Once and Future Warriors: The Samurai in Japanese History

By Karl Friday

Image source: Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185–1868, edited by Yoshiaki Shimizu. Published by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1988

The samurai exercise a powerful hold on popular imaginations, both in and out of Japan, rivaling cherry blossoms, geisha, and Sony as Japanese cultural icons. Emerging during the early part of the Heian period (794–1185), these warriors— known as bushi, tsuwamono, musha, mononofu, and other names at various times in their history—dominated the political and economic landscape by the early 1200s, and ruled outright from the late fourteenth to the late nineteenth century. Their story is, therefore, central to the history of premodern and early modern Japan, and has become the subject of dozens of popular and scholarly books. It also inspires a veritable Mt. Fuji of misperceptions and misinformation— a karate instructor in Japan once told me of a New Zealand man who came to live and train with him, and who was absolutely convinced that samurai were still living on some sort of reservation on the back side of a nearby mountain!

Until a generation ago, scholars pondering the samurai were all-too-readily seduced by perceptions of an essential similarity between conditions in medieval Japan and those of northwestern Europe. Samurai and daimy¬ (the regional military lords who emerged during Japan’s late medieval age) were equated with knights and barons; and theories on the origins and evolution of the samurai were heavily colored by conceptions of how the knights and their lords had come to be. Such comparisons and reasoning by analogy can be found in the descriptive essays of the first Jesuits in Japan, continued in the writings of nineteenth-century Western visitors to the islands, and were reified by succeeding generations of historians—to the point at which assertions like, “there are only two fully proven cases of feudalism, those of Western Europe and of Japan,” or “almost every feature of Japanese feudal development duplicated what had happened in Northern France,” could pass virtually unchallenged.1

Japan’s warrior order came into being to serve the imperial court and the noble houses that comprised it as hired swords and contract bows—just one of many byproducts of the broad trend toward the privatization of government functions and delegation of administrative responsibility that distinguished the Heian polity from its Nara era predecessor.

By the 1980s, however, historians were becoming increasingly uncomfortable with what one author eventually dubbed the “Western-analog” view of samurai history.2 Just as their colleagues in medieval European history were beginning to question the utility of hoary constructs like “feudalism,” scholars of medieval Japan were coming to regard the resemblances between knights and samurai or daimy¬ and barons as superficial, and more misleading than helpful to understanding what really happened in Japan. Medieval Japan and medieval Europe represented fundamentally different societies, knights and samurai were born under fundamentally different circumstances, and samurai political power evolved along a fundamentally different path into significantly different shapes and forms from those of European lordship.

The following essay, then, surveys the evolution of the samurai and warrior rule in premodern Japan, with special emphasis on the origins of both.

FROM WHENCE

The Nara (710 –794) and Heian (794 –1180) Periods

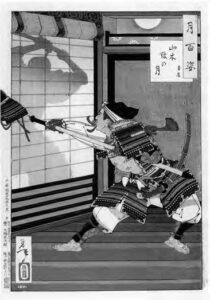

Yoritomo (1147–1199), leader of the Minamoto clan, sent Kat¯o Kagekado (pictured in this print) and others to attack Yamaki mansion, which was the base of operations for the

Taira clan. Image source: The Japan Print Gallery at: http://www.japaneseprints.net/viewitem.cfm?ID=2058

“The rise of the samurai” was less a matter of dramatic revolution than one of incremental evolution, occurring in fits and starts. Japan’s warrior order came into being to serve the imperial court and the no

ble houses that comprised it as hired swords and contract bows—just one of many byproducts of the broad trend toward the privatization of government functions and delegation of administrative responsibility that distinguished the Heian polity from its Nara era predecessor. Their roots came from a shift in imperial court military policy that began in the middle decades of the eighth century and picked up momentum in the ninth.

