Hiroshima, HIROSHIMA, “Hiroshima”

Many of us teach Hiroshima in passing, but few of us devote extended treatment to the topic. It is my thesis that more of us at all levels, but especially the seventh grade through college, should spend more time on Hiroshima, that the time we spend will repay both us and our students. It is my aim to introduce the recent scholarship (the latest 1985 and later) that is transforming our knowledge of Hiroshima and to suggest one way of teaching Hiroshima. Complete bibliographical references follow this essay.

Many of us teach Hiroshima in passing, but few of us devote extended treatment to the topic. It is my thesis that more of us at all levels, but especially the seventh grade through college, should spend more time on Hiroshima, that the time we spend will repay both us and our students. It is my aim to introduce the recent scholarship (the latest 1985 and later) that is transforming our knowledge of Hiroshima and to suggest one way of teaching Hiroshima. Complete bibliographical references follow this essay.

There are many facets of Hiroshima, and in our thinking and teaching, we will benefit by disentangling them. The Japanese language has at least four different ways to write Hiroshima: in Chinese characters 广岛. In the two different syllabaries (hiraganaひらがな and katakanaヒ口シマ), and in Latin letters. Depending on the writer, these four different Hiroshimas can carry differing impacts.1 I suggest that we make the same effort in English and write Hiroshima differently depending on which facet we have in mind.

Hiroshima

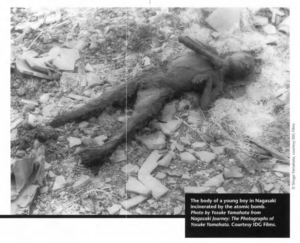

The first facet is the event on the ground: call it Hiroshima. What was it like to be in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945? As Fenrich has pointed out, most recently, American authorities clamped censorship on accounts of Hiroshima (Braw offers a fuller account of American print censorship, and Burchett reports his own experience as a reporter in Hiroshima immediately after the war) and on photographs. Thus, they suppressed photographs of the ground damage the bomb wrought. The great impact of Hersey’s Hiroshima (1946) is partly the result of the blackout. Seven full years passed before either Japanese or Americans were able to see photographs of Ground Zero. In Japan, the first photo essay appeared in the Asahi Gurafu on August 6, 1952 (its print run of over 500.000 sold out on the first day); in the U.S., Life Magazine published its first photo essay on September 29, 1952, Nagasaki Journey presents the censored stills of photographer Yamahata Yosuke. It is a stunning book and essays and interviews supplement the photographs. The surviving documentary film footage surfaced only in the late 1960s and almost by chance: Hiroshima-Nagosaki: August 1945, an I6-minute documentary available both in film and in the video, remains today the single most powerful footage of the bombs. Barnouw gives an account of the making of that film. As a general reference, the massive tome Hiroshima and Nagasaki is unsurpassed.

Also, slow in becoming available were translations of the key survivor accounts. Hachiya Michihiko’s Hiroshima Diary ( 1955; trans. Warner Wells, 1955) was the exception. Hara Tarniki’s Summer Flowers (1947-49: trans. Richard Minear. 1990), Ota Yoko’s City of Corpses ( 1948: trans. Minear. 1990), Toge Sankichi’s Poems of the Atomic Bomb ( 1951; trans. Rob Jackaman, Dennis Logan, and T. Shioda, 1977. and Minear, 1990), and Kurihara Sadako’s Black Eggs ( 1946; trans. Minear, 1994) were the rule. Beyond survivor accounts are works that take Hiroshima and Nagasaki as their theme: novels (lbuse, Oda): short stories (Atomic Aftermath, The Atomic Bomb), and plays (Goodman). In prose far too dense for students, Treat analyzes this literature.

