We know only a few things about the coal collector who eked out an existence in Osaka’s slum neighborhoods early in the 1900s. He had a twenty-four-year-old wife, a three-year-old son, and wages of ¥12 or ¥13 a month—about half of what a railway conductor made, and a third as much as an ironworker. We know too that these wages barely covered food, housing, and rented bedding, leaving the family dependent for everything else on the ¥2 his wife made each month making straw sandals.1 The government records tell us nothing about the man’s name, his social life, or how he survived on so little. They do, however, provide one additional scrap of information, and it is important. He was a migrant to the city, born on a farm on Japan’s Kii peninsula, then taken to Osaka after his mother died in the 1880s.

The importance of that additional fact lies in the evidence it presents of something that became increasingly obvious to me across the last dozen years, as I pored over material on the daily lives of hinmin, or poor people, during the last half of Japan’s Meiji era (1868–1912). Setting out on the study, I thought of poverty simply as poverty. Impoverished people were poor; they had trouble putting food on the table; life was cruel. As I read the accounts of journalists, statisticians, and poor people themselves, however, I discovered something I should have known: poverty is as nuanced and variegated as the people who experience it, and one of the biggest factors in determining its nuances was whether people lived in the city or in the village.

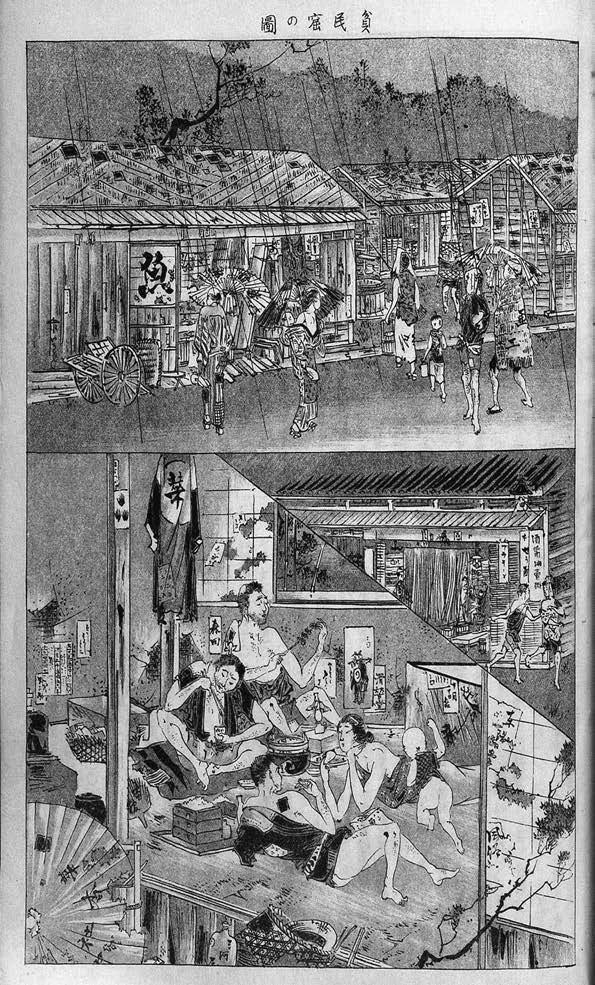

Before looking at the differences between urban and rural hardship in the late Meiji years, it is essential to note two or three general features of poverty then. The first was that being poor was not unusual. Scholars have determined that as many as 60 percent of all Japanese—more than twenty-five million people—were poor in the late 1800s and that one of every six or seven city-dwellers was desperately poor.2 The second feature—illustrated by our young coal collector’s move to Osaka—was that the general understanding of poverty then was different from what it had been in the late Tokugawa years, mainly because of the way in which Japan was modernizing. Although economic hardship was widespread in the Tokugawa period (1600–1868), the country was still preindustrial, and, in the public view, poverty was primarily rural, a result of farmers’ unfortunate personal choices or of fate. Even when commercial farming spread across the country in the late Tokugawa years, spawning proto-industrial businesses such as a network of Hokkaido enterprises that processed and marketed herring meal fertilizer, the general understanding of poverty changed only marginally, because there were no capitalist industries to fundamentally alter the urban–rural balance.3 But two things changed that in the early Meiji years. First, the government’s pro-industry policies spawned factories in the cities. Second, a deflation-induced national depression swept Japan’s rural regions like a typhoon in the 1880s, causing hundreds of thousands of farmers to lose their land and prompting food-starved villagers to send their children to the cities for work, just as the coal collector’s family did. The result was a massive domestic migration from farms to cities and an explosion of urban populations, with Tokyo nearly tripling in size by the early 1900s, Osaka and Kyoto nearly doubling. In the cities, these newcomers settled in ugly, crowded areas that journalists labeled hinminkutsu (“caverns of the poor,” usually translated as “slums”) and commentators began worrying about an urban shakai mondai (“social problem”). As a result, hinkon, or poverty, came to be seen more and more as an urban phenomenon, one of “the social consequences of industrial development.”4

