As governor of Osaka Prefecture, and later mayor of Osaka city, Tōru Hashimoto was faced with significant debt accruing from annual budget deficits. To address this, he assertively promoted competition, private business, and reduction of public funding for the arts. He felt strongly that “what users don’t choose basically shouldn’t be provided” and, accordingly, believed that arts organizations such as the Osaka Symphony Orchestra and National Bunraku Theater should be self-supporting.1 As mayor of Osaka, he attended a performance of Sonezaki Shinjū (The Love-Suicides at Sonezaki) in 2012. Written in 1703 by master playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1725), Sonezaki Shinjū remains one of the most celebrated plays in the repertoire of bunraku, the Japanese traditional puppet theater. Hashimoto was not impressed, however. In addition to feeling that public funding was inappropriate, he also seemed to harbor a personal distaste for bunraku—he had previously vowed never to attend another performance and spoke dismissively of Sonezaki: “I understand this is an art that should be preserved as a classic, but the last scene was plain, and lacked something . . . The staging was unsatisfactory. Does it really have to follow the old script that precisely?”2 In addition to finding the National Bunraku Theater stodgy and old-fashioned, Hashimoto was also suspicious of the Bunraku Kyōkai, a semi-governmental agency that manages bunraku performers, which he felt operated without sufficient transparency.3 Shortly after the performance, he cut the association’s subsidy by 25 percent to ¥39 million (approximately US $347,000), and in the years following, he granted funding only if specific attendance targets were met. In 2013, attendance was below the target, and accordingly, the subsidy was reduced to ¥32 million (approximately US $285,000).4

Hashimoto’s attitude seems to reflect a broader trend in recent Japanese culture, which finds traditional music and drama generally less useful in shaping the sense of self. Simon Frith, sociologist and chair of music at the University of Edinburgh, has argued that rather than reflecting the culture that produces it, music actually produces culture by providing an experience that allows its audience to understand themselves differently and place themselves within a cultural narrative.5 While the Japanese music industry has grown to the second-largest in the world, popular music styles derived from a spectrum of international sources have seemed generally to provide experiences more useful for the formation of modern, cosmopolitan identities. While traditional music and the deeply musical genres of Japanese theater still speak to universal themes, they no longer seem to provide experiences as effective for contemporary Japanese. While Hashimoto’s budget cuts represent the most recent instance of this loss of utility, however, they are hardly the first. In an era that potentially challenges its continued viability, hopefully readers who are supportive or at least open to the value of the traditional arts will be better informed or intrigued enough by the introductory essay that follows to learn more about this classic form of Japanese theater—or even become preservation advocates.

Bunraku developed from several genres of accompanied narrative music collectively called jōruri, after the popular epic Jōruri-hime monogatari (Tale of Princess Jōruri). As the genre developed, performers added puppets, or ningyō, to illustrate the action. The musical component of this new ningyō-jōruri became increasingly sophisticated and eventually separated into specialized roles: the tayū, or chanter, who described the settings, narrated the action, and provided voices for the characters; and the shamisen player, who supplied all the accompanying music. This music came to consist of a collection of standard melodic formulas that could be either structural, indicating the beginning and ending of sections, or characteristic, evoking particular moods and images. Broadly known as senritsukei, these melodic formulas were used consistently across a broad repertoire of narratives, and frequently named.6

Ningyō-jōruri assumed the characteristic form that would later be called bunraku through the collaboration between tayū Takemoto Gidayū (1651–1724) and playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1725) in 1684. Their new puppet theater, the Takemoto-za, played a significant role in the culture of Osaka for about eighty years. Chikamatsu’s plots, even in his historical dramas, featured realistic relationships between middle-class characters and their loyalty to family and close friends, particularly as it clashed with their loyalty to social superiors, which resonated strongly with Osaka natives.7 Furthermore, Chikamatsu’s contemporary dramas were drawn from recent local events: Sonezaki Shinjū itself was based on an actual incident and was staged within a month of its occurrence.8 In bunraku, middle-class merchants of Osaka not only recognized themselves in the characters, but also found their beliefs and struggles clearly articulated, which seems to have given shape to their sense of who they were—in effect, contributing to the formation of their identity.

