“Constitution of the Empire of Japan.” In Japan Emerges: A Concise History of Japan from Its Origin to the Present, ed. Steven Warshaw, 203–12. Berkeley: Diablo Press, 1993.

Questions

1. According to Large and Bix, why is the Sh¬wa emperor a controversial figure?

2. According to Large and Bix, who were the most important influences on Hirohito before he ascended to the throne, and what impact did Hirohito’s youth have upon the issue of war responsibility?

3. Under the Meiji constitution, what war-making powers are reserved for the emperor? What constraints are placed upon this power?

4. What major differences separate Bix’s and Large’s interpretations of “constitutional monarchy” and the emperor’s ability to influence the course of events?

Students unfailingly attach Large to the Coronet film, and Bix to Capra’s: in short, they develop a vocabulary for discussing broad lines of interpretation in modern Japanese history, “Cold War consensus” and “revisionist/pre surrender” frameworks.

On the due date of the essays, I divide students into opposing sides to discuss Hirohito’s war responsibility. This discussion centers around Hirohito’s conceptions of his own historical mission, how much foreknowledge he had of major offensives like Pearl Harbor, his ability to influence the decisions ratified at Imperial Conferences, the interpretation of his famous “monologue,” and how we define “responsibility.” In the lesson following the debate, we view the Capra and Coronet films; this takes two classroom periods. In their follow-up questions to the films, I ask class members to consider each film’s portrayal of the emperor in light of the Large/Bix readings. Students unfailingly attach Large to the Coronet film, and Bix to Capra’s; in short, they develop a vocabulary for discussing broad lines of interpretation in modern Japanese history, “Cold War consensus” and “revisionist/presurrender” frameworks. In my concluding remarks, I stress that Bix does not consider the Showa emperor to have been a dictator (like Capra) and that Large does not consider him to have been a latent democrat (like the Coronet film). And unlike the documentary/propaganda filmmakers, the two historians acknowledge the difficulty of ascertaining the facts of the matter, due to the paucity of thorough documentation on the emperor’s activities. Much of this difficulty arises from the inviolability of the sacred Japanese throne, both for the U.S. authorities who stifled investigation of these issues during the occupation, and for the Imperial Household Agency, which has obstructed access to important imperial diaries and documents. This problem of opacity leads me to ask students to consider the costs democracies must pay for the putative benefits of “symbolic” emperors and constitutional monarchies.

THE ROAD TO PEARL HARBOR

Much of the historical component of Know Your Enemy: Japan identifies the so-called Tanaka Plan as the Japanese state’s blueprint for aggression. Named for a phantom 1927 memorial allegedly penned by Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi for the Showa emperor, it was first published in Chinese newspapers in 1929. The “original” has never been located, and on internal evidence, circulated English and Chinese translations appear to be forgeries. Since subsequent actions by the Japanese state and military conformed loosely to sections of Tanaka’s “memorial,” which called for the successive conquests of Manchuria, China, and Southeast Asia, it became a widely disseminated explanation, a “smoking gun,” for publicists and scholars who saw Japanese aggression from 1931 to 1945 as part of one big imperial conspiracy. While Herbert Bix has pulled off a remarkable achievement in his brief against the mythical “Good Showa Emperor,” and is mindful of historical dynamics, his argument about the centrality of the monarchy to twentieth-century Japan and the war effort lends itself to monocausal interpretations with a family resemblance to the old “Tanaka Plan.” I fear that the high sales and effusive journalistic acclaim of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, on the heels of Iris Chang’s popular Rape of Nanking, signals a return to a simpler time, when one could dismiss the twists and turns in Japan’s historical path between 1868 and 1937. Attributing Japan’s post-1931 “go-fast imperialism” to a unified vision of world conquest, Japanese national character traits, or the machinations of a Japanese court bent on strengthening the imperial institution, ignores too much of the social history and international context that bore upon even the most ill-informed foreign-policy decisions.

I fear that the high sales and effusive journalistic acclaim of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, on the heels of Iris Chang’s popular Rape of Nanking, signals a return to a simpler time, when one could dismiss the twists and turns in Japan’s historical path between 1868 and 1937.