Around the turn of the eighth century, the newly restyled imperial house and its supporters had secured their position at the apex of Japan’s socio-political hierarchy through an elaborate battery of governing institutions modeled in large measure on those of T’ang China. These included provisions for domestic law enforcement and foreign defense. Contrary to the images that still dominate many popular histories, the new institutions were not simply adopted wholesale: the architects of the imperial state carefully adapted Chinese practices to meet Japanese needs and circumstances. At the same time, the planners all too often contended with conflicting priorities, and accordingly, incorporated some rather unhappy compromises into the final product. The original foibles of the system were, moreover, exacerbated by changing conditions: by the mid-eighth century the needs and priorities of the Japanese state differed considerably from those of the late seventh.

One of the difficulties the government faced was enforcing its conscription laws. Under the imperial state polity, military conscription was simply one of many kinds of labor tax, and induction rosters were compiled from the same population registers used to levy all other forms of tax. For this reason, peasant efforts to evade any of these taxes also placed them beyond the reach of the draft boards. Far more important than the reluctance of peasants to serve, however, were the fundamental limitations of the armies themselves.

The imperial state military system had been designed in the late seventh century, in the face of internal challenges to the sovereignty of the court and the regime, and the growing might of T’ang China, which had been engaged since the early 600s in one of the greatest military expansions in Chinese history. The architects of the new polity seized on large-scale, direct mobilization of the peasantry as a key part of the answer to both threats, creating a militia system that made all free male subjects between the ages of 20 and 59, other than rank-holding nobles and individuals who “suffered from long-term illness or were otherwise unfit for military duty,” liable for induction as soldiers.3 But while this military structure was more than adequate to the tasks for which it was designed, by the middle decades of the eighth century, the political climate—domestic and foreign—had changed enough to render the system anachronistic and superfluous in most of the country.

the Victoria and Albert Museum, edited by Richard Lane. Published by Kodansha International Ltd., 1991.

In the frontiers—particularly the north, where the state was pursuing an aggressive war of occupation—large infantry units still served a useful function. But the martial needs of the interior provinces—the vast majority of the country—quickly pared down to the capture of criminals and similar policing functions. Unwieldy infantry units based on the provincial militias were just not well-suited to this type of work. The sort of military forces most called for now were small, highly mobile squads that could be assembled and sent out to pursue raiding bandits with a minimum

of delay. In the meantime, diminishing military need for the regiments encouraged officers and provincial officials to misuse the conscripts who manned them—borrowing them, for example, for free labor on their personal homes and properties.

The court responded to these challenges with a series of adjustments, amendments, and general reforms. The most dramatic step in this direction came in 792, when the court abolished its infantry-centered regiments everywhere except the frontiers and other “strategic” provinces, but the broader pattern of edicts issued from the 730s onward shows that the government had concluded that it was more efficient to rely on privately-trained, privately-equipped elites than to continue to attempt to draft and train the general population. Accordingly, troops mustered from

the peasantry played smaller and smaller roles in state military planning, while the role of elites expanded steadily across the eighth century. The provincial regiments were first supplemented by new types of forces, then eliminated. In their place the court created a series of new military posts and titles that legitimized the use of personal martial resources on behalf of the state. In essence, the court moved from a conscripted, publicly-trained military force to one composed of professional mercenaries.

These measures served to make the acquisition of military skills an attractive path to personal advancement for provincial elites and low-ranking central aristocrats. In the meantime, expansive social and political changes taking shape in Japan during the ninth and tenth centuries spawned intensifying competition for wealth and influence among the premier noble houses of the court, which in turn led to a private market for military resources, arising in parallel to the one generated by government policies.

From the late ninth century onward, court society and the operations of government more and more became dominated by the heads of powerful familial interest groups and alliances. Intense political competition between these groups made control of military resources of one sort or another an invaluable tool for guarding the status, as well as the persons, of top courtiers and their heirs. As the system evolved, powerful nobles vied with one another to recruit men with warrior skills into the ranks of their household service, and to staff the military units operating in the capital with their own kinsmen or clients.