A third general feature that bears note before the essay takes up the differences between urban and rural poverty is that poor people everywhere shared many things, including that most obvious universal: an often-desperate lack of money. In villages and cities alike, poor people had only enough means to put skimpy food on the table, even in the best of times; they had to take out loans (usually at exorbitant interest rates) or pawn clothing in harder periods. Regarding city-dwellers generally, the pioneering poverty journalist Matsubara Iwagorō (1866–1935) wrote in the 1890s that the most important lesson in the hindaigaku (“college of the poor”) was “how to make do for so many on so little.” Poverty, he observed, “keeps a terrible school; one must graduate with honors from it or die.”5 About impoverished villagers, the novelist and farmer Nagatsuka Takashi (1879–1915) said it was common for food to become so scarce in winter that the residents “ate anything, however unsavory it looked or smelled, just to fill the gaping void they felt inside them.”6

Impoverished people everywhere also shared the characteristic of working harder than most other people. Middle-class pundits sneered that the poor “will work no more than they absolutely must” or that most poor people “do not work because they are lazy,”7 but evidence argued otherwise. Take working hours. A 1903 government survey of factory workers found twelve-hour shifts to be the norm, while a 1904 study of varied occupations showed that most hinmin had ten- or twelve-hour days (train conductors worked sixteen-hour days!), and they worked six days a week.8 Employers also required overtime work frequently, usually without higher pay. Nothing provided more dramatic evidence of how hard they worked than the fact that everyone in the slum family, including children as young as ten, had to work for pay if the family were to survive. Wives did piecework at home or, in more cases than officials acknowledged, sex work in the evening; boys served as shop assistants; daughters toiled in textile factories or waited tables. And the pattern repeated itself in every poor village household. While the winter months provided some respite, the other seasons found everyone in the fields from early morning until nightfall. Harvest time was worst; as one Hiroshima native recalled: “Usually we worked until twelve o-clock, one o-clock, or two o-clock in the morning. By the time we went to take a bath, the water would be cold . . . We’d have to start again early in the morning.”9 And women worked even harder than men, spending hours in the fields each day in addition to rearing children, tending house, cooking, and engaging in side jobs to earn additional money. Mothers carried infants on their backs as they weeded rice fields.

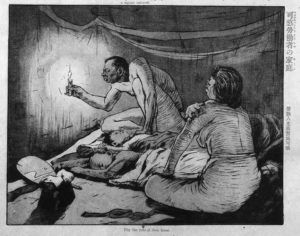

The hard work and inadequate income also rendered both village and urban poor vulnerable to crises. Tired and undernourished bodies were prone to illness, and when sickness came, the hinmin lacked resources to fight it off. In the villages, a lack of educated doctors was a problem, while in the cities, slum-dwellers were treated as dispensable when epidemics hit. If the problem was cholera, officials regularly sent the poor to quarantine hospitals, popularly called “dump sites,” where they were left to die, and impoverished workers who contracted tuberculosis often were fired so that they would not infect other laborers. Stories abounded of fired laborers who had no choice but to return to the village, where they infected relatives and friends; one returnee reportedly caused the deaths of thirty people in a single village of 200. According to a popular saying: “The rich recover from tuberculosis, but the poor do not.”10 So too with natural disasters. Slums were located in lowlands especially vulnerable to flooding, and the shabby housing there was prone to fires, while poor villagers lacked buffers against the ravages of droughts and floods.

