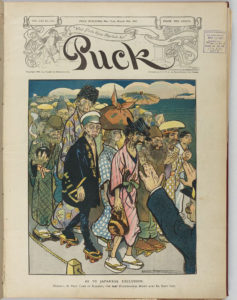

While Chinese exclusion remained an important political issue in the late nineteenth century, efforts to exclude Japanese immigrants gained momentum in the early twentieth century and culminated in the Japanese Exclusion provision of the 1924 Immigration Act. Anti-Japanese agitation, sometimes rising to the level of hysteria, occurred despite the fact that there was no great influx of immigrants from Japan. According to the annual report of the commissioner general of immigration, the continental US received just over 5,000 Japanese immigrants in 1900, with the number rising to just over 11,000 in 1905, hardly a massive increase. (note 1) As in the Chinese Exclusion movement, Japanese Exclusion was often justified publicly in racist terms. What made the Japanese immigration issue unique was its juxtaposition with the rise of Japan as a world power and the expansion of her empire. Paradoxically, Japanese immigrants were characterized by exclusionists as dangerous because of both their lower standard of living and their innate ability to succeed in their new land. In testifying on the 1924 Immigration Bill, V.S. McClatchey, chief spokesman for the exclusion forces, summarized the unusual dangers of these “unassimible” immigrants from an emerging world power: “We are forced to consider particularly the case of Japan because Japan has insisted on making her protest against it [the law] on racial and national grounds. Of all the races ineligible to citizenship under our law, the Japanese are the least assimible and the most dangerous to our country.”(note 2)

In the essay that follows, I trace the interaction of anti-Japanese immigration agitation with international events between 1900 and 1924 and particularly focus on the key role of the American labor movement in seeking anti-Japanese legislation. The cry of racial incompatibility was taken up by California unions and by such spokesmen as McClatchey, who represented labor in the successful national exclusion struggle. Although Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor from its inception until 1924, was a Jewish immigrant, he wrote of the dangers of “coolies” as late as 1918, warning that “Chinese workers provoke a conflict between white and yellow standards of life and work in which the coolies supplant and drive out white workers.”3 Alleging that Japanese workers posed the same problem, Gompers and the AFL provided a national forum for the demands of the Chinese and Japanese exclusion movements.

A study of the influence of the anti-immigration movement on US-Japanese relations would add a useful perspective in both world history and American history courses. Such a study illustrates the crucial interplay between foreign affairs and domestic issues. As students focus on the causes of the Pacific War, they will consider how much the immigration controversy affected mutual perceptions of Americans and Japanese, as well as specific negotiations such as the Versailles Treaty talks. For both American and British negotiators at Versailles, it is evident that their ability to compromise was constrained by anti-immigration agitation at home. For Japanese leaders, the issue was largely symbolic. They were less concerned with the terms of the legislation than the racist rhetoric, which, they said, threatened their great power status. This essay will explore the defeat of the racial equality clause proposed by Japan—an example of how promises of democracy and egalitarianism were compromised at Versailles.

In American history courses, teachers expect students to contrast the principle of “all men are created equal” with our history of slavery, racism, and discrimination. By studying Chinese and Japanese exclusion, students learn that racism did not end with the Civil War, nor was it confined to the South. The Exclusion Movement, which marked people of Japanese background as irreversibly different from other Americans, perhaps was a factor in laying the groundwork for public acceptance of Japanese internment camps during World War II.