Gidayū’s distinctive style, called Gidayū-bushi, became synonymous with the music for ningyō-jōruri, and its popularity led his erstwhile protégé Toyotake Wakadayū (1681–1764) to open a rival theater, the Toyotake-za, in 1703. The resulting competition fostered ongoing innovation within the new art form. As bunraku aficionado Barbara Adachi describes:

The chanter and musician first performed on a platform near stage center where they were hidden, with the puppeteers, behind an opaque curtain. Subsequently edged far stage left, they first appeared in full view of the audience on the right-hand side of the stage in 1705. The two were finally given their own auxiliary stage, the yuka, in this stage-left area in 1728, and the increased main-stage area was used for more elaborate sets.

By 1725, the eyes and mouths of the dolls could open and close, and hands could move. Fingers were further articulated in 1733. A year later, puppeteer Yoshida Bunzaburo devised the three-man system of manipulating puppets, which is still used for today’s much larger dolls, and performers vied to outdo each other in skill and dramatic efforts.9

The three-man system (sannin-zukai) mentioned previously is a close collaboration between a master puppeteer, who manipulates the head and right arm of the puppet, and two assistants, one of which controls the left arm and the other the feet. Originally, all three puppeteers wore black robes and hoods in order to appear invisible to the audience. Today, while the assistants still wear black, the master puppeteer performs in a formal kamishimo (an outfit consisting of a formal kimono, a sleeveless top [kataginu], and trousers [hakama]) with his head uncovered, although his face remains impassive throughout the performance. The coordination required in bringing a single character to life is remarkable enough, but the artistry involved when two or more characters interact is nothing short of astonishing.

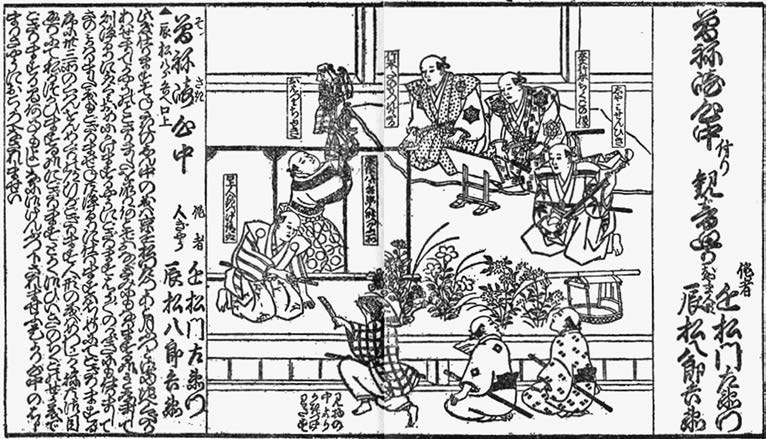

By the 1740s, the puppet theater had reached a “golden age.” Playwrights including Takeda Izumo II (1691–1756), Namiki Sōsuke (1695–1751), and Miyoshi Shōraku (1696–1775) followed Chikamatsu; and worked in teams to create masterworks such as Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami (The Secrets of Sugawara’s Calligraphy) and Kanadehon Chūshingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers), which remain in the standard repertoire today. Many plays were also adapted to the kabuki theater, which owes about half its repertoire to bunraku. The plays even gained considerable prestige as literature; they were published, sometimes with illustrations, and widely read.10 Unfortunately, this success proved short-lived. In the second half of the eighteenth century, with innovations in kabuki staging and the deaths of some of bunraku’s finest performers, the puppet theater was eclipsed by its erstwhile imitator.11 Both the Takemoto-za and Toyotake-za were forced to close by 1767.

In spite of this loss, Gidayū-bushi survived into the nineteenth century through communities of amateur performers. While the subjects of the classic plays no longer reflected the lives of the middle class as cogently, first-hand experience of performing the music seemed to enable enthusiastic amateurs to define themselves as discerning aesthetic connoisseurs. As Shizuo Gotō, former director of the National Theater, describes, the focus of the plays moved from the text itself to the distinctive styles of individual performers.12 Uemura Bunrakuken (1751–1810), a tayū originally from Awaji, catered to these new amateur connoisseurs by opening a jōruri school in Osaka in 1800.13 Nine years later, he was able to form his students into a professional company and began staging performances on shrine grounds. Bunrakuken’s company was essentially a repertory theater: since the cultural value of bunraku seems to have been tied to the demonstration of aesthetic refinement, new plays and further innovations were largely unnecessary. While some new plays were added to the repertoire, they generally following the old traditions.