In many respects, post-war English-language historiography on early Showa foreign policy has been a response to Capra’s and similar narratives of Japan’s “road to Pearl Harbor.” Therefore, as it has done for historians, Know Your Enemy gives students an easy-tograsp and ideologically potent framework from which to begin serious study of the period and its dynamics. Based on Know Your Enemy, I ask students to answer the following questions: When did the Japanese polity and military embark on the road to the Pacific War? Why did Japanese leaders and citizens wage war against China and the United States? What were the objectives of Japanese diplomacy in the 1920s and 1930s?

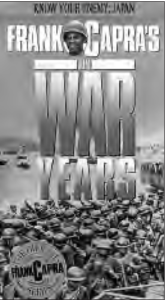

The film’s screenwriters locate the problem in the Meiji state’s corruption of Shint¬, the dominance of military and corporate elites in government, and the messianic vision of leaders like Tanaka Giichi and “secret organizations” like the Amur River Society. On the one hand, the film proffers the notion that the Japanese populace had been coerced, tricked, or hypnotized by its leaders. The Japanese are characterized as “photographic prints off the same negative.” On the other hand, the film undermines its own assertions of unthinking conformity by depicting an elaborate apparatus of terror and police statism that suppresses dissent. The extent of this dissent is not discussed, which raises questions about the relationship between state and society during the war. Teachers can contrast the points made in the documentary with the following scholarly resources, not only as a corrective, but also to contrast the historian’s craft to that of the propagandist.

READINGS (about 425 pages total)

Stephan, John J. “The Tanaka Memorial, 1927: Authentic or Spurious?” Modern Asian Studies 7, 4 (1973): 733–45. This article succinctly documents the first public appearances of the memorial, traces its path to world notoriety, and makes a strong case for its spuriousness.

Wray, Harry, and Hilary Conroy, eds. Japan Examined: Perspectives on Modern Japanese History. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983, pp. 237–330. The essays in this volume are aimed at undergraduates, with emphases on points of historiographical contention and persuasive writing. Parts IX and X, titled “The 1930s: Aberration or Logical Outcome?” and “Japan’s Foreign Policy in the 1930s: Search for Autonomy or Naked Aggression?” contain essays by leading Japanese and U.S. historians on the cultural, social, diplomatic, economic, and political history of 1930s Japan.

Young, Louise. Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, pp. 115–80. In chapter 3, “War Fever,” Young describes the effects of the Manchurian Incident (September 18, 1931) upon Japanese journalism, music, and popular culture. She argues that jingoistic media in the early 1930s was not a product of censorship or state orchestration: there was significant public sentiment in Japan for anti-Westernism and empire in China, which created commercial incentives for jingoism not unlike the infamous yellow journalism in U.S. history.

Duus, Peter. “Introduction, Japan’s Wartime Empire: Problems and Issues.” In The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931–1945, ed. Peter Duus et. al., xi–xlvii. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. Duus’s essay describes the changed character of Japanese colonialism in the 1930s. Meiji expansion was cautious, conducted within “international norms,” and used cost-benefit analysis. Sh¬wa expansion was the creature of different world conditions, a different generation of leadership, and was self-defeating from its very inception.

. . . the good propaganda films work because they are not laughable: much of what is said in Capra’s film was based on the best knowledge available at the time. The art is in omission, emphasis, and style, not necessarily in telling big lies.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Cook, Haruko Taya, and Theodore F. Cook. Japan at War: An Oral History. New York: The New Press, 1992, pp. 47–94. For this unit, sections 2 and 3 are most pertinent, showing that some Japanese hated the war and were silenced by the government while others believed in the war for reasons ranging from the benefits accruing to factory workers to the belief that the Japanese were rolling back Western imperialism in Asia.

Lu, David John, ed. Sources of Japanese History, Vol. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1974. pp. 129–79. Chapter XIV, “Rise of Ultra-Nationalism and the Pacific War,” contains translations of the major policy documents leading to war and includes student and “housewife” testimonies of Japanese life during wartime in the sections “Students at War” and “Life in Wartime Tokyo.”

