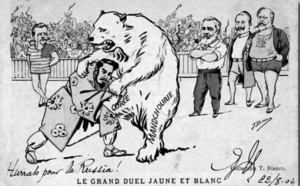

Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yellow_Peril.

The term “The Yellow Peril” has long since passed out of fashion, but it was a widely used expression in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The nightmare of wild oriental hordes swarming from the East and engulfing the “civilized” societies of the West was a popular theme in literature and journalism of the time. Yellow Peril supposedly derives from a remark made by German Kaiser Wilhelm II following Japan’s defeat of China in 1895 in the first Sino-Japanese War. The expression initially referred to Japan’s sudden rise as a military and industrial power in the late nineteenth century. Soon, however, it took on a more general meaning embracing the whole of Asia. Writing about the Yellow Peril encompassed a number of topics, including possible military invasions from Asia, perceived competition with the white labor force from Asian workers, the supposed moral degeneracy of Asian people, and fears of the potential genetic mixing of Anglo-Saxons with Asians.1

Image source: The Berkeley Digital Library Sunsite as

http://london.sonoma.edu/cgi-bin/londonimages.pl? keyword=

Jack+London.

Jack London (1876–1916), one of the most famous and prolific American writers and journalists at the start of the twentieth century, is often associated with the term Yellow Peril. London today is most often associated with his Klondike classics, The Call of the Wild and White Fang, and such rousing adventure classics as The Sea-Wolf, but he devoted much of his later literature and essays to Pacific and Asian affairs and was also one of the major socialist activists, theoreticians, and politicians of his era.2 Teachers and students of world and American history and literature should examine London’s work, not only because of his influence as one of the leading writers and journalists of the early 1900s, but also because of his efforts to combat the anti-Asian sentiments found in American journalism during this period. The goal of this article is to introduce London the internationalist— someone who respected Asians and who, through his stories and articles, endeavored to give readers a much more realistic picture of the Japanese and Chinese than he encountered in other writings.

London, a native Californian, lived during a time when white Americans in his state repeatedly rioted against the many Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans who had settled there in the late nineteenth century. Other writers and journalists of the time gave very unflattering views of Asians, or touted white Anglo-Saxon superiority over the yellow and brown people of Asia. The huge chain of American newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst frequently used the term Yellow Peril in a derogatory manner, as did noted British novelist M. P. Shiel in his short story serial, The Yellow Danger. One also finds similar views in Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” and throughout his stories and novels.

One of the major problems facing the West, London surmised, was that Westerners, living in their self-contained, ignorant bliss, had no understanding of Asian cultures and were far too confident of their superiority to realize that their days of world power were numbered.

Several scholars in the late twentieth century miscast London as a proponent of Yellow Peril racism. John R. Eperjesi, a scholar of London’s work, writes that “More than any other writer, London fixed the idea of a yellow peril in the minds of the turn-of-the-century Americans . . . .”3 Many biographers quote London, just after his return from covering the first few months of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) for Hearst newspapers, as telling a coterie of fellow socialists of his profound dislike for the “yellow man.” Biographer Richard O’Connor quotes Robert Dunn, a fellow journalist with London during the Russo-Japanese war, as saying that Jack’s dislike of the Japanese “. . . outdid mine. Though a professed Socialist, he really believed in the Kaiser’s ‘yellow peril.’”4

Despite these comments, a close examination of London’s writing indicates that he was anything but an advocate of the racist yellow peril writing. London, perhaps the most widely read and famous journalist covering the Russo-Japanese War, emerged as one of the few internationalist writers and newspaper photographers of his day who realized that the heyday of white superiority, Western expansionism, and imperialism was coming to an end. Also, his positive views towards Asians emerged a decade earlier in his first published stories. London first visited Japan in 1893 as a seventeen-year-old aboard the sealing ship Sophia Southerland. His first four short stories about Japan, published soon after his return, portray its people in a sympathetic light. London was critical of Japanese officials and censors during the Russo-Japanese War, but his correspondence on Japanese soldiers and Chinese and Korean civilians was very sympathetic.

After his return from Manchuria in 1904, and until his death in 1916, London’s writings show increasing concern and admiration for the people of Asia and the South Pacific. He very accurately predicted that Asia was in the process of waking up, and that countries like Japan and China would emerge as major economic powers with the capacity to compete with the West as the twentieth century progressed. London also declared that Westerners must make concerted efforts to meet with Japanese and Chinese, so that they could begin to understand each other better as equals.5

Jack London had a greater understanding of the profound changes occurring throughout the industrial world in the early twentieth century than most writers of the period. His fiction and essays explored questions of the changing aspects of modern warfare, industrialization, revolution, and Asia’s rise to world power. London also shrewdly predicted the shape of political and economic power throughout the twentieth century—including the coming of total war, genocide, and even terrorism–that makes much of his writing as relevant today as when it was first composed.6

For London, and for other writers of the time, Russia’s defeat by Japan was a critically important turning point in the way the American press represented Asians; journalists began to challenge the long-held belief in the innate superiority of the white race.