Bunrakuken ultimately became synonymous with ningyō-jōruri; in 1872, when his artistic descendants opened a theater in the Matsushima neighborhood, they named it the Bunraku-za in his honor, and the art form came to be called simply “bunraku.” Bunraku appears to have proved so effective as a signifier of cultural superiority that it remained vital through the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), in spite of the general adoption of European music and culture. In 1883, public support was strong enough that a group of performers was able to break away and form the Hikoroku-za, opening their own theater the following year. The resulting competition between the elegant Bunraku-za and its more flamboyant rival served to elevate performance standards even further.

Bunraku once again fell on hard times in the twentieth century, however. The Hikoroku-za closed in 1893, and by 1909, the Bunraku-za performers found themselves so financially embarrassed that they were obliged to sell all assets, including the theater itself and the collection of puppet heads, costumes, and props, to the Shōchiku entertainment conglomerate.14 In 1926, this was all destroyed in a fire. Upon opening a new theater in 1930, the Shōchiku introduced the custom, generally maintained to the present day, of performing collections of favorite scenes from the classic plays, rather than complete performances of single plays, with the hope that shorter programs with more variety would improve attendance. In an economic climate hampered by the Great Depression and the beginning of the invasion of Manchuria, however, this met with limited success. In 1933, Japan’s national legislature, the Diet, created a subsidy to help ensure the survival of bunraku.

With the American bombing of Osaka in 1945, the theater, puppet heads, costumes, and props were destroyed a second time.15 The Shōchiku was able to rebuild by 1946, but a general atmosphere of disillusionment in Japan during the post-war period once again robbed bunraku of its cultural value. Musicologist Luciana Galliano, among others, describes the emergence of a “new feeling, that perhaps the West was after all superior to Japan not only technically but also morally.”16 If traditional culture and values had led to defeat and occupation, fluency in its conventions and sensitive appreciation of its nuances would have no prestige. While the artistry of the performers remained consistently high, Japanese literature scholar Donald Keene describes bunraku of the early 1950s largely as a neglected haunt of the elderly. In addition, the theater itself was divided. While older performers felt a sense of loyalty to the Shōchiku, their younger colleagues felt dissatisfied with working conditions under the conglomerate. These groups coalesced into factions: the Chinami-kai remained with the Shōchiku and continued performing at the Bunraku-za, while the Mitsuwa-kai, essentially a labor union, performed as a touring company, frequently appearing as an attraction in Mitsukoshi department stores.

In an effort to make the theater profitable, the Shōchiku revived some classic Chikamatsu plays that had fallen into obscurity, including Sonezaki Shinjū, and also introduced sixty-one new plays between 1947 and 1962, when they finally divested.17 Most of these new productions were created in the 1950s and, along with original plays, included adaptations of works from the kabuki theater, contemporary novels, and such Western dramas as Madame Butterfly, Hamlet, and La Traviata. The new plays were both ambitious and expensive. While traditional bunraku characters are archetypes and the carved heads are reused from production to production, several of the new plays required unique heads to represent familiar historical figures or Western characters (such as Hamlet), which had to be specially carved for each production and could not be used in any other play.18 As none of the new plays survived into the standard repertory, the expense was especially painful.

Stanleigh Jones, Professor Emeritus of Japanese at Pomona College, cites several reasons for the failure of these new plays, including uninspired writing, weak plots, and a concern for realism that clashed with the high stylization of the medium. He also criticizes some of the plays based on more recent historical events for taking too much license with the facts. While one could argue that the dramatizations of current events in Chikamatsu’s eighteenth-century plays were probably equally fictionalized, Jones is probably correct in intuiting that twentieth-century audiences were less willing to accept the slanted reality of the newer plays. Since the plays’ principal value had come most recently from their high-culture attributes, that is, their distance from contemporary reality, any effort to make the plays more current and realistic was self-defeating. In all probability, the new plays were simply not traditional enough for the aging connoisseurs and not modern enough for younger Japanese.