Minear, Richard H., ed. Through Japanese Eyes, Vol. 1. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974, pp. 97–113. “Ichiro’s Diary” is excerpted correspondence from a teenage boy and his mother dated May, 1944 to August, 1945; it captures the devastating effects of the war on Japanese civilians and Ichir¬’s oscillating moods and impressions as Japan’s prospects darkened.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. Showa: An Inside History of Hirohito’s Japan. New York: Schocken Books, 1984, pp. 94–183. Part II, “Coming of Age—1941–1945” is an extensive treatment of three lives on the homefront and battlefield, including both flights of Japanese patriotic pride and depths of disbelief at the hubris of attacking America. Like the testimonies from the Cook, Minear, and Lu sourcebooks, the Morris-Suzuki sections highlight the wartime divisions of Japanese wartime opinion even at the household level.

QUESTIONS

1. Which Japan Examined essays agree with the general explanatory framework and/or chronology of the Capra film? Which of Japan Examined essays contradict this narrative, and on what specific points?

2. Based on the Duus and Young selections, explain why 1931 was such an important watershed in Japanese history.

3. According to Hata Ikuhiko, what is implied by the phrase “Fifteen Year War”? What is his criticism of this appellation?

4. Based on the oral history readings, answer the following questions with reference to specific examples: Was wartime Japan a police state? Did the people actively support their government in the prosecution of the war? Identify and describe the sources of conflict over wartime policies between Japanese: urbanites and farmers; elders and youth; university students and workers; citizens and officials.

5. Based on your understanding of the selections from David Lu’s sourcebook and the essays by Wray, Barnhart, and Yoji, list Japanese motivations and justifications for fighting the United States not considered in the Capra film.

WHAT MAKES PROPAGANDA WORK?

Juxtaposing propagandistic documentaries with serious academic debates illustrates a couple of important points. First, good propaganda films work because they are not laughable: much of what is said in Capra’s film was based on the best knowledge available at the time. The art is in omission, emphasis, and style, not necessarily in telling big lies. The other lesson is that historiography does not always move in a linear direction, approaching consensus as more data pours in. This is not to say that all opinions are equally valid. We can say, based on copious documentation, that while the Japanese of the 1930s and 1940s were not a homogenous people, “100 million hearts beating in unison”—neither were they passive victims led blindly into war. Japanese statesmen and activists were fully enmeshed in the diplomacy, economy, and cultures of global modernity; theirs was not an “Asian variant” of the colonial motif. Meiji and Sh¬wa foreign policy show marked discontinuity and should be studied accordingly. In a word, the study of Japanese history requires as much patience, determination, and sophistication as the study of any other modern human community.

FILMOGRAPHY

Frank Capra’s the War Years, “Know Your Enemy: Japan.” RCA/Columbia Pictures Home Video, 1990. Black & White, approx. 62 minutes. Emperor Hirohito: The Biography Series. Coronet Film & Video, 1962, 1963. Black & White, 25:45.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reviews and Interviews

Buruma, Ian. “The Emperor’s Secrets,” review of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert Bix. The New York Review of Books, March 29, 2001, 24–8. French, Howard W. “Out From the Shadows of the Imperial Mystique (Interview with Herbert Bix).” New York Times, September 12, 2000, Books Section.

Fujitani Takashi. Review of Emperor Hirohito and Showa Japan: A Political Biography, by Stephen S. Large. Journal of Asian Studies 53, no. 1 (1994): 218–9.

Gluck, Carol. “Puppet on His Own String,” review of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P. Bix. Times Literary Supplement, November 10, 2000, 3–5. Havens, Thomas. Review of Emperor Hirohito and Showa Japan: A Political Biography, by Stephen S. Large. American Historical Review 99, no. 1 (1994): 285.

Iriye, Akira. “Interpreting Hirohito,” review of Emperor Hirohito and Showa Japan: A Political Biography, by Stephen S. Large. Journal of Japanese Studies 20, no. 2 (1994): 542–7.

Large, Stephen S. “Emperor Hirohito and Early Showa Japan,” review of Showa Tenno dokuhaku hachijikan, Makino Nobuaki Nikki, Nara Takeji jiju bukancho nikki and Tojo Naikaku Soridaijin kimitsu kiroku, various authors. Monumenta Nipponica 46, no. 3 (1991): 349–68.

Large, Stephen S. Review of Hirohito: Behind the Myth, by Edward Behr. Journal of Japanese Studies 17, no. 2 (1991): 508–12.