LONDON’S PREDICTION

CONCERNING THE ECONOMIC

RISE OF EAST ASIA

During and after his time in Korea and Manchuria, London developed a thesis that postulated the rise, first of Japan and then of China, as major twentieth century economic and industrial powers. London suggested that Japan would not be satisfied with its seizure of Korea in the Russo-Japanese War, that it would in due course take over Manchuria, and would then seize control of China with the goal of using the Chinese with their huge pool of labor and their valuable resources for its own benefit. Once awakened by Japan, however, the Chinese would oust the Japanese and rise as a major industrial power whose economic prowess would cause the West so much distress, by the mid-1970s they would launch a violent attack on China to remove them as economic threats.

(1904–05), at http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/yellow_promise_yellow_peril/yp_essay04.html.

The past few decades have witnessed the rise of East Asia. First Japan, then later South Korea, and China have experienced a tremendous growth of wealth and power. East Asia’s surge has been largely economic, but its newfound status has effectively challenged the economic status of the United States and Europe. China’s new wealth has permitted modernization of its army and navy, causing many American, European, and Japanese leaders, scholars, and writers to question China’s intentions. The Chinese claim that they are strengthening their military capacity for self-defense, including the protection of sea lanes to the oil rich Middle East, but American and Japanese strategists voice concern over China’s ability to overturn the current balance of power in East Asia.

Jack London, writing a full century ago, foresaw this development with incredible accuracy. He warned that the West was living in a bubble—that its incredible power and wealth, and its tenacious hold on Asia, would burst in due course, and that the center of world power would shift to East Asia. London predicted that initially the transition would be peaceful, because Asia’s rise would be primarily economic, but in the end, war between East and West would be inevitable. London predicted that Western nations, terrified of China’s rising power, would unite and together do its utmost to savagely wipe out Chinese civilization.

One of the major problems facing the West, London surmised, was that Westerners, living in their self-contained, ignorant bliss, had no understanding of Asian cultures and were far too confident of their superiority to realize that their days of world power were numbered. In dispatches from Korea and Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War, and in several postwar essays, London analyzed the potential of the three major cultures he encountered, and predicted which ones would rise to world dominance. For London, and for other writers of the time, Russia’s defeat by Japan was a critically important turning point in the way the American press represented Asians; journalists began to challenge the long-held belief in the innate superiority of the white race.7

London made a clear distinction between the Chinese and the Japanese. He labeled the Chinese as the Yellow Peril and the Japanese as the Brown Peril. Even though Japan was on the ascent in 1904–1905, while China was moribund, London was confident that in the end, Japan lacked both the size and the spirit to lead an Asian renaissance. That task would devolve to China. He predicted that Japan would launch a crusade crying “Asia for the Asiatics,” but that their contribution would be to act as a catalyst that would awaken the Chinese. He believed Japan would become strong because of its ability to learn to use Western technology, and because they were united as one people, but London suggests that there are severe limits to how far Japan could go in realizing the objective. According to London, the first factor inhibiting Japan was that

No great race adventure can go far nor endure long which has no deeper foundation than material success, no higher prompting than conquest for conquest’s sake and mere race glorification. To go far and to endure, it must have behind it an ethical impulse, a sincerely conceived righteousness.8

The second inhibiting factor was Japan’s small size and population. A century ago, it was estimated that there were forty-five million Japanese—enough to hurl back Russia’s Imperial forces, but not enough to create a massive Asian empire or to militarily or economically threaten the Anglo-Saxon world. Seizing “. . . poor, empty Korea for a breeding colony and Manchuria for a granary . . . ” would greatly enhance Japan’s population, but even that would not be enough. “The menace to the Western world lies, not in the little brown man, but in the four hundred millions of yellow men should the little brown man undertake their management.”9

London’s 1904 essay “The Yellow Peril” leaves readers hanging. Japan has demonstrated its capacity to defeat a major world power, Russia, but is not strong enough to achieve its dream of an “Asia for the Asiatics.”