In the 1960s, however, perhaps in reaction to the American Occupation, a Nationalist sentiment reemerged, articulated most prominently by novelist and playwright Yukio Mishima (1925–1970). In order to recover what he saw as the lost “Japanese spirit,” Mishima advocated a return to the prewar imperial government and society.19 Traditional arts and culture once again gained prestige, probably as representative of this “Japanese spirit,” and traditional music (hōgaku) enjoyed a surge in popularity known as the hōgakki-boom. In this climate, bunraku seems to have provided an ennobling experience for patriotic Japanese, enabling them to see themselves as the heirs to a unique national treasure. Consequently, a bunraku stage was included into the new National Theater built in Tokyo in 1966. While the Shōchiku dispossessed the bunraku theater in 1962, the Chinami-kai and Mitsuwa-kai reunited the following year under the Bunraku Kyōkai. Buoyed by the tide of Nationalism and the economic growth of the 1970s, the theater recovered steadily. By the mid-1980s, the National Bunraku Theater had been built in Osaka, and Keene was able to write that the art form was “enjoying a prosperity that no one could have predicted even fifteen years ago.”20

Unfortunately, bunraku’s prosperity came to an abrupt halt with the stock market crash of 1989. The ensuing recession lasted well into the new millennium, and as incomes fell, bunraku became increasingly a distant extravagance. Thus, in the current climate of recovery, Hashimoto’s concern for fiscal responsibility seems at least understandable. He officially retired from politics at the end of 2015, after the citizens of Osaka rejected his Osaka Metropolis Plan, but whatever his legacy, Hashimoto was certainly correct to assert that “for people to truly appreciate a traditional art, they should be able to enjoy it.”21 He went on to say, “In a world with taboos, it’s difficult for people to express their honest opinions,” as if to suggest that people merely tolerated the theater, but were too polite to say it outright.

However, as the economy recovers, people are slowly returning to bunraku, and they do seem to be enjoying it. The bunraku attendance target for 2014 was actually exceeded, and even with the withdrawal of the subsidy in 2015, attendance remains high. Citizens’ groups, including the NPO Bunraku-za, have marshalled support for the bunraku, and both bunraku performers and administrators have found new purpose in promoting the theater more broadly.22 Even Hirofumi Yoshimura, the current mayor of Osaka, supports the theater, but because he lacks his predecessor’s flamboyance, his opinions have not captured the attention of the media.23

The theater is more visible than ever, with an active social media presence, prominent advertising, and community outreach. The route to the National Bunraku Theater from the Kintetsu-Nippombashi train station is clearly marked with colorful murals and signs along the underground “Namba Walk” shopping center. The lobby of the theater houses a small museum with displays of the tayū and shamisen player’s equipment, as well as a short history of the art form. In order to remove any barriers that might be created by the Edo period language, both supertitles and audio headsets are provided, with commentary in Japanese and English. The theater presents an annual Bunraku Appreciation Workshop, featuring informational programs intended to introduce bunraku to students, working people, and foreign tourists in May at the National Theater in Tokyo, and in Osaka in June.24 Furthermore, new, innovative plays are once again entering the repertoire, and they seem to be effectively recreating bunraku as a cultural treasure that is flexible, accessible, and willing to laugh at itself. One of these new plays, Kōki Mitani’s Sorenari shinjū (Much Ado about Love Suicides), not only pokes fun at Chikamatsu’s Sonezaki Shinjū, but changed the position of the musicians and required the puppets to swim. Since 2014, the National Bunraku Theater has also staged new plays written specifically for families with children.