Today there is no longer any excuse for us or for our students not to know what it was like to be atom bombed. There are also ready resonances across the curriculum, most notably to the survivor accounts and literature of the Nazi holocaust. See, for example. Kurihara’s essay compare Nazi holocaust writer Primo Levi and Hara Tamiki, Charlotte Delbo and Ota Yoko.2

HIROSHIMA

A second facet of August 6 is the Pacific War. Call this Hiroshima, HIROSHIMA. To this facet belong the events of the thirties in Asia, the Manhattan Project, Pead Harbor, and the war itself. What was the role of the bomb in ending the war? What roles did the U.S.S.R. and other non-Japan factors play in the decision to drop the bomb? What- if any- was the role of the bomb in ending the war? What did American policymakers know? When did they know it? Walker’s historiographical essay is particularly useful here. Bundy offers a revised inside look.3 Sherry is of major importance. in part for his concept of “technological fanaticism.” There are new biographies of American scientist-bureaucrat James Conant and German nuclear physicist Werner Heisenberg; the latter suggests that Heisenberg slowed down the German development of the atomic bomb for moral reasons, an interpretation which by inference raises the question of whether American scientists should also have had moral scruples. Goldberg has written a major biography of Leslie Groves. Lindee offers a fascinating analysis of the politics of science. In this case, the science of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC). She assumes that “a neutral zone [for science] does not exist, for anyone, at any time” (p. x) and writes of “science as both the creator and destroyer of truth” (p. 256) and of the ABCC as “colonial science” (p. 20). Rain of Ruin has over 400 photos in all, but only 15 of injuries to humans, fewer photos than the volume holds of the crews of Enola Gay and Bock’s Car: texts and captions arc sometimes inaccurate and inadequate.

Thirty years after its initial appearance, Alperovitz revisited Atomic Diplomacy in The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. This massive volume is clearly the publishing event of the fiftieth anniversary; all future work on the decision to drop the bomb will have to measure itself against The Decision. Alperovitz focuses (p. xiii) on “whether it was understood before the atomic bomb was used that the war with Japan could be ended by other means without significant loss of life.” Particularly useful is Book II., which traces the “architecture of an American myth; in the words of Ronnie Dugger (Boston Globe, August 6, 1995), “the true atomic bomb ‘ revisionist historians were not Alperovitz …or those who agreed with him but President Truman and his Secretary of State James Byrnes and Secretary of War Henry Stimson.” Bernstein has written an important series of essays. one of them (1993) on precisely this topic. Takaki’s slim volume covers much ground but adds little.

Pape argues that the keys to Japan’s surrender were, first, its vulnerability to the blockade and, second, the Soviet attack – not the bombing of civilians (conventional firebombing or the atomic bombs). Drea devotes his final chapter to ULTRA’s estimates of the forces defending Kyushu; the estimates increase to 600,000 (although Drea also quotes a Japanese source for the “in fact” figure of “approximately 900,000 soldiers” [p. 222 ] and two novelists for estimated U.S. casualty figures [71,000 for 48 days, 210,000 for 75 days; p. 218]). As those figures increase, so does the rationale for the atomic bombs rather than invasion (although invasion was never the only alternative).

Skates, whose subtitle is Alternative to the Bomb, offers a closer look; he states that after the surrender, U. S. forces “counted 216,627 troops – in southern Kyushu -” (p. 244) before concluding (p. 257): “Military and political leaders . . . did not see the bomb as a discrete and cataclysmic weapon. Instead, the bomb was another powerful component in a crescendo of force, including a Soviet declaration of war, imminent invasion, and the inevitability of destruction and strangulation through bombing and blockade.” Sigal breaks new ground. As here (p. 145 ): “Neither conciliation nor ultimatum, the Potsdam Declaration was no more than propaganda.”