State and personal needs thus intersected to create broadening avenues to personal success for those with military talents. Skill at arms offered an ambitious young man growing opportunities to get his foot in the door for a career in government service and/or in the service of some powerful aristocrat. The greater such opportunities became, the more enthusiastically and the more seriously such young men committed themselves to the profession of arms. The result was the gradual emergence of an order of professional fighting men—in both the countryside and the capital—that came to be known as the samurai.

By the middle of the ninth century—perhaps as early as the late eighth—fighting men in the provinces had also begun to form themselves into privately-organized martial bands. By the third decade of the tenth century, private military networks of substantial scale had begun to appear, centered on major provincial warriors like Taira Masakado, who, we are told, could charge into battle “leading many thousands of warriors,” each themselves leading “followers as numerous as the clouds.”4 Although the government initially opposed such networks, it soon came to realize that they could be useful in filling a gap created in the state military system by the dismantling of the provincial militias in 792. For without the militias, the court had no formal mechanism through which to call up troops when it needed them. During the early tenth century, however, it began to co-opt private military organizations to provide just such a mechanism, now transferring much of the responsibility for mustering and organizing the forces necessary for carrying out military assignments to warrior leaders, who could in turn delegate much of that responsibility to their own subordinates.

THE ADVENT OF WARRIOR RULE

The Kamakura Period (1180–1333)

Unlike medieval Europe, where knights and military lordship arose more or less in tandem, Heian Japan remained firmly under civil authority; the socio-economic hierarchy still culminated in a civil, not a military, nobility; and the idea of a warrior order was still more nascent than real. Warrior leaders still looked to the center and to the civil ladder for success, and still saw the profession of arms largely as a means to an end—a foot in the door toward civil rank and office. During the Heian period, warriors thought of themselves as warriors in much the same way that modern corporate executives view themselves as shoemakers, automobile manufacturers, or magazine distributors: that is, just as business executives tend to identify more closely with their counterparts in other firms and other industries than with the workers, engineers, or secretaries in their factories, design workshops, and offices; so too did warriors at all levels in the socio-political hierarchy identify more strongly with their non-military social peers, than with warriors above or below them in the hierarchy. While the descendants—both genealogical and institutional—of the professional warriors of Heian times did indeed become the masters of Japan’s medieval and early modern epochs, until the very end of the twelfth century the samurai remained the servants, not the adversaries, of the court and the state. Then, in 1180, Minamoto Yoritomo, a dispossessed heir to a leading samurai house, adeptly parlayed his own pedigree, the localized ambitions of provincial warriors, and a series of upheavals within the imperial court into the creation of a new institution—called the shogunate, or bakufu, by historians—in the eastern village of Kamakura.

http://www.castlefinearts.com/index.htm

The events that led to the birth of Japan’s first warrior government began in 1159, when Yoritomo’s father, Yoshitomo, joined a clumsy attempt to seize control of the court. In the resulting Heiji Incident (named for the calendar era in which it occurred), Yoshitomo was defeated by his long-time rival Taira Kiyomori, who then gleefully executed Yoshitomo’s allies and relatives, and exiled his sons—including Yoritomo, who was thirteen at the time.

For the next two decades, Kiyomori’s prestige and influence at court grew steadily. In 1171 he arranged to marry his daughter, Tokuko, to the emperor. In 1179 he staged a coup d’etat, seizing virtual control of the court. Kiyomori reached the height of his power in 1180, when his grandson (by Tokuko) ascended the throne as Emperor Antoku. That same year, however, a frustrated claimant to the throne, Prince Mochihito, provided Yoritomo with an opportunity for revenge.

Yoritomo was, by any reckoning, an unlikely champion: in 1180 he had even less going for him than typical warrior leaders of his age. His father’s misadventure two decades before had cost him the career as a government official and warrior noble he would otherwise have enjoyed, and doomed him instead to an obscure life as a minor provincial warrior. He held no government posts, led no war band of his own, and controlled no lands. His one and only asset was a shaky claim to leadership among his surviving relatives. And so, being unable to work within the system, Yoritomo instead hit on an ingenious end run around it.

