Editor’s Note: An article about music would be incomplete without enabling the reader to listen to the music the author considers. Web links to examples of the music discussed here are located at the end of this article. The same links are on our website for easy access.

The Meaning of “Music” in Afghanistan

The meaning of music in the West is broadly defined as humanly organized sound and includes both religious and secular music, both vocal and instrumental music, and music performed by both professional and amateur musicians. However, the meaning of music in Afghanistan is quite a bit more restrictive than our general understanding of the concept of music. It is secular, never religious. It is more instrumental than vocal, and it is performed mainly by professional musicians and sometimes by amateur musicians.

There is a general notion that music is religiously disapproved of in Islam, yet there is not one word of censure in the Qur’an about music. Instead, the definition of music and its standing is dependent upon an understanding of its perceived distance from religiously sanctioned or praiseworthy activities. For example, Qur’anic recitations or calls to prayers—no matter how musical they sound—are never considered music. The same can be said for lullabies when mothers sing to their children. Yet when they are accompanied by musical instruments and sung by professional musicians to a public audience, they are considered music. These examples show that factors other than musical sound are important considerations in the Afghan definition of music.

The mainstay of Islam is the Qur’an, the revelations of God as passed on to the Prophet Mohammad. The “voice” and the “pen” that convey the sounds and words of Qur’anic recitation are regarded with great respect and value in the Muslim world. For the faithful, the sound or voice of Qur’anic chant is the most immediate means of contact with the Word of God. The oral nature of the Qur’an’s revelation and transmission elevates the place of the human voice in Islamic societies. In this sense, singing is more closely al- lied to literature than to music. For example, the Persian word khandan means “to read” as well as “to sing.” The term qawwali, a musical expression of Sufi poetry, comes from the Arabic qaul, meaning “speaking” or “saying.”

Beyond the presence or absence of the voice in musical performance, the status and background of the performer is important in determining whether the performance is music or not. The main difference between a professional and an amateur musician is not one of professionalism but of birthright and the musical education that is assumed when one is born into a family of hereditary musicians. The amateur musician learns on his own or finds an ustad (master) professional musician willing to teach or share with him the deep knowledge of his art/profession. At opposite extremes of this spectrum of musicians are the non-musician shepherd who plays his homemade nai (end-blown reed flute) to entertain himself and his flock and a professional musician who plays his finely crafted rabab (a short- necked, plucked lute with a deep, skin-covered body) in a public concert or televised program. Also included in this wide spectrum of performances are various regional folk songs and instruments of Afghanistan, as well as the urban classical/popular genres of Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, and other urban centers of the country.

Regional Folk Music of Afghanistan

In order to appreciate the music of Afghanistan, one should be aware of Afghanistan’s long history and place in the world known as the “Cross- roads of Asia,” an important point along the Silk Roads, the great trade routes between Asia and Europe traversed by countless religious pilgrims and traders (including Marco Polo in the fourteenth century). Today, al- most all of Afghanistan’s ethnic groups have historical, cultural, and linguistic ties to peoples living outside its borders. Their current neighbors of Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, China, and Pakistan not only share with them their musical styles, genres, and instruments, but also have an influence on the regional styles of Afghanistan.

The music of southern Afghanistan is dominated by the music culture of the Pashtuns, who have a rich history of national pride and independence expressed in poetry composed by prominent Pashtun poets and warriors. Many of their songs are patriotic in nature, urging bravery and resistance against foreign domination. A major form of Pashtun folksongs is the landay, consisting of improvised couplets with a nine-syllable line and a thirteen-syllable line. The musical instrument most closely associated with the Pashtuns is the rabab, which is recognized and celebrated in Pashtun folk literature as a noble folk instrument. The rabab is featured in the story of Adam Khan and Durkhane, a Romeo and Juliet-like romance, in which the sound of the rabab—played by the hero, Adam Khan—first attracts the attention of the heroine, Durkhane.1

The rabab is carved out of a single piece of mulberry wood with a thin piece of wood as a lid for the neck and upper body and a skin membrane covering its lower hollow body. It has three main playing strings made of gut or nylon and metal drone and sympathetic strings numbering from twelve to fifteen. The metal strings are tuned to the melodic mode being played but are usually not struck or played; instead, they are allowed to vibrate sympathetically with the pitches played on the main strings. The sympathetic strings add rich harmonics to the deep, resonant tones for which the rabab is best-known. The instrument is often elaborately decorated with mother-of-pearl and bone inlays and regarded as objet d’art. It is a versatile instrument that not only provides accompaniment to songs or provides the melodic lead in ensembles, but in the hands of a master musician, it is a virtuosic solo instrument of Afghan classical music. In fact, it is reputed to be the predecessor of the Indian sarod. Today, the rabab is indisputably the premier and best-known of all the musical instruments in Afghanistan.