It is no longer possible to argue that ending the war with Japan was the only reason the U.S. dropped the bomb. It is no longer possible to ignore the significant role of other factors: attitudes toward the U.S.S.R., bureaucratic inertia, and the desire to demonstrate (for a variety of purposes) the new weapon. It is no longer possible to ignore the fact that the early accounts were deliberately misleading. Zinn (p. 2) comments scathingly on the continuing American penchant for arguing whether the bombings were right (how often, even today. do we assign our students this paper topic?): “That this is arguable is a devastating commentary on our moral culture.”4

It is not the case that all scholars sing the same tune (for example, Alperovitz and Bernstein- whose interpretations are not so far apart- have carried on a continuing and mutually respectful debate) or respond as I do to Zinn. More than 20 years after being first indicted by “new left” historians for incompetent scholarship, Maddox cites the Drea figures (but not the Skates figure) in his argument in favor of both bombings. In Weapons for Victory (p. 154), he asserts that “Truman approved using the bombs for the reason he said he did: to end a bloody war that would have become far bloodier had an invasion proved necessary.” Maddox is a practitioner of the rhetoric of invective-Alperovitz, Bernstein, and the rest are either “incompetent” or “promot[ing] their own agendas” (p. 4). Those looking for an impassioned brief clearing Truman of all imputation of wrong will find it in Newman. Like Maddox, he attempts to justify both atomic bombs, as in the case of Maddox. The stridency of his rhetoric (“Truman bashers,” “Hiroshima cultists’ fanaticism.” and the like) is a giveaway that his evidence is much less convincing than he wishes. Maddox and Newman are the sole scholars I know of to join the attack on the Smithsonian’s Enola Gay exhibit. Pulitzer Prize notwithstanding., McCullough is neither original nor reliable. And there are still voices arguing that Japanese behavior prior to August 6 is the overriding context for HIROSHIMA.5

Maddox and Newman and McCullough are worlds apart from the newer scholarship. Alperovitz”s book led Sherry to suggest (in a review of Alperovitz, New York Times Book Review, July 30) this startling concept: ” … Ute use of the bomb allowed the U. S. to offer surrender terms it previously withheld, giving the bomb as decisive an impact in Washington as in Tokyo … American leaders bombed themselves into accepting Japan’s surrender terms.”

“Hiroshima”

A third facet of Hiroshima is the nuclear age. Call this Hiroshima “Hiroshima.” In this facet, the atomic cenotaph in Hiroshima’s Peace Park becomes. In the title of one of Kurihara’s poems. ‘The door to the future: “‘Hiroshima'” opens out into the nuclear age in world politics: consult, for example, Bundy and the pastoral letter of the Catholic bishop (Murnion). Lawyer (and former Secretary of the Interior) Stewart Udall reports on his investigations on behalf of the Americans unfortunate enough to live downwind of the test site in the continental U.S.; the book is somewhat less than authoritative. But it offers a fine point of entry for students. Gallagher offers portraits of the downwinders. The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb presents a fascinating sidelight: the Bikini Lagoon as an attraction for SCUBA-diving tourists.

Whether or not the atomic bomb played a significant role in ending the Pacific War, It marked the beginning of the nuclear age. The initial title of the now-aborted Enola Gay exhibit at the Smithsonian was “‘The Crossroads: The End of World War II. the Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War.” It is no coincidence that the last pan of that title- the Origins of the Cold War- was an early casualty of the assault of the Air Force Association and Congress, led by Nancy Kassebaum and Newt Gingrich.7

The media attention on the Smithsonian has obscured the more optimistic lessons we can draw from the simultaneous and near-instant withdrawal of the Postal Service’s proposed atomic bomb stamp. Maddox (p. 1) refers to the stamp as “gruesome.”‘ but of course, it was hardly gruesome; it perpetuated the antiseptic view from 30,000 feet. Moreover, in the context of the Postal Service series on World War II, it made eminent sense. Surely the mushroom cloud-obscuring Hiroshima though it does, is one of the dominant icons of the twentieth century.

Courtesy of IDG Films.

Hiroshima

A fourth facet is Hiroshima in our imaginations. Call this Hiroshima Hiroshima, perhaps the most important Hiroshima of all. Boyer, Franklin, and Wean are important sources here. So also are the works of a vast range of writers, poets, and artists: Sylvia Plath and Primo Levi, Kurihara Sadako, Galway Kinnell, George Grosz, and the Marukis. Atomic Ghost is one of several recent anthologies of the poetry of the nuclear age; The Nightmare Considered is a collection of essays on nuclear war literature. Lifton and Mitchell have chosen an apt subtitle: Fifty Years of Denial Minear ( 1995) explores the contrasting public awareness of the atomic holocaust and the Nazi holocaust. The Marukis work is available in Dower and Junkerman, and in the fine film “Hellfire: A Journey from Hiroshima,” Maruki Toshi’s children’s book is available in English.