Chinese Exclusion, Japanese Exclusion, and American Labor: 1900-1924

“The menace of the Asiatic influx is 100 times greater than the menace of the black race, and God knows that is bad enough,” said C.O. Young, special representative of the AFL.4 Most of the themes of the twentieth-century agitation for Japanese Exclusion were foreshadowed in the anti-Chinese or “anti-Mongolian” movement in nineteenth-century America. By 1870, there were 63,000 Chinese, nearly all adult males, in the US, drawn by the discovery of gold. While the bulk of them, 77 percent, lived in California, men found work in the Southwest, New England, and the South as well. By the late 1860s, as the profits in gold decreased, 12,000 Chinese men took on the treacherous task of building the Central Pacific Railroad across the country.5 In early calls for Chinese exclusion, it was evident that Chinese were differentiated from “white” groups, who might eventually be integrated into American society. Like African-Americans and Native-Americans, Chinese were categorized as racially inferior. Even the stereotypes describing these groups were similar. With dark skin and thick lips, Chinese men were “childlike and lustful,” with a passion for white women. Focusing on a young white girl in a Chinese-owned opium den, a New York Times writer reported on a conversation with the owner: “Chinaman always have something to eat, and he like young white girl. He He.”6

From its inception, the American labor movement became the most consistent, vocal, and widespread proponent of Chinese exclusion. In 1881, delegates to the first meeting of the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the US and Canada, a precursor to the AFL, heard San Francisco Cigar Makers Union Chief C.F. Burgman call for the “use of our best efforts to get rid of this monstrous immigration.”7 Burgman,s discussion of the effect of Chinese immigration on California cigar makers impressed another cigar maker, Samuel Gompers, who later became the first president of the American Federation of Labor in 1886. By 1902, Gompers had testified before Congress in favor of the Chinese Exclusion Law, acting with the approval of the 1902 Convention of the AFL. When the law became permanent in 1904, it began to have a negative effect on US-China trade. Reacting to the 1905 Chinese boycott of American goods, President Roosevelt, American business groups, and Chinese leaders identified American labor as the chief source of opposition to compromise.

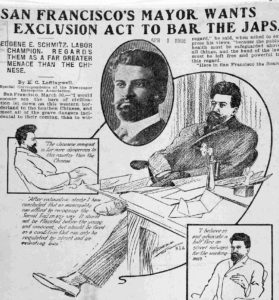

As Japanese immigration increased slightly in the late 1800s, exclusionists began to link Chinese and Japanese immigration. In 1900, the Democratic Party platform called for “a continuance of the Chinese Exclusion Law and its application to the same classes of all Asiatic races.”8 In December, the AFL convention in Louisville, Kentucky, condemned the “suffering of the Pacific Coast resulting from Chinese and Japanese coolie labor.”9 In 1905, the leadership of anti-Japanese agitation in California was taken by the newly formed Japanese and Korean Exclusion League, a group composed of labor organizations almost entirely.

For exclusionists, 1905 represented a turning point as they connected Japanese victories in the Russo-Japanese War with the immigration issue. That year, the San Francisco Chronicle warned that “once the war with Russia is over the brown stream of Japanese immigration will become a raging torrent.”10 Events reached a crisis in 1906 when the Japanese government protested the San Francisco School Board’s order to segregate Chinese, Japanese, and Korean children in public schools. For Roosevelt, Japan’s growing power required sensitivity. The president conducted negotiations between the US State Department, the Japanese ambassador, and the San Francisco School Board that resulted in a compromise known as the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1908. According to the agreement, the school board rescinded the segregation order for Japanese children only. In return, the Japanese government agreed to end Japanese immigration to the US from both the mainland and Hawai`i. Since exclusion was an important goal of the school board, the agreement mollified both sides temporarily. Most historians identify organized labor as providing the crucial leadership in the anti-Japanese agitation in California between 1905 and 1908.