The folk music of western Afghanistan is closely related to folk traditions of Iran, particularly the greater historical region of Khorasan, including areas of northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Afghanistan. It is a Persian-speaking area with Herat as its main commercial and cultural center. An important improvised folk song genre of the region is known as chahar baiti (four lines or quatrain). Although chahar baiti literally refers to “four lines,” it actually refers to couplets comprised of four half-lines with the rhyme scheme AABA. These short poems are usually composed on the subject of love and sung one after another, often inspiring new compositions. The following is an example of a popular chahar baiti written as four half-lines of verse with the rhyme scheme of AABA.

Maqorban-e sar-e darwaza mesham (A)

Sadayat meshnawom estada mesham (A)

Sadayat meshnawom az dur o nazdiq (B)

Ma misli ghumcha-ye gul taza mesham (A)

I sacrifice myself at your doorstop

[When] I hear your voice, I stand

[When] I hear your voice from far or near

I become as fresh as a flower bud

The Taliban confiscated and destroyed music cassettes, videotapes, and musical instruments; harassed and arrested musicians, listeners, and hosts of events where music was performed; [and] allowed no public performances, neither live nor recorded . . .

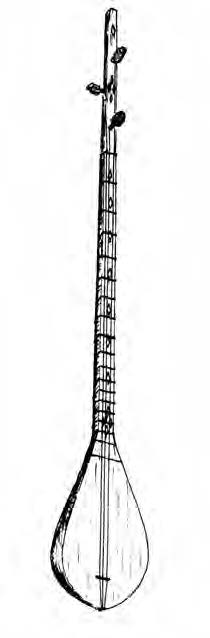

dutar is a long-necked, plucked lute with three metal strings and is an adaptation of the original twostring dutar with gut strings. it is played with a metal plectrum,

nakhonak. Length: 39 inches.

illustration by S. T. Sakata.

The popular folk instrument of the area is known as dutar, literally “two strings.” It is a small, long-necked, fretted, plucked lute that is light, portable, and commonly found in teahouses for guests to play. Although its name indicates that the original instrument had two strings, it is more common to find a dutar with three or five metal strings.

A larger, more professional version of the Herat dutar has three main playing strings with additional sympathetic strings that are tuned to different melodic modes, enabling it to play a solo, classical repertoire. Al- though the population of northern Afghanistan is a mix of Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Pashtuns, and other ethnic groups, the Tajiks and Uzbeks rep- resent the predominant urban population of the region. They share a musical style featuring songs in Tajiki or Uzbeki, or sometimes in a mixture of these two languages, identified as shir o shekar, “milk and sugar,” a reference to the blending of the two common languages of northern Afghanistan. Like the folk songs of Herat, they are improvised quatrains based on the poetic form of chahar baiti.

The most common regional instrument is the dambura, a two-stringed, fretless, long-necked lute with frontal pegs. Like the smaller dutar of Herat, the dambura has two gut or nylon strings and is used to accompany songs. It is commonly found in teahouses for customers to play. Unlike the Herat dutar, a larger, more complex version of the dambura has not developed into a solo, classical instrument.

Urban Classical and Popular Music

Folk music, by definition, refers to regional, nonprofessional “music” (what many Afghans consider nonmusic) for self-amusement or private performances. On the other hand, classical art or popular music implies a system of training, patronage, and public performances rarely found outside the context of an urban environment. Although there are individuals in Afghanistan who are involved in learning or performing Iranian and Tajik/Uzbek classical music, i.e., Persian radif or Central Asian shash maqam, on the whole, the classical music tradition of Kabul, based on the Hindustani raga tradition of North India, has been adopted as the classical music tradition of Afghanistan.

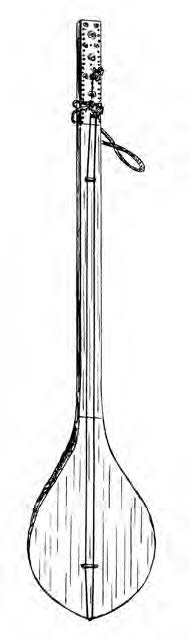

illustration by S. T. Sakata.