And the vulnerability was intensified by the discrimination that hinmin everywhere suffered. Hearing themselves described constantly as ignorant rustics, or as “exceedingly deficient in their intellectual faculties,” poor people found it hard not to internalize the condescension. Among those who suffered most from this kind of dehumanization were the burakumin, or outcasts, who for centuries had to live in segregated enclaves, doing “impure” work such as leather tanning and butchering. The outcast category was officially eliminated early in the Meiji era, but in cities and countryside alike, former burakumin had no option but to continue living in their own villages or neighborhoods, where they were despised even by other hinmin, often called “dog eaters” or “savages.”11 That such discrimination affected people’s self-images and ate away at their spiritual resilience is indisputable. Late Meiji newspapers ran endless accounts of people pushed over the precipice by their economic and spiritual vulnerability—like forty-two-year-old musician Miyata Genjirō, who set himself afire in 1900 after rising prices and illness made life unbearable. The story’s caption: “Pressed by poverty, he set his body on fire.”12

A final thing that nearly all poor people shared was somewhat counterintuitive. Wherever one looks, in fishing villages or Osaka rowhouses, the poor attacked life with gusto and ambition. Their public image may have been of downtrodden masses, people who “do not know the joys [kōfuku] of the world,”13 but anyone who actually looked found hinmin throwing themselves into life with as much energy as their affluent peers did. Village accounts were full of cheap noodle places where, in the words of schoolteacher Shimazaki Tōson (1872–1943), “The lowliest laborers, the teamsters, and the poor farmers round about come to have their saké warmed”;14 of families intermingling with rich neighbors at shrine festivals; and of housewives laughing heartily at bawdy jokes. Life was hard, not dull. So too in the city. Hinmin neighborhoods were a cacophony of street life, markets, festivalgoers, and entertainment quarters, with the slum-dwellers participating as actively as anyone—putting away their “oil-stained clothes” of the shop to “stroll through the park in top hat and frockcoat on Sundays.”15 They were politically active, too. They read newspapers in surprisingly high numbers, and they made up the majority of the huge throngs who took to the streets during the last Meiji decade to protest government corruption and rising streetcar fares.

Despite all the things impoverished people shared, however, the evidence makes it clear that poverty did not treat urbanites and villagers alike. The late Meiji accounts reveal striking differences between what farmers and city-dwellers actually experienced, not because they were inherently different kinds of people (indeed, they often were the same people, merely transplanted) but because systemic and demographic conditions rendered the daily experience of impoverishment in the city distinct from what it was in the village.

For one thing, urbanites and villagers did different kinds of work. While rural life supported an array of occupations, the vast majority of people farmed or fished, usually working together as they did it. They cooperated in mending nets, in filling rice paddies with water, in sorting silkworms, in haggling for better rice prices. In the cities, by contrast, modernity created a breathtaking panoply of job types, many of them new in the modern era and just as many of them individualistic in nature. An official list of city jobs in 1898 included no fewer than 358 categories.16 The better-known included factory workers, entertainers, craftsmen, construction workers, and shafu (rickshaw pullers). But the variety was spectacular: night soil collectors, rag pickers, wig makers, day laborers, restaurant waiters, cigarette rollers. The tens of thousands of rickshaw pullers, whose clickety-clack sounds ricocheted off city streets, sometimes were called the quintessential representatives of modern urban work, not just because they were ever-present, but because their jobs were so individualistic, taking them down unknown streets and fostering a rules-be-damned approach to life that would have been anathema in the village. Diversity and individualism showed up even within single households—like the one described in a 1901 issue of the journal Taiyō, where the father was a kozukai (errand man) in Tokyo’s commercial district, the fifteen-year-old son a print shop assistant, the thirteen-year-old daughter a factory girl, and the mother a home-based pieceworker.17 Diverse jobs took family members to different locales each day, rendering impossible the solidarity of village households.

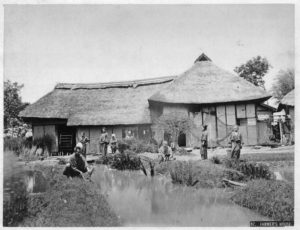

A second difference lay in people’s lodging places. The urban hinmin lived either in one- or two-room nagaya (rowhouse) apartments, usually with less than 100 square feet for a family of three to five; the very poorest stayed in flea-infested flophouses called kichin’yado. Even at era’s end, in 1912, three-quarters of Tokyo’s poor families lived in single-room apartments.18 And their housing stock was grim: flimsy, flammable wooden structures, poorly maintained by unregulated landlords, with the alley behind for washing or cooking. Novelist Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916) described hinmin dwellings, which multiplied “like fleas in the rainy season,” as “monuments to this version of survival of the fittest, in which bottom-feeling capitalists” got rich on “jerry-built housing.”19 In the countryside, by contrast, while tumbledown huts were not unknown, even poor peasants typically had comparatively spacious homes with at least four rooms, including a kitchen, a living room, and two bedrooms. The shoji paper on the petitions dividing rooms might be dirty and holey, and the main quarters likely were dark and smoky from a lack of windows or chimneys, with outdoor toilet smells mingling with the aromas of flowers and trees. Animals often occupied their own quarters at the front of the house, striking Tōson with “the way in which the lives of human beings and of cattle are all blended together.”20 But spacious rural settings allowed even the poorest families to live in houses big enough to haunt the memories of their cousins in the slums.

