After more than a decade in the making, a groundbreaking ceremony took place for a grand classical Chinese garden in Washington, DC, in October 2016. The US $100 million project, expected to be completed by the end of this decade, will transform a twelve-acre site at the National Arboretum into the biggest overseas Chinese garden to date. Interestingly, the report allures that the garden project is meant to implant “a bold presence” of China near the US Capitol and “achieve for Sino-US relations what the gift of the Tidal Basin’s cherry trees has done for Japanese-American links.”1 It is clear that such overseas Chinese gardens, in addition to showcasing Chinese artistic and cultural expressions, also reflect the particular social-historical circumstances under which they were constructed. This article introduces the three most significant Chinese gardens in the United States—the Astor Court at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (1980), Lan Su Garden (Garden of Awakening Orchids) in Portland, Oregon (2000), and Liu Fang Yuan (Garden of Flowing Fragrance) at California’s Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens (2008). Occupying spaces varying from an indoor museum courtyard to a city block in the heart of downtown to a vast open space amidst the serenity of the San Gabriel Mountains, these three gardens vary in scale and style, as well as the social dynamics they embody. Together, they also provide an important opportunity to consider the newest classical Chinese garden in the nation’s capital.

The Astor Court

Located in the north wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Astor Court is the smallest yet arguably the most exquisite Chinese garden in the US. The garden project was initiated for practical purposes. In 1976, the Met purchased a set of Ming dynasty (1368–1644) furniture and contemplated a proper “Chinese” place to exhibit the new collection. This idea of building a garden court was enthusiastically endorsed by Mrs. Brooke Astor (1902–2007), a Metropolitan trustee and Astor Foundation chairperson, who spent part of her childhood in Beijing due to her father’s naval posting. Thus, the genesis of the Astor Court project stems from the convergence of an institutional maneuvering and a sense of personal nostalgia.2 The project was delegated to two Chinese architectural expert teams—the Nanjing Engineering Institute and the Suzhou Garden Administration, with the latter winning the bid.3 Soon, a full-size prototype of the Astor Court was built and examined by the museum’s administrative team.4 Following plan approval, materials for the Astor Court were collected, prepared, numbered in China, and eventually shipped to New York at the end of 1979 for installation. A total of twenty-six artisans (along with a chef) traveled to New York to execute their traditional craftsmanship, and the Astor Court was opened to the public in June 1980.

The current Astor Court occupies a rectangular 400-square-meter space on the museum’s second floor. Its layout, as stated in all its major press materials, is modeled after the Late Spring Studio in Suzhou’s Moon door entrance to the Astor Court garden in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. As visitors walk through a moon gate (symbolizing heaven and unity, while also making the act of entering ceremonious), a zigzag-covered corridor running along the wall takes visitors to “another world.” The winding corridor extends the distance that visitors would walk (compared to a straight path), and the zigzag path constantly offers different viewing points. The stone steps take visitors to an open courtyard, surrounded by lattice windows, a monolith, a small rockery mountain with a spring pond, a half-pavilion, and a three-bay main hall where the Ming furniture pieces are displayed. Though small, the Astor Court skillfully includes and artistically displays the four key elements of a classical Chinese garden: rock, water, plants, and architecture (whose employment is elaborated below).5

As the first Chinese garden constructed in America, the Astor Court project occurred at a pivotal historical time. Following President Richard Nixon’s ice-breaking visit to China in 1972, the US and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) established official diplomatic relations in 1979. Coinciding with the normalization of the China-US relationship, this overseas garden project was bestowed with tremendous social-political significance.

The great lengths to which the authentic materials were incorporated into the Astor Court remain unparalleled. The most precious materials include the nan wood used in the construction of fifty hand-hewn columns. The nan tree is a broad-leafed evergreen indigenous to China whose warm radish color and insect and moisture-resistance make it ideal for use as furniture and architecture. However, excessive harvestation pushed nan trees to the edge of extinction during the late Qing time. To prepare materials for the Astor Court, a special team of loggers was dispatched to harvest nan wood from the valleys of Sichuan province. In addition, the Chinese government reopened the Lumu Imperial Kiln (outside of Suzhou, which had been closed by the end of the Qing dynasty) to produce the roof tiles and floor bricks. To commemorate this reopening of the kiln, each terracotta tile was stamped with a seal stating, “Newly made in the Suzhou Lumu Imperial Kiln in 1978.”6