Although Theodore Roosevelt remained cautious about Japanese military power, he felt that Japanese gains in Asia vis-à-vis Russia worked to the advantage of the US. Roosevelt’s 1905 settlement of the Russo-Japanese War, for which he received a Nobel Prize, helped solidify Japanese control over Korea. Fearing that American racism would lead to conflict with Japan, Roosevelt suggested that anti-Japanese agitation in California was “as foolish as if conceived by the mind of a Hottentot,” ironically a racist statement in itself.11 Identifying the cause of the disturbance, Roosevelt wrote “the labor unions bid fair to embroil us with Japan.”12 Concerned about racism in America at the close of the war, Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Tadusu stated, “The anti-Japanese agitation was attributable to irresponsible journalists and labor leaders in certain parts of the United States; it could not conceivably lie deeper.”13

After 1908, the exclusion movement faced no serious threat until the American entry into World War I energized business groups long opposed to severe restriction and exclusion laws. In his 1918 editorial “We Will Win Without Coolies,” Samuel Gompers targeted the steamship companies that had lobbied for a repeal or suspension of the Chinese Exclusion Law. Finding a congressional supporter in Senator Gallinger of New Hampshire, the companies had convinced the senator to present a resolution to investigate such a repeal. To justify the AFL position, Gompers differentiated between European immigrants, who eventually “cooperate” and “coolies,” who do not. He explained that “World experience has demonstrated that the white race cannot assimilate races of other colors—we already have one race problem unsettled.”14 Like many discussions of immigration in the Federationist, Gompers’ editorial began with a discussion of economics and ended with a race-based justification. Ironically, one year later, in May 1919, Gompers was chosen presiding officer of the International Commission for Labor Legislation at Versailles, which offered a list of necessary conditions for a “better life for all workers.”

The next major clash between anti-Japanese immigration forces and US international interests erupted in a controversy over the Japanese proposal for a racial equality clause in the League of Nations Covenant. As the liberal-leaning Japanese negotiators at Versailles—Baron Makino Nobuaki and Viscount Chinda Sutemi—became aware of Wilson’s emphasis on the League of Nations, they added a proposal for a racial equality clause in the league’s covenant to their territorial claims to the Shandong Peninsula in China and the Pacific islands north of the equator. As a partner in the league, the Japanese government felt it would need a guarantee “against the disadvantages to Japan, which would arise . . . out of racial prejudice.”15 Regarding Colonel House—Wilson’s special advisor at Versailles as “pro-Japanese”—Makino and Chinda approached him with the general concept on February 2, 1919. Reacting positively, House assured them that he “deprecated race, religious, and other types of prejudice,” considering them “serious causes of international trouble.”16 Initially, Wilson agreed to present the proposal as part of his own but later bowed out, citing his preoccupation with drafting the league’s covenant. Finally, the Japanese delegates themselves presented the following amendment to Article 21 to the League of Nations Commission on February 13, 1919:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect, making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

Immediately, American and British delegates at Versailles concluded correctly that domestic anti-immigration groups would see that the clause threatened exclusion laws. Historically, President Woodrow Wilson had demonstrated an ambivalent and pragmatic attitude toward race and immigration. In his 1912 bid to win California, Wilson took an unequivocal stand: “In the matter of Chinese and Japanese coolie immigration, I stand for the national policy of exclusion.”17 For the Americans, Britain provided a good amount of political cover by adopting the position of the dominions, particularly Australia, which had adopted a “White Australia” policy.18 At home, the fear that the racial equality clause would interfere with domestic immigration laws united Republican isolationists with anti-Japanese immigration Democrats, such as Senator Phelan of California. On April 11, the day of the vote, Wilson was barraged with telegrams from Pacific Coast politicians, demanding the withdrawal of the racial equality clause. As chair of the League of Nations Commission, Wilson engineered the defeat of the Japanese proposal, managing to save the US from a “no” vote. In spite of a majority vote for the amendment, Wilson stated that “strong opposition,” an obvious reference to Britain and her dominions, precluded its adoption.19

The Japanese reaction to the defeat of the racial equality clause was two-fold. Japanese diplomats and governmental leaders condemned Western racism. At the same time, they used the defeat as a bargaining chip for their aspirations in Shandong. A month before the final vote on the equality amendment, the Japanese ambassador to the US, Ishii Kikujiro, had publicly expressed his government’s opinion of immigration restrictions. At a banquet of the Japan Society, he asked, “When all the restrictions or prohibitions against chattels and commodities are being adequately provided for, why should this unjust and unjustifiable discrimination against persons remain untouched?”20 After the rejection of the equality amendment, Makino spoke prophetically to a plenary session of the Peace Conference on April 28, arguing that the amendment’s rejection would undermine the harmony that was critical for the League of Nations’ success.