And those landscapes pointed to a third difference: the impact of nature on the way people experienced hardship. Nature could be cruel in both city and village. Floods, for example, hit hard everywhere, with the great flood of 1910 destroying more than 150,000 buildings in Tokyo’s poorest neighborhoods, while an 1889 flood in the Nara prefectural village of Totsukawa wiped out a third of the homes and forced 2,500 residents to migrate to Hokkaido. Nonetheless, nature generally affected city-dwellers and farmers differently, shaping village life with an intensity unknown in Osaka and Tokyo. If the skies withheld their rains or let too much fall, farmers suffered crop failures, while urbanites merely complained about inconvenience. When winter went on too long, poor farmers’ stocks of buried potatoes and apples gave out and hunger threatened with a ferocity rarely known in the city. In the worst of times, like the Tōhoku famine of 1905, large numbers of farm families (280,000 in Miyage Prefecture alone) starved or were left destitute.

At the same time, nature provided succor and sustenance in the countryside in a way that was denied to city-dwellers. During spring, summer, and autumn, even the poorest farmers could eat wild fruits, mountain plants, and fish that swam in their rivers. In all but the coldest times, rural children had natural places to play and swim. Even when hunger struck—when, to quote the ancient Man’yōshū poet, “In the cauldron, a spider spins its web, with not a grain to cook”—natural settings provided spiritual buffers. As the destitute protagonist Seizō lay dying in the novel Country Teacher by Tayama Katai (1872–1930), he still could write in his journal about how “at night unknown insects would sing their noisy songs, as the frogs also did,” while naming fifty-odd flowers that he observed in the fields around him. Even when pantries became bare in winter, the white vistas gave shivering teacher Tōson an “almost piercing sense of joy.”21 Nature never made poverty easy, but it moderated its pangs.

A fourth variant that affected the feel of poverty lay in the quality of rural and urban human interactions. It can be argued that nothing made economic hardship harder to bear in the slums than the absence of the hamlet’s womb-like community life. Villages were ancient organisms, bound together by customs and connections nurtured across generations. Rice was planted communally; water was shared; abalone divers along the Inland Sea swam together, breastfed their babies together, and chatted like members of a family.22 Like their city cousins, villagers flocked to the temples and shrines for festival merrymaking, but unlike those cousins, they knew the other revelers personally. The norms that governed villages were confining and sexist, dictating who could bathe where and when, what one should wear, which sex practices were acceptable for boys and which for girls. If one defied the rules, punishment was harsh; individualism was forbidden. But the shared traditions and communal interactions made the village a place of succor when trouble came. Poor farmers without their own baths usually used the ofuro of a richer villager. If a family lacked implements to till its own fields, it was common for neighbors to prepare the land for them—probably at night, so the family would not be embarrassed. Hardship bore less of a stigma in the village, because it was so widely shared.

The urban setting, by contrast, lacked human networks. Although some slums began to develop a sense of internal community near the end of Meiji, during the high-growth period under discussion here, most people felt disconnected from any larger whole. Single men dominated in the hinminkutsu of the 1890s, and it was not unusual for apartments to be inhabited by half a dozen people who had not known each other before. Because official regulations were a threat or a nuisance, urban migrants tended to flout legal requirements for registration or education, and the social isolation meant that mothers had no one to care for their children when they had to work. If urban hinmin fell sick, they had neither competent doctors nor public assistance to turn to. Indeed, the late Meiji government provided virtually no aid of any kind for the poor, except in times of some great disaster. One study found that between 1895 and 1910, an average of just 128 people a year received any official assistance in Tokyo.23 The sense of human isolation tore at the heart of journalist Yokoyama Gennosuke (1871–1915) when he saw a klatch of teenage girls outside a factory at New Year, talking about how they missed their families; he pronounced them “pathetic.”24 Poverty made life difficult no matter where one lived, but the absence of community in the city often turned difficulty into desolation.