London pointed out that the entire white population of Europe and North America, was still outnumbered by Chinese and Japanese. Just as the West was engaged in an adventure to expand its power around the world, what would prevent the Japanese and Chinese peoples from having similar dreams of wealth and conquest? Critics questioned how it would be possible to awaken China. The West had been trying to do just that for many decades and had failed. Then, how could the Japanese succeed? London’s rather sophisticated response was that the Japanese better understood the Chinese because they had built their country on an imported foundation of Chinese culture.

London’s 1904 essay “The Yellow Peril” leaves readers hanging. Japan has demonstrated its capacity to defeat a major world power, Russia, but is not strong enough to achieve its dream of an “Asia for the Asiatics.” Before Japan lay Manchuria, with all of its resources, and beyond that was China proper, with its four hundred million hardworking citizens. China’s potential as a world power is restricted by its literati leaders, who cling to power by embracing a conservatism that holds tenaciously to the past and refuses to let their country modernize. London does not tell the reader who will prevail as the great power in Asia, but his 1906 short story, “The Unparalleled Invasion” provides the answer—China.

China, with its endless resources and huge, skilled, hardworking population, would be the factory workshop that would provide Japan with the wealth and power she desired. But in taking over China, Japan would have to eradicate China’s conservative leadership that had held her back so long. The Chinese, free at last from the tyranny of their decrepit leadership, could either accept the Japanese or fight them off and develop their own industrial and military might. A resurgent China would directly challenge the economic might of the West.

“The Unparalleled Invasion” is a futuristic horror story involving a major world war, incredible genocide, and the annihilation of Chinese civilization. Although critics have read different messages from what they believe London is telling them, the irony here is that the West is the paranoiac aggressor, and China the innocent victim of this paranoia. London’s story is a stern warning about what can happen if racial hatred is allowed to flourish. London was writing at a time when the modern concept of germ warfare was being considered by various nations (it reached its fruition in World War I). Here London sounds an alarm over the potential hazards of biological warfare. The story is an ironic indictment of the behavior of imperialistic governments.

The Japanese are expelled from China and are crushed when they try to reassert themselves. But, “contrary to expectation, China did not prove warlike…[so]…after a time of disquietude, the idea was accepted that China was not to be feared in war, but in commerce.” The West would come to understand that the “real danger” from China “. . . lay in the fecundity of her loins.” Nevertheless, as the twentieth century advanced, Chinese immigrants swarm into French Indochina, and later into Southwest Asia and Russia, seizing territory as they expand. Western attempts to slow or stop the Chinese expansionism all come to naught. By 1975, it appears the world will be drowned by this relentless Chinese expansion.

Image source: Gusts of Popular Feeling Blog at http://populargusts. blogspot.com/search?q=jack+london.

Just as the West was beginning to despair, an American scientist, Jacobus Laningdale, visits the White House to propose the idea of eradicating the entire Chinese population by dropping deadly plagues from Allied airships flying over China. Six months later, in May 1976, the airships appeared over China dropping a torrent of glass tubes. At first, nothing happened, but within weeks China was hit by an inferno of plagues, gradually wiping out the entire population. Allied armies surrounded China, making it impossible for anybody to escape the massive deaths. Even the seas were closed by 75,000 Allied naval vessels patrolling China’s coast. “Modern war machinery held back the disorganized mass of China, while the plagues did the work.”10

The reader sees that vast cultural differences divide the West from China, and it is these differences that cause hatred and malice from the West. The focus here is not on the dangers that China presents the West, but, rather, the reverse. As Jean Campbell Reesman candidly points out, “London’s story is a strident warning against race hatred and its paranoia, and an alarm sounded against an international policy that would permit and encourage germ warfare. It is also an indictment of imperialist governments per se.”11

London’s increasingly pan-national view of the world led to his 1915 recommendation for a “Pan-Pacific Club” where people from both East and West could meet in a congenial setting. The “club” would be a forum where East and West could exchange views and ideas on an equal basis.

LONDON THE INTERNATIONALIST

In Unparalleled Invasion and in two essays, London urges that the West come to terms with the new Asia. London presumes that the wars of the twentieth century will greatly surpass those of the past in terms of death and destruction, not only of armies, but of civilian populations, as well. He hated war and needless violence, and again warns readers against what did happen in World Wars I and II.

There is a marked refinement of London’s views towards Asians and other non-white people of the Pacific in the last seven years of his life, following his 1907–1909 voyage to the South Pacific aboard his schooner the Snark. London’s increasingly pan-national view of the world led to his 1915 recommendation for a “Pan-Pacific Club” where people from both East and West could meet in a congenial setting. The “club” would be a forum where East and West could exchange views and ideas on an equal basis. These are hardly the thoughts of a racist; rather, they are the words of a true internationalist. He resolved that Hawai`i was the ideal place for this encounter to take place.