He used Mochihito’s call to arms to rescue the court from Kiyomori as a pretext to issue one of his own, declaring a martial law under himself across the eastern provinces, and declaring that, in return for an oath of allegiance to himself, henceforth he (Yoritomo) would assume the role of the court in guaranteeing whatever lands and administrative rights an enlisting vassal considered to be rightfully his own. In essence, Yoritomo was proclaiming the existence of an independent state in the East, a polity run by warriors for warriors.

But he took pains to portray himself as a righteous outlaw, a champion of true justice breaking the law in order to rescue the institutions it was meant to serve. This touched off a groundswell of support, as well as a countrywide series of feuds and civil wars loosely justified by Yoritomo’s crusade against Kiyomori and his heirs.

In the course of this so-called Gempei War (the name derives from the Sino-Japanese readings for the characters used to write “Minamoto” and “Taira”), however, Yoritomo revealed himself to be a surprisingly conservative revolutionary. Rather than maintain his independent warrior state in the East, Yoritomo instead negotiated a series of accords that gave permanent status to the Kamakura regime, trading formal court recognition of many of the powers he had seized, for re-incorporation of the East into the court-centered national polity.

One way to understand the first shogunate, its relationships to the imperial court and to samurai in the countryside, and its role in governing Japan—is to think of it as a kind of warriors’ union.

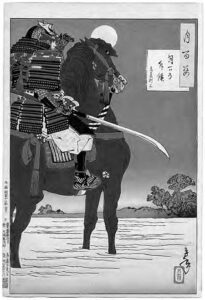

Depicts General Nitta Yoshisada (1301–1338) as he prayed to the sea gods for assistance before a battle. Image source: The Japan Print Gallery

http://www.japaneseprints.net/viewitem.cfm?ID=2058

The regime that this agreement established—the Kamakura shogunate—was a kind of government within a government, both part of and distinct from the court in Kyoto. It acted as the main military and police agency of the court, exercised broad governing powers in eastern Japan, and held special authority over the warriors, scattered countrywide, that it recognized as its formal vassals. After the J¬ky† War of 1221, an ill-fated attempt by a retired emperor, Go-Toba, to eliminate the shogunate, the balance of real power shifted steadily toward Kamakura, and away from Kyoto. By the end of that century, the shogunate had assumed control of most of the state’s judicial, military, and foreign affairs.

Following Yoritomo’s death in 1199, control of the regime fell into the hands of his in-laws, the H¬j¬ family. It was, in fact, the H¬j¬, not Yoritomo himself, who made the new regime a shogunate, that is, a government under a Seii taish¬gun (Great General for Subduing the Barbarians). This was a very old title, a temporary, wartime commission given to generals who led imperial armies in the East. Yoritomo held it briefly from 1192 to 1195; his son and successor, Yoriie, held it for just under a year, beginning in late 1202. In 1203, however, Yoritomo’s widow, Masako, her father, H¬j¬ Tokimasa, and her brother, Yoshitoki, deposed Yoriie and replaced him with his brother, Sanetomo. They legitimized this new power arrangement by having Sanetomo appointed Seii

taish¬gun. Thus Sanetomo, who is remembered as the third Kamakura shogun, was actually the first to hold that title from the beginning to the end of his reign (1203–1219). But he and the six shoguns who followed him in the office were figurehead rulers, many of them children at the time they took office, while the H¬j¬ ran things behind the scenes as hereditary directors of the shogun’s private chancellery.

One way to understand the first shogunate, its relationships to the imperial court and to samurai in the countryside, and its role in governing Japan—is to think of it as a kind of warriors’ union. Before the creation of the shogunate, warriors in the provinces were merely local government administrators or caretakers for estates that belonged to court nobles or temples. The court kept them politically weak by playing them against one another. By insulating an elite subgroup of the country’s provincial warriors from direct court control or employ, the shogunate ensured that samurai could no longer be managed by playing them against one another. Initially this merely served to vault Yoritomo (and later the shogunate) into prominence. But in the long run, it created a mechanism for unraveling the fabric of centralized authority.