Makino found his sentiments shared by his countrymen at home. As Japan took its place at the Peace Conference, Japanese editorials described the meeting as the forum to fight international racial discrimination. When the delegation returned to Japan, a crowd protesting the defeat of the racial equality clause greeted them. Naoko Shimazu’s analysis of three leading Tokyo daily newspapers in Japan, Race, and Equality stressed that the defeat led to disallusionment with the League of Nations and the Anglo-Japanese alliance, as well as a general feeling of isolation from the West and China. Okuma Shigenobu, a popular former prime minister, argued that Japan should not join the league. One important consequence of this defeat, called the “curse of the conference” by Secretary of State Lansing, was the need of the Western powers to placate Japan in order to ensure her signature on the treaty.21 According to Margaret MacMillan,s account in Paris 1919, Makino promised Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, that the Japanese would not protest the racial equality decision at the plenary session if their claims to Shandong were approved. While it is possible that the Japanese were bluffing, the Council of Four approved Japanese concessions in Shandong on April 30, 1919.

After the war, the prevailing revulsion against foreigners in the US reached its final expression in the Immigration Act of 1924, which restricted immigration from all countries. The forces of isolationism were buttressed by pseudo-scientific studies of racism, such as Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race. Since this article has focused on American labor, the most far-reaching force for restriction, it is instructive to consider a detailed piece on “The Japanese in Hawai`i,” published in the American Federationist in October 1922. Certainly, the article by Paul Scharrenberg of the California Federation of Labor combines broader racist currents with specific fears of Japan as a rising power, looking for lebensraum (living space) for her people. Whether accurate or not, Scharrenberg provides statistics showing that the Japanese population of Hawai`i was increasing rapidly in spite of the Japanese government’s promise to honor the Gentleman’s Agreement on the island. Because of picture brides and the immigrant’s ability to bring over family members, voters of Japanese blood would reach the point of numerical majority between 1940 and 1950.22 Moreover, Scharrenberg cautioned that the foreign culture was beginning to predominate. According to his study, over half of the school population attended foreign language schools in which the Japanese language, history, institutions, manners, customs, and religious ideas were taught. He noted that Honolulu had four Japanese-language daily newspapers that celebrated the expansion of the empire and advocated free immigration. Implying that the Japanese were more interested in colonizing than assimilating, Scharrenberg asserted that the vision of Hawai`i as a melting pot of races was sentimentalism because “Caucasians and the Japanese are not of the same racial stock.” He concluded with a call for the replacement of the Gentleman’s Agreement with an exclusion law.

In spite of the prevailing sentiment favoring immigration restriction in 1924, no widespread support existed for the principle of Japanese exclusion. In March, at a meeting of the Senate Committee on Immigration, V.S. McClatchey, publisher of The Sacramento Bee, testified on behalf of the American Federation of Labor, the American Legion, the National Grange, and the Native Sons of the Golden West. According to these organizations, the proposed comprehensive immigration law should contain a clause excluding aliens ineligible for citizenship. Since Chinese had already been excluded by law, the coalition presented a clause that specifically targeted Japanese. McClatchey based his argument on racial grounds and related problems of national security, familiar themes in AFL literature. According to McClatchey, of all Asian immigrants, the intelligence and perseverance of the Japanese made them the most dangerous. He suggested the security threat posed by an aspiring world power, which sent its people to “colonize this country by getting children and getting land,” while maintaining control over Japanese immigrants.23