As Keene observed in 1985, “The spell of Bunraku is irresistible to anyone who allows himself to be moved.”25 In spite of its many challenges, bunraku has endured, and if anything, Hashimoto’s criticisms have even benefited it somewhat, raising awareness and stimulating curiosity about the traditional art form. As essentially the same repertoire of plays has allowed audiences to see themselves variously as middle-class heroes, cultural sophisticates, and beneficiaries of a globally significant high art, so the future sustainability of bunraku will likely continue to depend on the strength of its contribution to the Japanese people’s sense of self. That is, bunraku will be successful only if, as Frith described, the music and drama allow its audience to see themselves differently and place themselves culturally. In reaching out to new and younger audiences, honoring tradition while making it accessible, and finding ways to be witty and innovative within the genre’s boundaries, bunraku seems to be finding the right formula. ■

NOTES

- Charles Weathers, “Reformer or Destroyer? Hashimoto Tōru and Populist Neoliberal Politics in Japan,” Social Science Japan Journal 17 no. 1 (2014): 86–87.

- Mainichi Japan, “Osaka Mayor Hashimoto Calls Classic Japanese Play ‘Unsatisfactory,’ July 27, 2012,” reprinted on Osaquoi, posted August 24, 2012, accessed March 13, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/y84mmr7p.

- William Andrews, “National Bunraku Theatre Parodies New ‘Terminator Genisys’ Movie Poster to Promote Traditional Japanese Puppet Theatre,” Tokyo Stages: Japanese Contemporary and Performing Arts, posted June 28, 2015, accessed March 13, 2018 https://tinyurl.com/y8nybsrh/.

- “Osaka Bunraku Theater Budget Cut.” The Japan Times, January 28, 2014, https:// tinyurl.com/y7rjbljb.

- Simon Frith, “Music and Identity,” in Questions of Cultural Identity, ed. Paul du Gay and Stuart Hall (Los Angeles: SAGE Books, 1996), 109; 124–125.

- Alison McQueen Tokita, “The Nature of Patterning in Japanese Narrative Music: Formulaic Musical Material in Heikyoku, Gidayū-bushi, and Kiyomoto-bushi.” Musicology Austrailia 23, no. 1 (2000), 105.

- Yoshinobu Inoura and Toshiro Kawatake, The Traditional Theater of Japan, (Warren Connecticut.: Floating World Editions, 2006), 161–162.

- Barbara C. Adachi, Backstage at Bunraku: A Behind-The-Scenes Look at Japan’s Traditional Puppet Theater (New York: Weatherhill, 1985), 15.

- Adachi, 5.

- Shizuo Gotō, “Bunraku: Puppet Theater,” in A History of Japanese Theater, ed. Jonah Salz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 173.

- Alison McQueen Tokita, Japanese Singers of Tales: Ten Centuries of Performed Narrative (New York: Routledge, 2017), 143.

- Stanleigh H. Jones, “Hamlet on the Japanese Puppet Stage,” The Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese 11, no. 1 (1976): 17.

- Samuel L. Leiter, “Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theater,” Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts no. 4, ed. Jon Woronoff, 2nd ed. (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, 2006), 413.

- Benito Ortolani, The Japanese Theater: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism, rev. ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 226–227.

- Adachi, 6.

- Luciana Galliano, Yōgaku: Japanese Music in the Twentieth Century, trans. Martin Mayes (Lanham, Md.: The Scarecrow Press, 2002), 129.

- Jones, “Hamlet,” 19–20.

- Jones, “Hamlet,” 33; see also Stanleigh H. Jones, “Experiment and Tradition: New Plays in the Bunraku Theater,” Monumenta Nipponica 36, no. 2 (1981): 118, 126.

- Steven Nuss, “Music from the Right: The Politics of Toshiro Mayuzumi’s Essay for String Orchestra,” in Locating East Asia in Western Art Music, ed. Yayoi Uno Everett and Frederick Lau (Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), 85–86.

- Adachi, x.

- Mainichi.

- Noriko Kameoka, “Bunraku: Recent Challenges & Developments,” in Theater Yearbook 2017: Theater in Japan, ed. Minoru Tanokura, trans. Alan Cummings, (Tokyo: Japanese Centre of International Theatre Institute. 2017), 152.

- Chiharu Sato (Chief Executive Officer, Osaka Arts Council), personal interview with the author, June 17, 2017.

- Kiyoshi Mizuochi, “Kabuki and Bunraku.” In Theater Yearbook 2017: Theater in Japan, ed. Minoru Tanokura, trans. James Ferner, (Tokyo: Japanese Centre of International Theatre Institute, 2017), 54–56.

- Adachi, ix.