The eastern warriors who answered Yoritomo’s call to arms in 1180 came to him because they were frustrated by the limitations of their traditional place in the landholding and governing systems. Yoritomo exploited those frustrations to build his original vassal band, and then, through his military and diplomatic efforts over the next five years, extended this organization across the rest of Japan. As his regime developed, Yoritomo kept himself indispensable to both his men and the court by making himself the exclusive intermediary between them, insisting that all calls to service, all rewards, and all disciplinary matters involving Kamakura vassals pass through him. This arrangement became permanent—hereditary—under the H¬j¬ after Yoritomo’s death.

The existence of the shogunate, therefore, rested on two competing obligations: On the one hand, it had a mandate from the court to maintain order in the provinces, to keep its own men under control, and to use them to defend the court. This is what made the regime legal, and formed the basis of its national authority. On the other, the shogunate’s ability to carry out this mandate depended on the continuing support of its followers, which in turn hinged on its support of their ambitions for greater freedom from court control.

These competing obligations led the shogunate to adopt a policy of minimal action whenever it was called upon to resolve a dispute between one of its vassals and some court noble or temple. It never acted unless asked (by one or both of the parties involved), kept no records of its own on the proceedings or the results of such lawsuits, and rarely imposed penalties more severe than ordering the defendant to cease and desist from whatever it was that he had been doing to cause the complaint.

By the late 1400s, while both the court and the shogunate remained nominally in authority, real power in Japan had devolved to a few score regional warlords called daimy ¯ o, whose authority rested first and foremost on their ability to hold lands by military force.

Kamakura vassals across the country quickly learned to take advantage of this situation, manipulating their special status to lay stronger and more personal claims to their lands—and the people on them. They did this in much the same way that a persistent dog will sometimes crawl under the blankets and take over most of its owner’s bed.

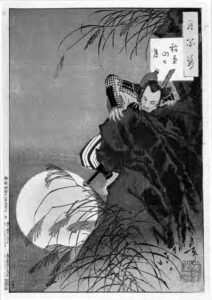

Yoshitoshi (1839–1892). Depiction of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–1598) as he climbs a cliff to gain access to the castle of his enemy. Image source: Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:YoshiClimber.jpg

The first step usually involved a warrior overstepping his authority in some small way—such as keeping more than his agreed upon share of the rents or taxes collected on the lands he administered. Because the warrior was a Kamakura vassal, the estate owner could not discipline the man himself; he could only complain to the shogunate. The shogunate, however, was less concerned with abstract matters of right and wrong than with keeping order, and minimizing bad feelings on either side. After hearing arguments and examining documents submitted, its rulings more often than not involved some kind of compromise between the claims of the two parties. This meant that the warrior got less than he had tried to seize, but also that the estate owner would, from then on, be forced to accept less than he had before the dispute began.

This sort of warrior behavior became more and more frequent, and more and more blatant, as the Kamakura period wore on. Settlements were followed by new violations and new compromise settlements, as the same warriors pushed the boundaries of their legal obligations over and over, generation after generation. The process worked like a ratchet: each new settlement represented a net gain for warriors and a net loss for the court.

Thus, through a gradual advance by fait accompli, real power over the countryside spun off steadily from the center to the hands of local figures, and a new warrior-dominated system of authority absorbed the older, courtier-dominated one. By the second quarter of the fourteenth century, this evolution had progressed to the point where the most successful of the shogunate’s provincial vassals had begun to question the value of continued submission to Kamakura at all. The regime fell in 1333, the result of events spawned by an imperial succession dispute.

WARRIOR RULE AND RULE BY WAR

The Muromachi (1138–1477) and Sengoku (1477–1600) Periods

Both the imperial house and the loyalties of the court had, since the 1260s, been divided between competing lineages descended from Emperor Go-Saga (r. 1242–46). The shogunate, which had taken an active hand in matters of imperial succession since the J¬ky† War, was able to keep this rift under control by arranging a compromise whereby the two lineages would alternate in succession. In 1318, however, Emperor Go-Daigo, of the Junior line, came to the throne, and immediately set about reorganizing the power structure around himself.

