In the most recent iteration of the AP World History (APWH) Curriculum Framework (CF) released for 2016–2017, China’s history explicitly appears in the CF for every period that the course covers. The overarching historical thinking skill is chronological reasoning, and two subsets that are explored in this article are analysis of patterns of continuity and change over time, and periodization. The skill of analyzing change and continuity over time has been a core part of the APWH course since its inception in 2001–2002, but periodization is one of the new subsets of historical thinking skills that all AP history courses are currently implementing for the curriculum and the AP national examination held in May.

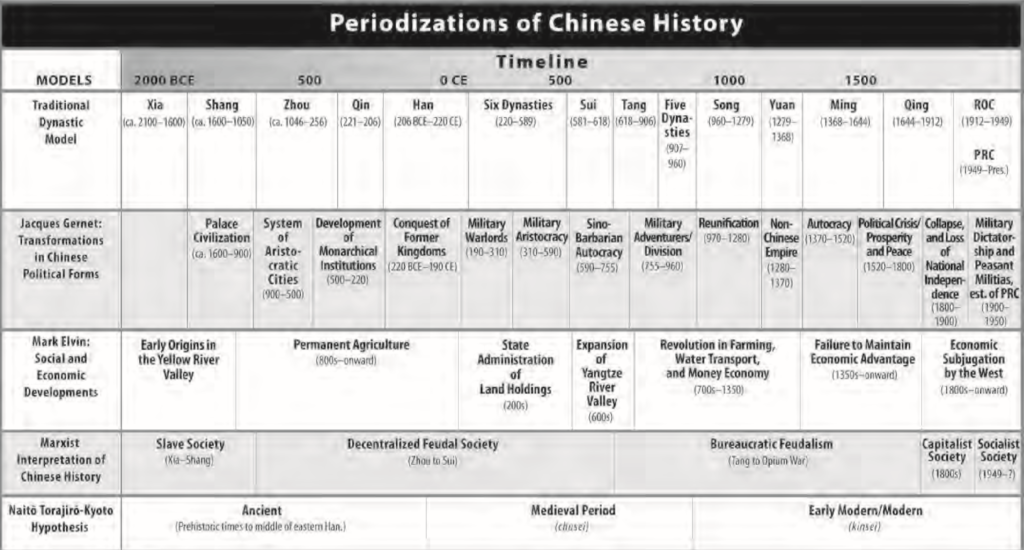

In this new emphasis on historical thinking skills in the AP World History course, the skill of periodization asks students to “analyze and evaluate competing models of periodization of world history.”1 Discussion of periodization is also important for APWH students to better understand the history of regional areas or countries. However, the AP World History framework presents Chinese history using the dynastic model, which is useful for the purposes of familiarizing students with the chronology of Chinese history, but perhaps not the best approach for the overall study of world history. Most importantly, when these different models are placed side by side (see chart), students can analyze for themselves the strengths and weaknesses of each periodization and evaluate their usefulness in understanding the imperial history of China.

. . . periodization is one of the new subsets of historical thinking skills that all AP history courses are currently implementing for the curriculum and the AP national examination held in May.

The dynastic model, which is the most commonly used and recognized for the study of Chinese history, is embedded into AP World History teaching practices nationwide. Many teachers use the “Chinese Dynasty Song,” sung to the children’s tune of Frere Jacques:

Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han

Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han

Sui, Tang, Song

Sui, Tang, Song

Yuan, Ming, Qing, Republic

Yuan, Ming, Qing, Republic

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong2

This little ditty has become a cornerstone activity for AP World History and world history educators. Search the “Chinese Dynasty song” online and there is a long list of videos that teachers have posted of their classes performing the song, in unison or as a round. It is so popular that even the widely subscribed online edX course, ChinaX out of Harvard University, has Professors William Kirby and Peter K. Bol providing a song offering “How to Memorize the China’s Major Dynasties” on a YouTube video.3 I enjoy using this catchy tune in the high school classroom as a fun classroom break or quick review. Students never forget the order of the Chinese dynasties, even years later. However, it is problematic if the teacher or professor merely ends students’ study of Chinese history with a simplistic understanding of Chinese dynastic order. This activity provides no basis for chronological reasoning, and does not help students in terms of analyzing and evaluating “competing models of periodization of world history,” nor does it help students in recognizing, analyzing, or evaluating “the dynamics of historical continuity or change over time of varying lengths.”4 The other shortcoming of simply studying the dynastic approach is that it only offers a model that can be seen as favoring those of the political elite as opposed to a more balanced coverage of world history in terms of economic, social, and/or cultural history. The changes in each dynasty were generally associated with a change in ruling family, but it does not necessarily follow that the economic structure, social structure, or culture also changed.

One of the critiques of this traditional dynastic approach came initially from esteemed Chinese historian John K. Fairbank, who wrote that “the concept of the dynastic cycle . . . has been a major block to the understanding of the fundamental dynamics of Chinese history.”5 Additionally, Professor Paul Halsall provided a similar critique on a website for Chinese cultural studies when he was teaching at Brooklyn College. According to Halsall, the system of periodization is problematic because “dynastic chronology seems to suggest that there were changes in Chinese life at times when change was not evident on a widespread basis,” but on the flip side, “suggests a degree of continuity that was not present either.”6 Halsall draws upon two other well-regarded works of Chinese history: Jacques Gernet’s A History of Chinese Civilization and Mark Elvin’s The Pattern of the Chinese Past. Halsall provides a quick summary of the two historians who offer and define a different Chinese historical periodization.