One fascinating subtext of Hiroshima is its use as a codeword, excuse Pease treats Hiroshima as “the cold war’s transcendental signifier,” “a purely symbolic referent for a merely possible event- [that was reassigned the duty to predict an anachronistic event the what ‘will have happened had not the United States already mobilized the powers of nuclear deterrence against the Soviets.” Pease’s language is difficult, but his point is an important one: within days of August 6, Hiroshima became what someone else could do to us, and in the process, many Americans lost sight of the fundamental fact that we had done it already, not once but twice, to someone else.

A second subtext of Hiroshima is its role in the American master narrative. Here is perhaps the central reason for the political pressure that led the Smithsonian to cancel its exhibit; here is perhaps the single most important reason for us to spend classroom time on the subject. How do we reconcile the incineration of several hundred thousand civilians with our wishful image of our country as benign? What Sherwin wrote in 1981 (p. 350) holds true today: “In its current phase, the debate over Hiroshima and Nagasaki has little to do with how others see us: it has become strictly a matter of how we see ourselves.” Here is Engelhardt (p. 6): “The atomic bomb … also blasted openings into a netherworld of consciousness where victory and defeat, enemy and self, threatened to merge. Shadowed by the bomb, victory became conceivable only under the most limited of conditions, and an enemy too diffuse to be comfortably located beyond national borders had to be confronted in an un-American spirit of doubt.” As the poet Hermann Hagedorn wrote in 1946, the atomic bomb fell on America. The 50-year attempt to insulate the United States and its master narrative against a serious coming to terms with Hiroshima has unraveled; the abject surrender of the Smithsonian cannot hold off permanently the forces of change. Still, Engelhardt is overly optimistic in writing about the end of the American master narrative.

Hiroshima, HIROSHIMA, “Hiroshima,” Hiroshima. The event has many facets. Naming and labeling them with different labels will assist both us and our students to begin to grasp the immensity and the importance of the topic.

- Lisa Yoneyama, “Hiroshima Narratives and the Politics of Memory” (Ph.D. diss., Stanford, 1993), 41-42 suggests that the four Japanese transcriptions have these meanings: Chinese characters- the city before August 6, hiragana– hometown nostalgia, katakana, and Latin letters – the Hiroshima of August 6, and thereafter. But that analysis does not hold for the writers and poets I have translated, nor does it apply to Oē Kenzaburo, winner of the 1994 Nobel Prize, whose book of essays Hiroshima Notes uses katakana in its title (for both the place name and the word no-to) and Chinese characters in its text.

- But see also David G. Goodman and Masanori Miyazawa, Jews in the Japanese Mind: The History and Uses of a Cultural Stereotype, 172-179 (New York: Free Press, 1995) for problematic aspects of such comparisons.

- Barton Bernstein, “Seizing the Contested Terrain of Early Nuclear History; Stimson, Conant, and Their Allies Explain the Decision to Use the Bomb,” Diplomatic History, 17.1 (Winter 1993) establishes that Bundy was the shadow author 0f Henry L. Stimson’s “The Decision to Use the Bomb,” Harper’s, (February 1947), so Bundy has played a major role – covert and overt – in the atomic debate for almost 50 years.