On the floor of the Senate, David Reed, author of the National Origins Plan, led the opposition to the exclusion clause. During the debate, the Japanese ambassador, Hanihara, gave Secretary of State Hughes the famous note warning of the grave consequences of the proposed law. Presenting the note as a “veiled threat,” Henry Cabot Lodge led a spirited discussion that resulted in a total reversal of the Senate’s position. The Senate approved the exclusion clause seventy-one to four. Despite Secretary Hughes’ opposition, the exclusion clause easily won acceptance in the House of Rep resentatives, where the chairman of the Immigration Committee was Albert Johnson of the state of Washington, an enthusiastic racist who vehemently disliked the Japanese. The Japanese exclusion clause aroused more opposition within the US than did the 1924 Immigration Act as a whole. Forty of forty-four major eastern newspapers supported the condemnation of Japanese exclusion by the Coolidge administration. American religious groups and members of the academic community testified against the inherent racism in the law. At its annual meeting in 1924, the National Association of Manufacturers criticized the methods used by Congress to pass the exclusion clause.

In Japan and in the Japanese-American community, government leaders, as well as liberal and conservative parties and ordinary citizens, expressed outrage at this perceived insult, coming at a time when American culture was still popular in Japan. Until July 1, the Japanese government pressured President Calvin Coolidge to veto the bill. When he signed it, Nationalist Tokutomi Soho declared July 1 “National Humiliation Day.” Nitobe Inazo, the Japanese representative to the League of Nations, who was a Quaker married to an American woman, vowed never to set foot on American soil until the law was revoked. At the grassroots level, right-wing organizations, women’s organizations, and Christian groups organized rallies that attracted thousands of people in Tokyo, Osaka, and many smaller cities. Many stores advertised that they did not stock American goods, and women with American hairstyles were accosted.

The Japanese exclusion clause aroused more opposition within the US than did the 1924 Immigration Act . . . Forty of forty-four major eastern newspapers supported the condemnation of Japanese exclusion . . . American religious groups and members of the academic community testified against the inherent racism in the law. At its annual meeting in 1924, the National Association of Manufacturers criticized the methods used by Congress to pass the exclusion clause. . .

Reflections: Japanese Immigration, American Racism, and International Relations

The story of Japanese immigration and American labor becomes part of the American narrative of conflict between egalitarian ideals and economic imperatives. Because the American Federation of Labor was formed to promote the rights of all working people, the organization’s unabashedly racist attitude toward Chinese and Japanese immigrants seems particularly ironic. As we review its literature in the last part of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth, it is evident that the American labor movement assumed an important role in defining Chinese and Japanese immigration as a racial problem as well as an economic one. Using racial incompatibility as a justification, labor provided leadership for a political movement that portrayed Chinese and Japanese immigrants as different. Consistently, the writings of labor leaders denied that these specific immigrants could assimilate as part of the melting pot. Moreover, official labor organizations popularized pejorative racist terms such as “coolies.” In the October 1907 Federationist, an article referred to Japanese as “similar to Darwin’s missing link.” By comparison, AFL literature did not promote the concept of Anglo-Saxon superiority prevalent in the 1920s, nor did it publish racist depictions of African-Americans. Promoting the exclusion clause of the 1924 Immigration Act, American labor and its coalition saw that the definition of Japanese as “other” or “aliens ineligible for citizenship” was written into law. Moreover, this coalition won the racial equality and exclusion controversies in opposition to Presidents Roosevelt, Wilson, and Coolidge, as well as to most elements of the business community.