Margolies, Jacob. “Bix’s Pulitzer Prize-Winning ‘Hirohito’ Challenges Readers to “Confront Facts” (Interview with Herbert Bix). The Daily Yomiuri, May 13, 2001. Spector, Ronald. “The Chrysanthemum Throne,” review of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P. Bix. New York Times, November 19, 2000, sec. 7. Titus, David A. Review of Emperor Hirohito and Showa Japan: A Political Biography, by Stephen S. Large. Monumenta Nipponica 48, no. 1 (1993): 127–30.

Wintel, Justin. “An Ineffective Constitutional Monarch? Or a Key Player in Japan’s Brutal Imperialist Policies?,” review of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P. Bix. Sunday Times, May 18, 2001, Features.

Showa History

“Constitution of the Empire of Japan.” In Japan Emerges: A Concise History of Japan from its Origin to the Present, ed. Steven Warshaw, 203–12. Berkeley: Diablo Press, 1993.

Bix, Herbert P. “The Showa Emperor’s ‘Monologue’ and the Problem of War Responsibility.” Journal of Japanese Studies 18, no. 2 (1992): 295–365. _______. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: Harper Collins, 2000.

Coox, Alvin D. “The Pacific War.” In The Cambridge History of Japan: The Twentieth Century, ed. Peter Duus, 6, 315–82. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Duus, Peter. “Introduction, Japan’s Wartime Empire: Problems and Issues.” In The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931–1945, ed. Peter Duus, Ramon Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, xi–xlvii. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Field, Norma. In the Realm of a Dying Emperor: Japan at Century’s End. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

Gluck, Carol. “Introduction.” In Showa: The Japan of Hirohito, ed. Carol Gluck and Stephen R. Graubard, xi–lxii. New York: W. W. Norton, 1992.

Hata, Ikuhiko. “Continental Expansion, 1905–1941.” In The Cambridge History of Japan: The Twentieth Century, ed. Peter Duus, 6, 271–314. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Havens, Thomas R. Valley of Darkness: The Japanese People and World War Two. New York: W. W. Norton, 1978.

Ienaga Saburo. The Pacific War, 1931–1945: A Critical Perspective on Japan’s Role in World War II by a Leading Japanese Scholar. Translated by Frank Baldwin. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Iriye, Akira. Across the Pacific: An Inner History of American-East Asian Relations. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., 1967.

_______. After Imperialism: The Search for a New Order in the Far East, 1921–1931. New York: Atheneum, 1969.

Large, Stephen S. Emperor Hirohito and Sh¬wa Japan: A Political Biography. London: Routledge, 1992.

Stephan, John J. “The Tanaka Memorial, 1927: Authentic or Spurious?” Modern Asian Studies 7, no. 4 (1973): 733–45.

Tipton, Elise. Japanese Police State: Tokko in Interwar Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990.

Wilson, George M., ed. Crisis Politics in Prewar Japan: Institutional and Ideological Problems of the 1930s, Monumenta Nipponica Monograph Series. Tokyo: Sophia University, 1970.

Wray, Harry, and Hilary Conroy, eds. Japan Examined: Perspectives on Modern Japanese History. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983.

Young, Louise. Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

NOTES

1. John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986), pp. 18–22.

2. Carol Gluck, “Introduction,” in Sh¬wa: The Japan of Hirohito, ed. Carol Gluck and Stephen R. Graubard (New York: W. W. Norton, 1992), xix–xx.

3. Discussion Guide, Emperor Hirohito: The Biography Series (Deerfield, Ill.: Coronet Films, 1962), Video Cassette.

4. In fact, two highly respected historians of modern Japan have appraised Large’s account as consonant with postwar orthodoxy. See: Fujitani Takashi, review of Emperor Hirohito and Sh¬wa Japan: A Political Biography, by Stephen S. Large, Journal of Asian Studies 53, no. 1 (1994): 218–9; Thomas Havens, review of Emperor Hirohito and Sh¬wa Japan: A Political Biography, by Stephen S. Large, American Historical Review 99, no. 1 (1994): 285.

5. See the following two articles for different interpretations of the significance and reliability of the Monologue: Stephen S. Large, “Emperor Hirohito and Early Sh¬wa Japan,” Monumenta Nipponica 46, no. 3 (1991): 349–68, and Herbert P. Bix, “The Sh¬wa Emperor’s ‘Monologue’ and the Problem of War Responsibility,” Journal of Japanese Studies 18, no. 2 (1992): 295–365.