However, a garden’s authenticity always reflects a constant negotiation between the “sacred” tradition and reality. For the Astor Court, the biggest challenge was the weight-bearing capability of the second-floor space. In fact, the initial Nanjing Engineering Institute design was forfeited because its planned use of water and rocks exceeded the building’s safety limit.7 For the same reason, the walls of the Astor Court were constructed of wire mesh with plaster rather than real bricks. Although the Astor Court has a skylight enabling visitors to stroll the garden court in natural daylight, it is, after all, inside an air-conditioned space with a constant temperature. Therefore, plants that need climatic change to thrive are absent, and potted flowers are brought in to represent the change of seasons.8

In addition to the museum’s official website, the Astor Court features abundant educational resources. Alfreda Murck and Wen Fong’s article “A Chinese Garden Court” (1980) provides detailed explanation and context on Chinese garden culture and its significance in Chinese intellectual history, as well as the Astor Court’s prototype, Wangshi Yuan. Gene Searchinger’s documentary film Ming Garden (1983) illustrates valuable footage of the garden’s construction. Moreover, the museum also features the booklet Nature within Walls: The Chinese Garden Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Intended primarily for teachers of grades five through twelve, this booklet includes a brief overview of both Chinese garden culture and the Astor Court garden, as well as suggested classroom discussion topics and relevant activities. The ten-minute narrated video tour accompanying the booklet enables students to virtually tour the space.

Lan Su Garden

Su Garden. Source: Photo by

Victoria Ditkovsky. © Shutterstock

Unlike the Astor Court, which only took a couple of years to materialize, Lan Su Garden underwent more than a decade of planning, fundraising, and building. In 1988, Portland and Suzhou become sister cities, and a year later, the proposal for the Portland Chinese Garden was officially unveiled. A major breakthrough occurred in 1995 with the donation (on a ninety- nine-year, US $1 lease) of a piece of property from Northwest Natural Gas Co. The garden’s name combines characters from the names of both Portland and Suzhou. “Lan” is a character from the Chinese translation of Portland (Bo te lan), and it is also the Chinese word for “orchid.” Similarly, “su” is a character in “Suzhou,” and also means “arise” or “awaken.” So the garden’s literary name, “The Portland Suzhou Garden,” can also be interpreted poetically as the “Garden of Awakening Orchids.”9

Today, the Lan Su Garden occupies a full city block in the heart of downtown Portland. Incidentally, this location is actually considered a preferred spot for Chinese gardens. As Ji Cheng (b. 1582), the author of The Craft of Gardens (ca. 1631, considered the world’s earliest extant treatises on garden design) states, if one “could find seclusion in a noisy place, there is no need to yearn for places far from where you live.”10 Most of the classical gardens in the Yangtze delta area are urban gardens that manage to create a sense of seclusion and spaciousness within urban hustle and bustle.

Lan Su Garden is a full-scale Suzhou-style garden approximately ten times the size of the Astor Court. Visitors traverse a south-facing stone gateway and a small open courtyard space before formally entering the garden. This design is a creative combination of poetics and practicality. Portland design guidelines require corner entrances. Therefore, this requirement prevents the garden’s main gate from being positioned directly on either street. Since this courtyard space is something too precious to lose in a 4,000-square-meter garden, the archway symbolically reclaims the space. The overhead inscription of the stone gateway reads, “All Nature’s Splendors Captured in This Gourd-Heaven.”11 Visitors can appreciate a precious and treasured piece of Lan Su Garden in this outer courtyard. It is a standalone Taihu rock named banyun (“half of a cloud”). Rocks are favored in Chinese gardens for multiple philosophical and aesthetical reasons. In Chinese garden culture, rocks are symbolic mountains. The Analects of Confucius includes the assertion “the wise delight in water, the humane delight in mountains,” while Daoists see the mountain as where the immortals dwell.12 In Chinese history, Emperor Wudi of the Han dynasty tried to lure immortals down by building rock mountains in his garden. Northern Song Emperor Huizong’s fetish with rocks almost financially crippled the empire. As writer and garden designer Maggie Keswick pointed out, the Chinese “worshipped” rocks with religious zeal.13 Taihu rocks are light gray limestones retrieved from Lake Tai (west of Suzhou) and are appreciated for their shou, tou, lou, and zhou characteristics. Shou (thin) describes the shape and orientation of the stone. A good piece should be slim and dynamically spiral. Tou (transparent) and lou (leak) refer to the holes and cavities. It is believed that for an excellent piece of Taihu rock, one should see the raindrops dripping in the holes when it rains and smoke rising out of the holes if burning incense in the bottom. Zhou (wrinkles) refers to the stone’s intaglio lines and grainy surfaces. As evident, a prized piece of Taihu stone embodies the yin-yang complementary opposites, such as bulky and slim, heavy and light, smooth and rugged. “Half of a cloud” demonstrates all these features, and the name itself invokes another dualism: the idea of lightness and airiness inherent in the stone’s name forms a complement to the heavy stone’s substance.