Closely tied to the difference in human networks was a fifth contrast: the possibility of escape routes in the rural areas. While most slum-dwellers hoped for gradual improvement over the years, short-term escape was beyond imagination; even the idea of returning to the village was closed off except in the most extreme situations. In the countryside, however, geographical options were a real possibility for most families: sending “extra” children to factories or brothels, or pushing them into the great migration to the cities. The most widely discussed escape route in southern and western Japan was by sea, to the plantations and mines of South America and Hawai`i. Hawai`i’s sugar plantation owners, in particular, began aggressively seeking Japanese workers in the 1880s, and by the end of the Meiji era, more than 80,000 people had moved from Japanese farms to the mid-Pacific islands, where they soon would make up 40 percent of the population— and from where they would send millions of yen in remittances back to their home villages. As one émigré explained when poverty made life impossible on his Yamaguchi farm, “I had been born poor, and there was nothing I could do about that”; so he embraced the option of many peers and sailed to Hawai`i. City hinimin, unfortunately, had no similar choices, partially because of the transportation costs of going abroad but mostly because officials refused to allow the recruitment of urbanites for foreign farm work.25

A final difference lay in educational opportunity. The onrush of modernity made education a priority for the early Meiji leaders, and in 1872, Japan adopted the world’s first universal compulsory education system, requiring that boys and girls receive four years of school. Later, the requirement was increased to six years. The financing of a national system was difficult, but the results were impressive, and by the early 1900s, close to 90 percent of Japanese could read.26 Unfortunately, many of those who remained illiterate were urban hinmin. Although many farmers initially resisted a mandate that took their children out of the fields, they gradually grew used to it, and by the 1890s, most village children went to school. In the cities, by contrast, schools remained unavailable to vast numbers of hinmin children, no matter how much their parents valued education. Poverty dictated that children had to bring in income if the family were to survive. And that left no time for school. The few reformers who fought to change things were opposed by industrialists who wanted a cheap labor pool and by colluding officials who exempted the poor from compulsory education regulations, with the result that urban illiteracy remained high until the last Meiji years. Observed reporter Harada Tōfū: “The poor as a whole never have an education.”27 Another reporter commented in 1902 on the psychological toll this difficulty took on rickshaw pullers who “shed tears” because they had to keep “the children they loved” out of school “due to the difficulty of making a living.”28 Hinminkutsu parents were more aware than their rural relatives of how much modern children needed education—and that fact made poverty’s burden harder still.

Economic historian Nakagawa Kiyoshi argues that late Meiji villagers had “no sense of hinkon (poverty). You could be cold or hungry, but it was not conceptualized as poverty, only as a lack.” In the city, by contrast, hinmin were intensely aware of how poverty set them apart from other urbanites.29 Location, in other words, made economic deprivation feel different. In both village and city, impoverished families shared a special vulnerability to oppressive forces and a determination to make life better; they also shared a willingness to work harder than many of their more affluent peers. But the differences in the way they understood life were significant. The variety of jobs framed impoverishment for them differently. Slum-dwellers perspired (or shivered) at night in cramped alley-side shacks, while villagers confronted their troubles in relatively spacious homes. Nature provided lush environments in the village that softened (at least sometimes) the pain of having too little, while the tradition-bound, communal nature of rural life provided supports that largely were absent among urban strangers. And, somewhat surprisingly, schools opened new vistas for village children even as they heightened the sense of exclusion for urban families. All of this meant that while poverty was cruel and unforgiving everywhere, while it too often pushed villagers and city-dwellers alike over the precipice of destitution, it tended to feel even harsher in the late Meiji slums than it did in the countryside. That was a major reason urban journalists began, in the 1890s, to take up what was then a relatively new concept: “hinkon.” ■

- The 1902 government survey is from Inumaru Giichi, ed., Shokkō Jijō (Factory Workers’ Conditions), vol. 2 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1998; originally published 1903), 206–207. For comparative wages, see James L. Huffman, Down and Out in Late Meiji Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2018), 63, 71.

- See Nakagawa Kiyoshi, “Senzen ni Okeru Toshi Kasō no Tenkai, Jō” (“Evolution of the Urban Lower Classes in Prewar Japan,” Part 1), Mita Gakkai Zasshi (June 1978), 68–69; also Deborah J. Milly, Poverty, Equality, and Growth: The Politics of Economic Need in Postwar Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 1999), 212–213.