The rise of Afghan popular music in the 1960s can be attributed to a group of dynamic, young, Westernized high school students in Kabul who were exposed to Western music (some had conservatory training) and played Western instruments such as accordion, guitar, piano, and drums. One of these talented musicians was Ahmad Zahir, the son of Dr. Abdul Zahir, a respected physician and political leader who was the prime minister of Afghanistan in 1971–72. Ahmad Zahir was a handsome, charismatic singer and composer who sang traditional songs with Western sounds and rhythms, composed new songs that served as political commentary, and built a huge fan base by making a great number of recordings and performing at large public concerts in Kabul. He became a huge star that equaled the fame of some popular music idols in the West. In 1979, at the height of his career, he died in a car accident that most Afghans believe was an assassination made to look like an accident. The dramatic circumstances of his death, coupled with his tremendous popularity, made him legendary not only in Afghanistan, but in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and Iran, as well as in the Afghan diasporic communities in Europe and North America. Even more than thirty years after his death, he is remembered and revered, and many young singers aspire to be like him.

The “Golden Age” of Music

There are moments in history when a confluence of situations, events, or personalities provides optimal conditions for the development of certain ideas or trends. The era that is thought of as the “Golden Age” of music, from the 1950s through the 1970s, refers to a time when the country was stable and peaceful under the rule of Mohammad Zahir Shah (1933–1973). The king adopted modern and democratic reforms, such as the lifting of the compulsory veiling of women in 1959 and the adoption of a new constitution in 1964, designating Afghanistan a constitutional monarchy. The music of Kabul, and that of the nation, developed out of the musical tastes of the urban elite and its politically influential population during this time. They were listeners and supporters of the music of two major institutions in Kabul, the royal court and the radio station.

Under the rule of Amir Sher Ali Khan (1863–66 and 1868–79), north Indian musicians were invited to become court musicians in Kabul. They were given land in the section of Kabul known as kharabat (entertainment quarters) where they settled. Since that time, the Hindustani classical tradition of north India became established as the elite, art tradition of Afghanistan. Court patronage for musicians continued through the reign of King Zahir Shah, who regularly invited Afghan and Indian artists and musicians to his court for private performances and music lessons for individual members of the royal family.

A radio transmitter was first introduced to Afghanistan during the reign of Amanullah Khan (1919–1929) as part of his efforts to modernize the country, but with limited transmission coverage, broadcasting did not last beyond a few years. In 1941, a government radio station was established in Kabul, known as Radio Kabul and administered by the Ministry of Information and Culture. In 1964, Radio Kabul changed its name to Radio Afghanistan. With the addition of television coverage in 1974 (under President Daoud), both the government radio and television stations were identified as Radio Television Afghanistan, or RTA.

In a population of diverse ethnic and linguistic groups, largely illiterate and lacking access to other forms of media, Radio Kabul Afghanistan be- came the unifying voice of the nation, providing programming in the two main languages of Afghanistan, Dari (Persian) and Pashto. The station employed master musicians who, like other government bureaucrats, enjoyed official sanction, prestige, and support. They recruited female singers, mainly from the elite classes, in order to raise the status of women in the entertainment world. Radio musicians, with the help of foreign advisors, developed a musical style that combined stylistic elements and melodies from classical court music and regional folk traditions. They formed a national orchestra combining classical and regional folk instruments with some Western instruments. Its sound was identified as the radio style or the national style, the one with which all Afghans, both inside and outside the country, identified as their own. Throughout the unimaginable pain and suffering the Afghans endured in the past thirty years, this music helped them sustain their identity and culture.

The “Dark Age” of Music

If Afghanistan’s “Golden Age” of music blossomed under the rule of Mohammad Zahir Shah, Afghanistan’s “Dark Age” of music began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, when many Afghans emigrated out of Afghanistan to Pakistan, India, Iran, Europe, and North America. The emigration pattern of Afghan musicians was based on the economic status of the musician. Professional musicians, mainly instrumentalists, crossed the border into Pakistan, where they performed with and for the mainly Pashtun population in Pakistan. More affluent amateur musicians found their way to Europe and the US. The musicians who came to the West were mainly amateur singers from elite Kabul families. The only readily available instruments to accompany their songs were the Indian tabla, harmonium, and electronic keyboard.