Certainly, the pseudo-scientific racism prevalent in the West from the mid- and late nineteenth century influenced labor and other exclusionists, whose natural allies were Southern segregationists. In the case of twentieth-century Japan, the country’s position as a rising world power added the specter of a national security threat to their argument. While the connection between anti-Japanese immigration agitation, American labor, and the resulting Japanese exclusion law is well-documented, it is less clear how the immigration controversy influenced Japanese foreign policy, especially its relationship with the US. From the beginning of the century through the 1920s, we have numerous examples of official protests, Japanese newspaper editorials, public demonstrations, and boycotts of American goods. As they aspired to great power status, the Japanese objected to the stigma of racial inferiority even more than to the immigration limit. Even more insulting was being grouped with the Chinese to whom, at this point, they felt superior. The rejection of the 1919 racial equality clause represented a turning point in the American-Japanese relationship. If Woodrow Wilson, creator of the League of Nations, would not confront the exclusion lobby, then what American politician would resist domestic pressure to support universal principles? There is evidence that the politics of race at Versailles influenced the Western decision to concede Shandong to Japan. The Immigration Act of 1924 delivered a stinging racial insult at a time when American political culture still had adherents in Japan. Certainly, America’s exclusion policy affected mutual perceptions of Japan and America in the years leading to World War II. In Japan, exclusion buttressed right-wing nationalists, who argued that Japan was not accepted by the West and must, therefore, pursue her own interests. In America, it helped lay the groundwork for racist depictions of the Japanese during the war as well as the treatment of Japanese-Americans as aliens.

Primary Sources for Possible Classroom Use

Immigration Act of 1924

Author Note: There is no direct reference to Japanese exclusion. It was accomplished in an indirect way. The law excluded “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” a designation applied to Japanese in a 1922 Supreme Court case. C.J. Fenwick, The American Journal of International Law 18, no. 3, July, 1924: 518–523. Section 13(c) of the law provides that:

No alien ineligible to citizenship shall be admitted to the United States . . . the naturalization laws of the United States were from the beginning limited to “free white persons,” the only subsequent modification being made in 1875 in favor of aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent. After a series of decisions in the lower courts, in which the term “white persons” was interpreted to mean persons of what is popularly known as the Caucasian race,the Supreme Court of the United States finally decided on November 30 1922, in the case of Ozawa vs. the United States, that “one who is of the Japanese race and born in Japan” was not eligible for citizenship.

Policy of San Francisco School Board

Herbert B. Johnson, Discrimination Against the Japanese in California, Action of San Francisco Board of Education, May 6, 1905 (Berkeley: Courier Publishing Co., 1907).

The Board of Education is determined in its efforts to effect the establishment of separate schools for Chinese and Japanese pupils, not only for the purpose of relieving the congestion at present prevailing in our schools, but also for the higher end that our children should not be placed in any position where their youthful impressions may be affected by association with pupils of Mongolian races.

Racial Equality and Treaty of Versailles

Racial Equality Clause: Original Proposal to the League of Nations Commission on February 13, 1919, as an amendment to Article 21(religious freedom).

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the league, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or fact, on account of their race or nationality

in Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race, and Equality (London: Routledge, 1998).

Notes

- Roger Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice (New York, Atheneum, 1972), 111.

- United States Senate Committee on Immigration, Japanese Immigration Legislation (Washington, DC: March 11, 1924), 3.

- Samuel Gompers, American Federationist XXV, Part 1, January 1918: 60.

- Daniels, 16.

- Ronald Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), 79.

- Takaki, 101.

- Philip Taft, Organized Labor in American History (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1964), 303.

- Daniels, 22.

- Ibid.

- Daniels, 25.

- Akira Iriye, Across the Pacific (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, Inc., 1967), 99.

- Thomas A. Bailey, Theodore Roosevelt and the Japanese-American Crises (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1934), 28.

- Iriye, 114.

- Ibid.

- Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race, and Equality (London: Routledge, 1998), 17.

- Ibid.

- Woodrow Wilson to James D. Phelan, quoted in Kristofer Allerfeldt, “Wilsonian Pragmatism? Woodrow Wilson, Japanese Immigration, and the Paris Peace Conference,” Diplomacy and Statecraft 15, no. 3 (Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis, 2004), 545–572.

- Shimazu, 30.

- Ibid.

- Allerfeldt, 362.

- Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (New York: Random House, 2003), 338.

- Paul Scharrenberg, “The Japanese in Hawai`i,” The American Federationist 29, 1922: 744.

- Ibid, 749.