Lan Su Garden proper centers on Lake Zither. The combination of rock and water form the ultimate yin-yang duality in Chinese gardens. Banyun, a rare piece of Taihu rock standing in the outer courtyard of Lan Su Garden. Rock is usually yang (hard, bright); water is yin (soft, dark). However, from another perspective, water could also be yang, as it is always in motion and active, while rock is still and passive. In Chinese gardens, water and the midlake architecture can “divide and multiply” the water surface, thereby increasing the depth of the space. In Lan Su Garden, the zigzag path and the midlake pavilion (Moon-Locking Pavilion) add to the variety of routes through which the garden can be traversed and explored. The open-sided midlake pavilion also offers multiple viewing points of the lake.14

Plants are another significant feature and highlight of Chinese gardens. The most favored plants, such as orchids, plum blossoms, bamboo, pine, and chrysanthemums, are not only appreciated for their aesthetic beauty, but more importantly, for the ethical and moral values they invoke. Both orchids and bamboo are often compared to Confucian gentlemen. The perfume of orchids is subtle yet prevailing and undiminished by the absence of people to appreciate it, just like a perfect person’s virtue. The hollowness of bamboo stems are often read as indicators of humility and humbleness, while its bend-but-not-break feature symbolizes resilience. To complete the landscaping of the Lan Su Garden, fifty Oregon nurseries donated plants. The osmanthus tree is considered the star of the garden. The outstanding gnarled pine tree was rescued from destruction along a highway.15 Other than actual plants, Lan Su Garden also has a dedicated space, Celestial Hall of Permeating Fragrance, devoted to another favored plant in Chinese culture, the plum blossom. Blooming in harsh winter when most other flowers have already faded, the plum blossom symbolizes the quality of enduring hardship. The plum blossom trees in the courtyard, when combined with the pebble stone pattern of “blossom and cracked-ice.” and the couplets praising the symbolic meaning of the flower, bestow this scholar’s studio with an integrated theme.16

Like all the Chinese gardens in North America, Lan Su Garden features authentic materials and traditional tools and techniques employed in the garden’s creation. The frame of each pavilion is made with mortise and tenon (an ancient technique for affixing joints) rather than traditional screws and nails. Every piece of granite in the garden was previously handworked in China to fit into the foundation. Painstaking manual labor was involved in everything from paving the pebble stone path to crafting the handmade leak windows. However, a variety of creative methods and contemporary modifications underlie these authentic finishes. As an outdoor garden in Portland, the biggest issues that Lan Su Garden needed to resolve involved meeting city building codes for seismicity and coping with Portland’s relatively harsh winters (compared to those in southern China). Consequently, carbon cores are inserted in each of the pillars and beams to enhance their support capability. The interior posts of the two-story teahouse were made of concrete with an underlying structure reinforced with rebar. Roof tiles provided another challenge. Traditional Chinese rooftop clay tiles are usually overlaid on the roof and hence highly vulnerable in the case of an earthquake. In the Lan Su Garden, copper wire was attached to every fifth roof tile, and the end tiles were mortared into the structure. Another American-specific modification was designed to meet requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which mandates wheelchair accessibility on a paved surface. Therefore, visitors to Lan Su Garden will find some steps are replaced with ramps, while the traditional door thresholds (for the proper Chinese etiquette of entering) were made removable. Interestingly, not all “authenticity” was compromised or forfeited. For instance, safety code requires the balustrade guardrails surrounding the midlake walkway to be of certain heights. Yet the city eventually made an exception for the garden in the case of the walkway guardrail.