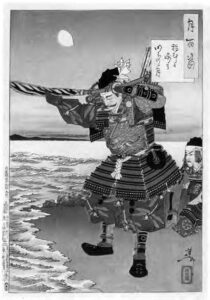

the series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892).

Depiction of commander Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–1598) as he sounds his conch shell horn to begin the battle of Shitzugatake. Image source: Man-Pai/Japanese Prints http://www.man-pai.com/Room3/emc015_g_e.htm

In 1331 Kamakura discovered that Go-Daigo had been plotting its elimination, and responded by forcing his abdication, and later his exile to the remote province of Oki. At this, Emperor K¬gon, of the Senior line, ascended the throne. In the second month of 1333, however, Go-Daigo escaped from Oki and took refuge with supporters, who had continued to be active in working against the shogunate. Kamakura responded by dispatching armies under Ashikaga Takauji and Niita Yoshisada to subdue the “loyalist” forces and recapture Go-Daigo. But in mid-course, both commanders turned on the shogunate, Takauji attacking and destroying its offices in Kyoto, and Yoshisada marching on Kamakura itself. In the sixth month of 1333, Go-Daigo returned to Kyoto, insisting that he had never formally abdicated, and proclaimed the start of a Kemmu (again named for the calendar era) Restoration of imperial rule. Within three years, however, he found himself once again driven from power, by the very men who put him there.

In 1335 Takauji changed sides yet again, and by the middle of the following year, had destroyed Go-Daigo’s coalition, forced the once and-future monarch to abdicate for a second time, and established a new shogunate, headquartered in the Muromachi district of Kyoto. Go-Daigo fled to the mountains of Yoshino, south of Kyoto, where he and his remaining supporters set up a rival court, insisting that the Takaujisponsored succession of Emperor K¬my¬ in Kyoto, had been illegitimate, and therefore illegal.

Warfare between the two courts broke out immediately, and rapidly spread across the country. Leading warriors shifted sides again and again, in response to advantages and opportunities of the moment, playing each court off the other in much the same way that the court had once kept warriors weak by pitting them against one another. As this happened, it took a predictably heavy toll on imperial authority. By the time the third Ashikaga shogun, Yoshimitsu, tricked the southern pretender, Go-Kameyama, and his followers into returning to Kyoto—subsequently reneging on his promise to reinstitute the old system of alternating succession—whatever remained of centralized power in Japan was in the hands of the shogunate.

Fifteen Ashikaga shoguns reigned between 1336 and 1573, when the last, Yoshiaki, was deposed; but only the first six could lay claim to have actually ruled the country. By the late 1400s, while both the court and the shogunate remained nominally in authority, real power in Japan had devolved to a few score regional warlords called daimy¬, whose authority rested first and foremost on their ability to hold lands by military force. There followed a century and a half of nearly continuous warfare as daimy¬ contested with one another, and with those below them, to maintain and expand their domains. The spirit of this Sengoku (literally, “country at war”) age is captured in two expressions current at the time: gekokuj¬ (the low overthrow the high) and jakuniku ky¬shoku (the weak become meat; the strong eat).

WITHER THE WARRIOR?

The Tokugawa Period (1600–1868) and Beyond

But the instability of gekokuj¬ could not continue indefinitely. Daimy¬ quickly discovered that the corollary cliché to “might makes right” is that “he who lives by the sword, dies by the sword,” and that many were spending as much time and energy defending themselves from their own ambitious vassals as from other daimy¬. During the late sixteenth century, the most able among them began searching for ways to reduce vassal independence. This in turn made possible the creation of ever-larger domains and hegemonic alliances extending across entire regions. At length, the successive efforts of three men—Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu—eliminated many of the smaller daimy¬ and unified the rest into a nationwide coalition. In 1603 Ieyasu assumed the title of sh¬gun and established Japan’s third military regime. The new polity, a kind of centralized feudalism, left most of the country divided into great domains ruled by hereditary daimy¬, who were in turn closely watched and regulated by the shogunate.