In one of his last essays, “The Language of the Tribe,” London described what he perceived to be some of the reasons for cultural misunderstanding between Japanese and Americans. He saw the Japanese as a patient and calm people, while Americans were hasty and impatient. These and other extreme differences have made it difficult for Americans to understand the Japanese and difficult to accept their immigrants to the United States as citizens. There had to be a place where both Americans and Japanese could come together and better understand their respective cultures: He wrote:

A Pan-Pacific Club can be made the place where we meet each other and learn to understand each other. Here we will come to know each other and each other’s hobbies; we might have some of our new made friends of other tribes at our homes, and that is the one way we can get deep down under the surface and know one another. For the good of all of us, let’s start such a club.12

CONCLUSION

Jack London traveled extensively during his short life. He encountered people of many cultures and empathized with the suffering of the downtrodden, not only in the United States, but also in Europe, East Asia, and the South Pacific. London, unlike many writers of his time, was an internationalist who made a genuine effort to get to know the people and cultures in the lands he traversed. His “Pan-Pacific Club” essay is his final appeal for the West to remove its stereotypical view of Asians as inferior peoples who needed Western domination for their own good.

NOTES

1. See William F. Wu, The Yellow Peril: Chinese-Americans in American Fiction, 1850–1940 (Hamden CT: Archon Books, 1982).

2. London twice ran for mayor of Oakland California as a Socialist.

3. John R. Eperjesi, The Imperialist Imaginary: Visions of Asia and the Pacific in American Culture (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth University Press, 2005), 108.

4. Richard O’Connor, Jack London: A Biography (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1964), 214.

5. London developed these ideas while covering the early stages of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) in Korea and Manchuria. London was stunned to find Asians using the most up-to-date Western technology, military methodology, and weapons of mass slaughter with great proficiency. He published these ideas in two articles “The Yellow Peril” in the San Francisco Examiner, 25 September 1904; and “If Japan Awakens China” in Sunset Magazine, December 1909 and one short story, “The Unparalleled Invasion” McClure’s Magazine, May 1910.

6. Jonah Raskin, a professor at Sonoma State University, provides an interesting analysis of the relevance of London’s writing a century after his death: “In a short, volatile life of four decades, Jack London (1876–1916) explored and mapped the territory of war and revolution in fiction and non-fiction alike. More accurately than any other writer of his day, he also predicted the shape of political power—from dictatorship to terrorism—that would emerge in the twentieth century, and his work is as timely today as when it was first written.” Jonas Raskin, ed., The Radical Jack London: Writings on War and Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 1.

7. John R. Eperjesi, The Imperialist Imaginary: Visions of Asia and the Pacific in American Culture (Hanover NH: Dartmouth University Press, 2005), 109.

8. Jack London Reports, 346.

9. Ibid.

10. Jack London, “The Unparalleled Invasion” in Dale L Walker, Ed., Curious Fragments (Port Jefferson NY: Kenkat Press, 1976), 119.

11. Jeanne Campbell Reesman, Jack London: A Study of the Short Fiction (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1999), 91.

12. Jack London, “The Language of the Tribe,” in Mid-Pacific Magazine, August 1915. Reprinted in Daniel J. Wichlan, Jack London: The Unpublished and Uncollected Essays (Bloomington IN: AuthorHouse, 2007), 126.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LONDON’S

WRITING ON ASIA

King Hendricks and Irving Shepard, Jack London Reports: War Correspondence, Sports Articles and Miscellaneous Writings (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1970). This work contains London’s entire correspondence and articles from his coverage of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, plus his very hard to find articles, “The Yellow Peril” and “If Japan Awakens China.”

The following novels and short stories by Jack London focus specifically on Asia and are available online or in various scattered anthologies: “Story of a Typhoon off the Coast of Japan,” “Sakaicho Hona Asi and Hakadaki,” “O Haru,” “A Night Swim in Yeddo Bay,” “Chun Ah Chun,” ”Koolau the Leper,” “The Unparalleled Invasion,” “The Star Rover,” and “Cherry.”

For further background reading, see Jeanne Reesman, Jack London’s Racial Lives (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2009) and Daniel A. Métraux, “Jack London’s Influential Role as an Observer of Early Modern Asia” in the Southeast Review of Asian Studies (30) 2008, available on line at http://www.uky.edu/Centers/Asia/SECAAS/Seras/2008/2008TOC.html.