Like the Astor Court, the Lan Su Garden’s construction is also recorded in a documentary (Raymond Olson’s The Creation of Portland’s Classical Chinese Garden, 2010).17 Charles Wu’s Listen to the Fragrance offers detailed explanations on the various literary inscriptions and couplets found in the garden. In addition, Lan Su Garden features a most creative visitor guide brochure featuring a die-cut window on the front page. The unique brochure constantly reminds visitors to hold the copy and view the scenery through the window cut while touring the garden. This ingenious design of “framed view” instantly transforms natural scenery into painting-like

landscapes and again speaks volumes about traditional Chinese aesthetic ideas that value “cultured” views over pure natural vistas.

Liu Fang Yuan

Liu Fang Yuan. Photo by author.

Located in San Marino, California, at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, Liu Fang Yuan is a 3.5-acre space that includes plans to extend to twelve acres when the second phase is completed. Similar to the Astor Court, the Liu Fang Yuan project burgeoned from a philanthropist’s goodwill. In 1999, Huntington Library board member Peter Paanakker bequeathed a US $10 million gift to construct a Chinese garden when he passed away. However, over a ten-year fundraising and building period, the project expanded well beyond a single person’s will to feature the collective efforts of Chinese-Americans in the United States and abroad. Donors interviewed in Liu Fang Yuan’s press materials, such as those featured in the documentary film Coming Together: Creating the Chinese Garden at the Huntington (2009, Bronze Winner Telly Awards), all regarded participating in the project their obligation to maintain Chinese traditions and contribute to their local community. In other words, each conveyed a connection to their heritage while acknowledging and embracing their new identity. Administrators of Liu Fang Yuan made special efforts to acknowledge these different forms of contributions throughout the garden.

website at https://tinyurl.com/yao73ksj.

Built in mountainous southern California, Liu Fang Yuan practices what Ji Cheng regards as the highest techniques of garden design, i.e., to “follow” the existing land contour and “borrow views” from the extant landscape. For instance, to create the Lake of Reflected Fragrance, designers took advantage of a low point in the planned site that collects water runoff from the surrounding higher land. The US engineering team used a biofiltration skimmer system that sends lake water through a network of perforated pipes buried under gravel. Like Lan Su Garden, the water circulation system is intentionally calibrated for a level of organic murkiness.

Given its size, Liu Fang Yuan features more pieces of architecture than other overseas Chinese gardens. Naming architecture and natural scenic spots in a Chinese garden is like “dotting the dragon’s eyes.” It is quite common for the favored “names” in Chinese gardens to be rich in literary association. For example, the Bridge of the Joy of Fish refers to a famous anecdote in the Daoist classic Zhuangzi, where the Daoist master Zhuangzi and his friend Hui Shi debate over how (and whether it is possible) to know if the fish are happy or not.18 Liu Fang Yuan’s name itself is also highly poetic and allusive. “Liu Fang” (“flowing fragrance”) refers to the scent of flowers and trees, as well as the name of the famous Ming era painter Li Liufang (1575–1629), known for his refined landscapes.19

Thanks to the precedents established by other classical Chinese gardens in the US, efforts to ensure authenticity and modification became standard by the time of Liu Fang Yuan’s construction. Indigenous materials such as the Taihu rocks, roof tiles, wood columns, paving stones, and granite were all imported from China, and skilled craftsmen were invited. Like Lan Su Garden, Liu Fang Yuan also needs to meet state seismic codes. Therefore, steel rods were wrapped in wood and thus “hidden” above or below the visible wood framing to provide structural support. Door thresholds were made removable and roof tiles interwoven with copper wire. The height of the granite banisters and the width of the gaps between bridge railings were also adjusted to meet safety requirements. These innovative design and construction methods preserve the look, texture, and feel of the traditional materials and techniques.20 Such details about the Liu Fang Yuan project, as well as scholarly insights on how to appreciate Chinese gardens in general, can be found in the monograph