After years of civil war, the “Dark Age” of music culminated under the rule of the Taliban, an Islamist militant group who ruled large parts of Afghanistan as the “Islamic emirate of Afghanistan” from 1996 to 2001. They are remembered for their harsh interpretations of Islamic law, cruel repression of women, massive human rights abuses against the general population, and ruthless banning of music that they deemed un-Islamic and immoral, including all instrumental music or songs with instrumental accompaniment. The Taliban confiscated and destroyed music cassettes, video- tapes, and musical instruments; harassed and arrested musicians, listeners, and hosts of events where music was performed; allowed no public performances, neither live nor recorded; and even raided private events, such as weddings, where music was a traditional part of the celebrations.

The Taliban’s own tradition of songs was chanted without instrumental accompaniment and, therefore, not considered music. Musically speaking, however, these chants were stylistically related to regional Pashtun folk song styles, and the song texts promoted Taliban ideals in the tradition of patriotic war ballads of the Pashtuns. Although the Taliban chants were unaccompanied, they often used technical devices like exaggerated reverb to “accompany” their songs. It is ironic that when the Taliban took over Radio Afghanistan, the institution that played a prominent role in developing the music identified with the “Golden Age” of music, they insisted that the station, which they had renamed Radio Shariat, record their chants for broadcast. Instead of destroying the old music tapes, they directed the radio staff to erase and reuse them to record their chants.

The single, most outrageous act for which the Taliban is remembered was the destruction of two sixth-century giant, standing Buddhas in the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan. It was a deliberate act of defiance in the face of the huge international outcry when the Taliban announced its intentions to dynamite the statues. Like music, they saw these statues as un-Islamic symbols of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage about which they had no knowledge and no appreciation. They intentionally wanted the Afghans to cut their ties to the past and to create a “pure” Islamic state with little or no foreign influences (forgetting that their strongest allies were foreign). Ironically, their harsh and repressive policies against the local population attracted the attention of international communities that administered assistance through NGOs in the country, even during the Taliban rule, and continued after the US and UN forces entered Afghanistan to oust the Taliban in 2001.

New Beginnings: The “ International Age” of Music

In 2004, the new government of Afghanistan commissioned a national anthem to symbolize the revival of their nation. The new constitution explicitly states that the national anthem must be in the Pashto language, must contain the phrase “Allahu Akbar” (meaning “Allah is greater”), and must mention names of the ethnic groups in Afghanistan. The Karzai government had to look outside Afghanistan to commission artists to compose the national anthem because many of the best artists had emigrated during the years of war and devastation. The words to the anthem were written by Abdul Bari Jahani, an Afghan living in the US, and the music was composed by Babrak Wasa, an Afghan émigré living in Germany. The final version, adopted in 2006, was performed with the accompaniment of a European orchestra and recorded in Germany.

Since 2001, foreign aid in the fields of economic and cultural development has proliferated. Efforts are being made to support education throughout Afghanistan, with special attention paid to the education of girls everywhere and the training of professional women in urban centers. More recently, institutions of music education have received some attention and support from the international community. Traditionally, music education was provided in the context of private lessons in the home or in institutions where professional musicians worked. In late 2003, the Music Initiative of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture set up a music program in Kabul, based on the traditional ustad-shagird (master-student) training system used by professional musicians. A similar program was set up in Herat in 2006.

The National Anthem of Afghanistan

This land is Afghanistan — It is the pride of every Afghan

The land of peace, the land of the sword — Its sons are all brave

This is the country of every tribe — Land of Baluch and Uzbeks

Pashtoons and Hazaras — Turkman and Tajiks with them,

Arabs and Gojars, Pamirian, Nooristanis

Barahawi, and Qizilbash — Also Aimaq, and Pashaye

This Land will shine for ever — Like the sun in the blue sky

In the chest of Asia — It will remain as the heart forever

We will follow the one God — We all say, Allah is great, we all say,

Allah is great

Although there were opportunities for Western music training in Kabul by Turkish military advisors in the 1950s, formal music education classes sponsored by the Ministry of Education were first offered in 1973 and later at Kabul University, while some promising students were sent to European music conservatories for training. One of these conservatory-trained students was Ahmad Sarmast, the son of the late Afghan composer, conductor, and musician Salim Sarmast. Sarmast completed his studies at Moscow State Conservatorium and went on to receive his PhD in 2005 from Monash University in Australia. In 2006, he returned to Afghanistan to work with the Ministry of Education and international donors to establish the Afghanistan, National Institute of Music, ANIM. The school officially opened in 2010 offering a general academic curriculum and specialized music training for students from grades four to fourteen, allowing students to obtain a high school certificate and a diploma in music. Music training in both Afghan and Western music are taught by Afghan and international faculty.