- David L. Howell, “Proto-Industrial Origins of Japanese Capitalism,” Journal of Asian Studies 51, no. 2 (1992): 269– 286.

- W. Dean Kinzley, “Japan’s Discovery of Poverty: Changing Views of Poverty and Social Welfare in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Asian History 22, no. 1 (1988): 1.

- Survey cited in Yokoyama Gennosuke, Nihon no Kasō Shakai (Japan’s Lower-class Society) (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1949, originally published 1899), 227–230. The quote is from Matsubara Iwagorō, Saiankoku no Tokyo (Darkest Tokyo) (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1988, originally published 1893), 36, 48.

- Nagatsuka Takashi, The Soil: A Portrait of Rural Life in Meiji Japan, trans. Ann Waswo. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 67.

- “Absolutely must”: Iwagoro Matsubara, Sketches of Humble Life in the Capital of Japan (Yokohama: The “Eastern World” Newspaper Publishing and Printing Office, 1897), 71. This is an abridged translation of Matsubara’s Saiankoku. “Lazy”: A statement of Iwakura Tomomi, quoted in Kinzley, “Poverty,” 8.

- 1903: Inumaru, Shokkō jijō, vol. 1, 11, 35, 174; 1904: Shūkan Heimin Shinbun, January 31, 1904, 2.

- Interview in Kōloa: An Oral History of a Kaua’i Community, vol. 3 (Manoa: Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai`i–Manoa, 1988), 1307.

- William Johnston, The Modern Epidemic: A History of Tuberculosis in Japan (Cambridge: Council of East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1995), 83–86, 225.

- “Deficient”: Eiji Yutani, “‘Nihon no Kaso Shakai’ of Gennosuke Yokoyama” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1985), 200–201; Junichi Saga, “Dog Eaters”: Takagi Fukusaburō, “Outcasts,” Memories of Silk and Straw: A Self-Portrait of Small-Town Japan, trans. Garry Evans, (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1987), 51–53.

- Niroku Shinpō, May 13, 1900, 3.

- Harada Tōfū, Hinminkutsu (Slums) (Tokyo: Daigakukan, 1902), 109.

- Shimazaki Tōson, Chikuma River Sketches, trans. William E. Naff, (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1991), 67.

- Niroku Shinpō, March 22, 1901, in Suzuki Kōichi, Nyūsu de ou Meiji Nihon Hakkutsu (Uncovering Meiji Japan through the News), vol. 7 (Tokyo: Kawada Shobō Shinsha, 1995), 32.

- Tokyo fu Tōkeisho (Tokyo City Statistics) (Tokyo fu, 1901), 384–390.

- Described in Taiyō (November 5, 1901), 5–6.

- See Nakagawa, 85.

- See Maeda Ai, “In the Recesses of the High City: On Sōseki’s Gate,” in Text and the City: Essays on Japanese Modernity (Winston–Salem, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 334–335.

- Shimazaki, Chikuma River, 11.

- The Manyōshū (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), 206; Tayama Katai, Country Teacher, trans. Kenneth Henshall, (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1984), 203: (Seizō); Shimazaki, Chikuma River, 56 (Tōson).

- See Haruko Wakita, Anne Bouchy, and Ueno Chizuko, eds., Gender and Japanese History, vol. 2 (Osaka: Osaka University Press, 1999), 368.

- See chart in Nakagawa Kiyoshi, Gendai no Seikatsu Mondai (Modern Life Issues) (Tokyo: Hōsō Daigaku Kyōiku Shinkōkai, 2011), 65.

- Yutani, “Gennosuke Yokoyama” 272–273.

- For material on immigration to Hawai`i, see James L. Huffman, Down and Out, 224–258. For “born poor”: A Social History of Kona, vol. 4 (Manoa: Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai`i– Manoa, 1981), 753.

- Yamamoto Taketoshi, “Meiji Sanjūnen Zenhan no Shinbun Dokusha sō” (“Structure of Newspaper Readership at the Turn of the Century”), Shinbun Gaku Hyōron (March 1967), 123.

- Harada, 103.

- Terada Yūkichi, “Tokyo Shimin to Jinrikisha” (“Tokyo Citizens and Rickshaw Pullers”), Taiyō, April 5, 1902, 32.

- Interview, March 27, 1914.