Conclusion

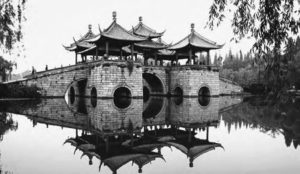

It is generally acknowledged that private Chinese classical gardens have two traditions: the Suzhou tradition and the Yangzhou tradition. While the former reflected heritage of Ming-Qing era scholar-officials, the latter were mostly created to be the estates of wealthy merchants. Up to this point, most of the classical Chinese gardens in the US are proud to be authentic Suzhou-style gardens. It is in this sense where the new garden at the National Arboretum, National China Garden, is all the more unique. The new garden in the nation’s capital seeks to recreate a Yangzhou-style garden—Ge Garden. In addition, the other signature cultural spots around the Slender West Lake in Yangzhou, such as the White Pagoda and the The Five-Pavilion Bridge at Yangzhou’s Slender West Lake. This bridge will be recreated at the new National China Garden in Washington, DC.21</sup The establishment of this new garden will add one more dimension to the presence of “Chinese-ness” in the US.

NOTES

1. Adrian Higgins, “China Wants a Bold Presence in Washington—So It’s Building a $100 Million Garden,” The Washington Post, April 27, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/yc7sxsaq.

2. Han Li, “From the Astor Court to Liu Fang Yuan: Exhibiting ‘Chinese-ness’ in America,” Journal of Curatorial Studies 4 (2015): 287–288.

3. See Zhang Weiren, “Suzhou yuanlin shoudu ‘chukou’ zhuiyi” (“Recollection on the First ‘Export’ of Suzhou Garden”), Modern Suzhou 10 (2008): 16–19, for an insider story of the project bidding from the Chinese side.

4. This sample court is still standing in Suzhou as a public park.

5. The narrative that the Astor Court is a replica of this famous studio grants an aura of authenticity for the court. Yet, interestingly, Zhang Weiren—one of the three major designers for the project—reveals in his memoir that they did not intend to reproduce the Late Spring Studio. However, given the size and shape of the assigned space in the Met, the current blueprint of the Astor Court is probably the only design that

could incorporate all the crucial garden features. Zhang, 19.

6. Alfreda Murck and Wen Fong, “A Chinese Garden Court: The Astor Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 38, no. 3 (1980): 60–63.

7. Zhang, 18.

8. Murck and Fong, 62.

9. When first opened to the public in September 2000, the Lan Su Garden was known as the Portland Classical Chinese Garden. The name was changed to Lan Su Garden at its ten-year anniversary celebration.

10. Ji Cheng, The Craft of Gardens, trans. Alison Hardie (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 47.

11. This alludes to the Daoist idea of “gourd-heaven,” often used as a symbol for a classical Chinese garden, implying a microcosm of all nature’s wonders in a limited space. Charles Wu, Listen to the Fragrance (Portland: Portland Classical Chinese Garden, 2006), 41.

12. The Analects of Confucius, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 45.

13. Maggie Keswick, The Chinese Garden: History, Art, and Architecture (Cambridge:Harvard University Press, 2003), 169.

14. It is suspected Lake Zither might have been leaking ever since the garden’s opening, which eventually led to a $29,000 water bill in 2002. In 2004, the city filed a $1.03 million lawsuit against the garden’s architectural firm and the subcontractor that created the lining and bed for Lake Zither.

15. Raymond Olson, The Creation of Portland’s Classical Chinese Garden (Portland: Sacred Mountain Productions, 2010), DVD.

16. The inscription reads, “Braving the snow, myriad flowers come into blossom; leading the world, a single tree heralds the spring.”

17. Other than this documentary on the Lan Su Garden, Raymond Olson also produced Blending with Nature: Suzhou Classical Chinese Gardens (Portland: Sacred Mountain Productions, 2007), DVD, which provides excellent visual resources for teaching Suzhou gardens and Chinese garden culture.

18. Interestingly, “Knowing the (Joy of the) Fish” pavilion in Lan Su Garden refers to the same anecdote.

19. June Li, “Liu Fang Yuan, the Chinese Garden at the Huntington,” in Another World Lies Beyond: Creating Liu Fang Yuan, the Huntington’s Chinese Garden, ed. T. June Li (San Marino, California: The Huntington Library, 2009), 20.

20. Laurie Sowd, “The Making of Liu Fang Yuan: A Brief History,” in Another World Lies Beyond, 32–34.

21. Please visit the garden’s official website (http://nationalchinagarden.org/v/explore/) to explore the current plan of the garden.