Of the first, Gernet looks at China’s political structures and identifies them in terms of political patterns, rather than dynastic ruling families. In this model, the political continuities and the major shifts are clearly recognized and defined, such as “palace civilization” or “system of aristocratic cities.” These labels, as seen in the attached chart, generally follow somewhat closely to the traditional dynastic model, but offer students an opportunity to recognize continuities in the political structure that the dynastic model does not.7 Again, this model has similar shortcomings to the dynastic model in that it only offers an understanding that is specific to China and does not help connect Chinese history to broader global events, except in the identification of the “non-Chinese empire” that corresponds with the Yuan Dynasty being in power. This classification does not provide much insight, even into the political structure that existed under foreign rule.

Elvin’s model looks at Chinese history through an economic perspective, which is more effective for the study of world history because it recognizes the broader scope of changes and continuities in China, which is more consistent with the study of bigger themes of world history, such as Theme 4: Creation, Expansion, and Interaction of Economic Systems.

Discussion Questions:

- What are the problems with the traditional dynastic approach?

- Suggests changes in Chinese life when change not evident (only political)

- Suggests degree of continuity that is not always there (other side of coin) Stresses history of political elite

- Overlooks economic and agricultural life (which affected a much higher percent of population throughout Chinese history)

- Does Gernet’s model have the same issues? What else does it offer?

- Does Elvin’s model have the same issues? What else does it offer?

- Does the Marxist model have the same issues? What else does it offer?

Synthesis Questions:

- Should each Chinese dynasty be seen as a “separate” empire? Or should Chinese dynasties be considered ONE continuous empire?

- Compare the traditional dynastic model with Mark Elvin, who asks the question, “Why did the Chinese Empire stay together when the Roman Empire, and every other empire of antiquity or the Middle Ages, ultimately collapse?”

- How do these different models help deepen our understanding of Chinese history?

- Can these different types of models be applied to other empires in world history?

In approaching Chinese history with more than the traditional dynastic model, it allows students to analyze Chinese imperial history as more of a continuum rather than separated political systems.

Although looking through an economic lens in itself is not sufficient for a deeper understanding of Chinese history, this model offers a more global perspective. The second periodization that Elvin offers is “permanent agriculture,” which spans the length of three dynasties. This model seems too broad at first glance, but can help students understand the continuity of the lives of the common peasants, which did not change over the span of those approximate 1,200 years. This broader perspective aligns with the continuities of many other early societies around the world at the same time, which makes this a helpful model to use for a more global approach to studying world history.

Along with the above three models, I have also added two additional periodization schemes for AP World History students to consider in their study of Chinese history. One is based on Marxist thought and the second is based on early twentieth-century historiography of Chinese history. There are dozens of Marxist models available, but I chose the official periodization of Chinese history of the People’s Republic of China.8 This model is a little difficult for students to understand, especially since we have not studied Marxism at this point in the curriculum. However, in looking at the chart, they can see that the Marxist periodization of history is vastly different than the other three models in its categorization of five periods of Chinese history, which correspond to Marxist historiography. Students can distinguish that the Marxist approach is primarily economic, thus more similar to Elvin’s model.

The final periodization model offers another interpretation and is from Japanese historian Naitō Torajirō (Konan), who is a sinologist and the founder of the Kyoto School of Historiography. Naitō also helped reshape the twentieth-century Western view of China. Although he wrote in the early twentieth century, his scholarship and redefinition of Chinese periodization offer a surprisingly simple but world historical perspective in contemplating Chinese chronology and history. In a short entry found in the Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Naitō is credited with:

His periodization of Chinese history into the equivalents of ancient, medieval, and modern. This scheme is already apparent in his Shinaron (On China) of 1914, which set the medieval/modern divide at ca. 800–1000 CE, the ‘Tang-Song’ transition, in contemporary parlance. It was more novel than one might imagine: before his time the notion of a ‘Golden Age’ in Chinese antiquity followed by long decline had been widespread in East Asia, and had been taken up with a vengeance by Westerners, who saw their own arrival in China as the stimulus that would arouse that country from complete torpor.9

Naitō’s model provides a competing model that becomes the basis of contrast for students to analyze against that of the traditional dynastic approach. Naitō, who uses the European classification of “ancient,” “medieval,” and “early modern,” redefines what has been largely Eurocentric definitions. With some prompting, usually only one or two students in each class understand the significance of Naitō’s model. By this time in the curriculum, students are used to being challenged to think in a more global context, thinking about different models of periodization of world history, and this step in putting the study of China into sharper focus brings it all together for them. Even if only one or two students can articulate the significance of Naitō’s model or the Marxist model in terms of understanding world history, it becomes a key point of the lesson, and one that extends beyond the simple study of Chinese dynastic history. Naitō’s model makes an argument that challenges the Western and Eurocentric approach of looking at history, but can also be so simplistic that it does not provide meaning to the students unless they already have a solid grasp of Chinese history.