Afghan communities abroad struggled to adapt to their new homes yet managed to maintain their identity as Afghans and keep their cultural ties to Afghanistan. An important link to their past was the appreciation of the music from the “Golden Age” of music, the music that reminded them of their lives in better times. Popular and traditional songs from the past, as well as new compositions in the same style, accompanied by instruments such as tabla, harmonium, and electronic keyboard, are performed at wed- dings and community celebrations and recorded in music studios for commercial sales. This new style of Afghan popular music has found its way back into Afghanistan, inspiring young Afghan popular music groups to adopt this new style while using Western instruments such as guitar and electronic keyboard.

Since 2002, Afghans have had access to international music through satellite television, radio, and the Internet. Afghan émigré musicians periodically return to Afghanistan where they perform, collaborate, or teach with their friends, family, and colleagues. Opportunities to exchange new musical ideas, as well as preserve traditional ones, give Afghan musicians the means to innovate new styles that reflect their contemporary world. These young, energetic, and open-minded Afghan musicians have not for- gotten Afghanistan’s historical position at the “Crossroads of Asia,” where opportunities to exchange new information and ideas were not only common but vital in keeping their musical traditions fresh and relevant to their lives. They understood the dire consequences of living in a country that was isolated from the modern world and took every opportunity to reach out to the international community, giving rise to Afghanistan’s new “International Age of Music.”

Afghan Music and More on YouTube and Vimeo

See Houmayoun Sakhi playing Afghan classical music on the rabab with tabla accompaniment, http://bit.ly/MryWmF.

See Abdul Karim Herawi playing the large Herat dutar with tabla accompaniment, http://bit.ly/Kzhde8.

See Safdar Tawakoli playing the dambura, http://bit.ly/NPKzpG. See Ahmad Wali’s first music video, http://bit.ly/aiOKiO.

To hear the recorded version of the Afghanistan national anthem visit http://bit.ly/MxxA66.

For a glimpse of the students, faculty, and classes at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, go to http://bit.ly/MxxF9s.

For an example of an international context for Afghan music, see Homayoun Sakhi and friends, http://bit.ly/wvCG0o.

Listen to the Afghanistan National Anthem, http://tiny.cc/nltvgw.

In June 2012, the documentary film Dr. Sarmast’s Music premiered at the Sydney Film Festival. To see excerpts from the film, visit the festival website at http://tiny.cc/jfuvgw. For the theatrical trailer, see http://vimeo.com/25853257.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baily, John. Music of Afghanistan: Professional Musicians in the City of Herat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

______. Songs from Kabul: The Spiritual Music of Ustad Amir Mohammad. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011.

Beeman, William O. Iranian Performance Traditions. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2011.

Sakata, Hiromi Lorraine. Music in the Mind: Concepts of Music and Musicians in Afghanistan. Originally published by Kent State University Press, 1983. Printed with new foreword, preface, and CD. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002.

______. “The Politics of Music in Afghanistan.” Ethnomusicological Encounters with Music and Musicians: Essays in Honor of Robert Garfias. Edited by Timothy Rice. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011.

Sarmast, Ahmad Naser. Ustad Mohammad Sarmast: A 20th-Century Afghan Composer: And the First Symphonic Score of Afghanistan. Center of South Asian Studies, Working.

______. “The Naghma-ye Chartuk of Afghanistan: A New Perspective on the Origin of a Solo Instrumental Genre.” Asian Music 38, no. 2 (2007): 97–114.

Slobin, Mark. Music in the Culture of Northern Afghanistan. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1976.

Tala’i, Dariush. Traditional Persian Art Music: The Radif of Mirza Abdollah. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2000.

NOTES

- The timeframe of Adam Khan and Durkhane is mentioned in L. Nasir and Mum- taz Heston, The Bazaar of the Storytellers (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan and Lok Virsa, 1989).