- Don Bakker. Ed., Ending the War Against Japan: Science, Morality, and the Atomic Bomb (Providence: Brown University, 1995), a unit for high-school use, demonstrates just how difficult it is to present Hiroshima to students. It offers no photograph of human damage (there are three paragraphs, of few text and two drawings). No evidence of why Japan surrendered, few quotations from the Japanese of any kind, and none from American moralists. The issue is the decision; the setting includes prominence for the Potsdam Proclamation (Sigal to the contrary notwithstanding), and the three options for discussion are: 1. negotiate by offering to retain the emperor (“A Time for Peace”): 2. demonstrate the bomb (“Taking Responsibility for a New Era”); and 3. drop the bomb (“Push Ahead to Final Victory”). A demonstration was not a real issue for American decision-makers; there is little evidence that the decision was “difficult” (p. 1), let alone that it involved “wrenching moral questions” (p. 20). The text even asks (p.57): “If the Japanese had not surrendered on August 14, should the United States have dropped a third atomic bomb?” And an emphasis on values and on democracy and the inclusion of inflated casualty estimates for an invasion (p. 11), not to mention a section on “total war” in the ancient world-all; this sets the stage for a debate comfortably within the confines, of the American master-narrative. Perhaps most troubling of all is that the choice is choices– discrete, clearcut, unambiguous, whereas the events are so confused and muddy that choice points and choices are difficult to isolate. It is better by far to offer students choices rather than an unequivocal textbook, but choices carry their own baggage. Of Hiroshima (our facet 1), there are three paragraphs and two drawings: of “Hiroshima.” a whole lot: of HIROSHIMA, and of Hiroshima, little. The list of recommended readings (14 items) includes no book I have treated in this essay. Finally, I wonder if there is a pattern in the series as a whole compared to the patterns kids learn to deal with on multiple-choice tests designed by inexpert instructors- when in doubt, choose a number in the middle.

- For example, Robert P. Newman Truman and the Hiroshima Cult (East Lansing: Michigan State University, 1995) devotes most of a chapter to Japanese atrocities. In the year of the fiftieth anniversary, reputable publishers issued a number of books that do not withstand even cursory scrutiny. Notable here is Bruce Lee’s “Marching Orders: The Untold Story of WWII” (New York: Crown, 1995) and Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar’s “Codename Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan and Why Truman Dropped the Bomb” (New York.: Simon & Schuster, 1995 ). The former quote summarizes and paraphrases years of MAGIC intercept – virtually without analysis to argue (in the present tense throughout) that the MAGIC summaries “convince judge and jury in Washington to take extreme but necessary measures to destroy the Japanese government”‘ (p. 458), that they are “the fateful documents that condemn the Japanese people to a nuclear attack (p. 494). Lee concludes (p. 554) with a comment about Japans still powerful right-wing militarists” and ends the book with this sentence: “At times it makes one wish that America had never revealed its greatest secret of World War II: Magic.- Allen and Polmar descend to similar depths, representing (pp. 284-1851) a Unit 731 order to execute all Unit 731 victims as an order to kill all Allied POWs in August 1945 seems somehow to have escaped notice.

- Philip Nubile. Ed., Judgement at the Smithsonian: The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (New York: Marlowe, 1995) includes the text of the original exhibit. On the exhibit. See also Philip Nobile. ed., “The Struggle for History: Defining the Hiroshima Narrative,” Judgment at the Smithsonian, (New York: Marlowe. 1995). 129-156: Mike Wallace, “The Battle of 1he Enola Gay,” (Radical Historians Newsletter 72, May 1995), 1-12: a forthcoming special issue of Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars and a forthcoming book by Edward T. Linenthal. For the continuing campaign against the Smithsonian and “revisionism,” see John T. Correll’s “Washington Watch” column in Air Force Magazine (e.g., columns of November 1994 and September 1995 ). For a discussion of the press in the Enola Gay debate, see Tony Cappacio and Uday Mohan, “Missing the Target:· American Journalism Review (July-August 1995): 18-26.

- Kassebaum submitted the resolution that passed the Senate unanimously. Gingrich spoke of .. the enormous underlying pressure of the elite intelligentsia to be anti-American, to despise American culture, to rewrite history, and to espouse a set of values which are essentially destructive.”‘ and in a speech to the National Governor’s Association. The Enola Gay fight was a fight, in effect, over the reassertion by most Americans that they’re sick and tired of being told by some cultural elite that they ought to be ashamed of their country-” Clearly, the real issue is the history of the atomic bombing than the American self-image.