In approaching Chinese history with more than the traditional dynastic model, it allows students to analyze Chinese imperial history as more of a continuum rather than separated political systems. Most students can understand how the five models presented are limited and problematic if they utilize the scheme of analyzing changes and/or continuities over time. Howard Spodek, author of The World’s History, raised the question in his textbook that during the early establishment of an imperial political structure, “China created political and cultural forms that would last for another 1,000 years, and perhaps even to the present.”10 This bold statement, mostly glossed over by students and teachers alike, presents a good opportunity for students to analyze the pattern of continuity within Chinese history. In the AP World History course, the concept of continuity is a challenging one for students to grasp. By providing different models, students are given an opportunity to think more deeply about what aspects of Chinese society have changed or continued beyond a basic political definition. Teachers can help students synthesize this exercise by asking whether each dynasty should be considered a separate empire. In my discussions with students, the arguments for considering each dynasty separately include the assertion that some dynasties approached their rule much differently than their predecessors. Arguments for considering imperial China as one continuous empire can be compelling if examining the Chinese political bureaucratic structure set into place by Qin Shi Huangdi, which was maintained and strengthened under the Han Dynasty, and was also adopted by foreign rulers such as the Mongols in the Yuan.

Looking at different models of periodization for one place or a limited time frame helps students understand history through a more complex lens.

So why is this level of analytical detail important for AP World History students to understand? It certainly ventures beyond the necessary level of historiography that is required of AP World History students, or even of undergraduates who are studying history. Looking at different models of periodization for one place or a limited time frame helps students understand history through a more complex lens. It pushes them to draw on their understanding of the global processes of the periods they are studying. China’s dynastic chronology is an ideal topic because it is already covered widely in AP World History classrooms, and students and teachers of world history are familiar with the traditional dynastic model. These various models provide another entry point for students to understand world history in a more global context, and for students to see that the issue of periodization is not just an academic discourse and debate amongst historians, but can have important implications on their overall understanding of history.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barrett, T. H. Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Vol. 2. Edited by Kelly Boyd. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999. https://books.google.com/books.

College Board. “AP Historical Thinking Skills.” Advances in AP. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://tinyurl.com/hmkhntd.

Columbia University. “Timeline of Chinese History and Dynasties.” Asia for Educators. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://tinyurl.com/z72cx9t.

Dirlik, Arlif. Revolution and History: The Origins of Marxist Historiography in China, 1919–1937. Berkeley, CA: University of CA Press, 1989. PDF eBook. http://tinyurl.com/ zlnbjb6.

Fairbank, John K., and Edwin O. Reischauer. East Asia: The Great Tradition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960.

Gernet, Jacques. A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972. Reprinted in 1989 by Cambridge University Press.

Halsall, Paul. “Chronology of Chinese History.” Chinese Culture, Core 9. Last modified June 2, 1999. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://tinyurl.com/88wt3w2.

“How to Memorize China’s Major Dynasties.” YouTube video, 1:00. From a presentation by the President and Fellows of Harvard Colleges. Posted by China X. November 3, 2013. http://tinyurl.com/je47cf6.

Perdue, Peter. “Eurasia in World History: Reflections on Time and Space.” World History Connected. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://tinyurl.com/zsvojxl

Spodek, Howard. The World’s History: Combined Volume. 4th ed. Boston: Prentice Hall, 2010.

NOTES

1. “AP Historical Thinking Skills,” Advances in AP, accessed March 30, 2016, http:// tinyurl.com/jyfqhvw.

2. “Timeline of Chinese History and Dynasties,” Asia for Educators, accessed March 30, 2016, http://tinyurl.com/z6zn6y5.

3. “How to Memorize China’s Major Dynasties,” YouTube video, 1:00, from a presentation by the President and Fellows of Harvard Colleges, posted by China X, November 3, 2013, http://tinyurl.com/je47cf6.

4. “AP Historical Thinking Skills,” Advances in AP, accessed March 30, 2016, http:// tinyurl.com/jyfqhvw.

5. Quoted in Peter Perdue, “Eurasia in World History: Reflections on Time and Space,” World History Connected, accessed March 30, 2016, http://tinyurl.com/.z8svqdh. Original citation: John K. Fairbank and Edwin O. Reischauer, East Asia: The Great Tradition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960), 115.

6. Paul Halsall, “Chronology of Chinese History,” Chinese Culture, Core 9, last modified June 2, 1999, http://tinyurl.com/88wt3w2.

7. Jacques Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization (1972; repr., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 22–25.

8. Arlif Dirlik, Revolution and History: The Origins of Marxist Historiography in China, 1919–1937 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989), PDF eBook, http:// tinyurl.com/jqcllll.

9. T. H. Barrett, Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, ed. Kelly Boyd (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999), 2:850–851, accessed March 30, 2016, https://books.google.com/books

10. Howard Spodek, The World’s History: Combined Volume, 4th ed. (Boston: Prentice Hall, 2010), 205.