The advent of this new polity and the ensuing Pax Tokugawa marked the transition from medieval to early modern Japan, which brought with it profound changes for the samurai. In the medieval age, warriors had constituted a flexible and permeable order defined primarily by their activities as fighting men. At the top of this order stood the daimy¬, some of whom were inheritors to family warrior legacies dating back centuries, while others had clawed their way to this status from far humbler beginnings. Below these were multiple layers of lesser lords, enfeofed vassals, and yeoman farmers whose numbers and service as samurai waxed and waned with the fortunes of war and the resources and military needs of the great barons. But the early modern regime froze the social order, drawing for the first time a clear line between peasants, who were registered with and bound to their fields, and samurai, who were removed from their lands and gathered into garrisons in the castle towns of the shogun and the daimy¬. The samurai thus became a legally-defined, legally-privileged, hereditary class, consisting of a very few enfeofed lords and a much larger body of stipended retainers, whose numbers were now fixed by law. And, without wars to fight, the military skills and culture of this class inevitably atrophied. The samurai rapidly evolved from sword-wielding warriors to sword-bearing bureaucrats descended from warriors.

http://www.trocadero.com/MONTES/items/418305/

en1store.html

The Tokugawa regime kept the peace in Japan for the better part of three centuries, before at last succumbing to a combination of foreign pressure, evolution of the nation’s social and economic structure, and decay of the government itself. In 1868 combined armies from four domains forced the resignation of the last shogun and declared a return to direct governance under the emperor. This event, known as the Meiji Restoration (again named after the calendar era), marked the beginning of the end for the samurai as a class. Over the next decade they were stripped first of their monopoly over military service, and then, one-by-one, of the rest of their privileges and badges of status: their special hairstyle, their way of dress, their exclusive right to surnames, their hereditary stipends, and the right to wear swords in public.

By the 1890s, Japan was a modernized, industrialized nation ruled by a constitutional government and defended by a westernized conscript army and navy. The samurai had become what they remain today: figures of history, folklore, entertainment, and ideological symbolism.

Suggested Readings

Thomas Conlan, In Little Need of Divine Intervention: Takezaki Suenaga’s Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell East Asia Series, 2001).

Karl Friday, Samurai, Warfare and the State in Early Medieval Japan (New York and London: Routledge, 2004).

Eiko Ikegami, The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Marius Jansen, ed., Warrior Rule in Japan (New York & London: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Jeffrey P. Mass and William Hauser, eds., The Bakufu in Japanese History (Stanford, CA: Stanford, University Press, 1985).

Jeffrey P. Mass, ed., The Origins of Japan’s Medieval World: Courtiers, Clerics, Warriors, and Peasants in the Fourteenth Century (Stanford, CA: Stanford, University Press, 1997).

Helen Craig McCullough, tr., The Taiheiki: a Chronicle of Medieval Japan (Rutland, VT: Charles Tuttle, 1959).

Helen Craig McCullough, tr., The Tale of the Heike (Stanford, CA: Stanford, University Press, 1988).

H. Paul Varley, Warriors of Japan as Portrayed in the War Tales (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1994).

Notes

1. Rushton Coulborn, ed., Feudalism in History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1956), 185; Archibald Lewis, Knights and Samurai: Feudalism in Northern France and Japan (London: Temple Smith, 1979), 55. Emphasis on the “striking” resemblance of medieval Japan to medieval Europe persists in survey texts. Edwin Reischauer’s assertion that “Japan affords the only close and fully developed parallel to Western feudalism” (Japan: The Story of a Nation, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990, 46) is a case in point.

2. Wm. Wayne Farris, Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500–1300 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

3. Ry¬ no gige, in Shintei z¬ho kokushi taikei (Tokyo: Yoshikawa k¬bunkan, 1985), 192.

4. Sh¬monki, in Hayashi Rokur¬, ed., Sh¬monki (Tokyo: Imaizumi seibunsha, 1975), 101.