Modern-day viewers can glimpse the maritime world of Edo period (1603–1867) Japan through the ubiquitous ukiyo-e, woodblock print. The majority of early woodblock prints were pictures of beautiful women often associated with the pleasure quarters and available for mass consumption. As printing techniques improved, artisans experimented with new perspectives, and subjects’ woodblock prints attained a higher status. Changes in society’s perception of actors, courtesans, and artists mirrored a shift in tastes as power transitioned from the court class to the samurai and gradually to townspeople. (note 1) Though courtesan and kabuki actor prints were still popular, for the first time, landscapes and daily life scenes became more prevalent. Landscape prints were popular with publishers since they were more profitable; unlike the ever-changing fashion world that required regularly updated prints, scenes of Mount Fuji or riverboats were constant and could be reprinted indefinitely for little cost.

As landscape prints’ popularity grew, artists delved into more scenes depicting less “noble” characters, showing townspeople and commoners in all manner of poses and actions. Travel images, scenes of everyday life, and meisho (名所; famous places)became important subjects of woodblock prints. Artists incorporating these images into their work increasingly commemorated shoreline scenes, fishing images, and travel by watercraft. Although the scenes were filtered through the artist’s eye and accuracy was sometimes sacrificed in favor of aesthetics, they still offer a look into aspects of daily life in early modern Japan that often went unrecorded in written documents. Information about how the environment in which they were used shaped the vessels’ construction, the types of people both working and playing onboard ships, and the tools associated with maritime endeavors can all be found in the following selection of woodblock prints.

Fishing Vessels

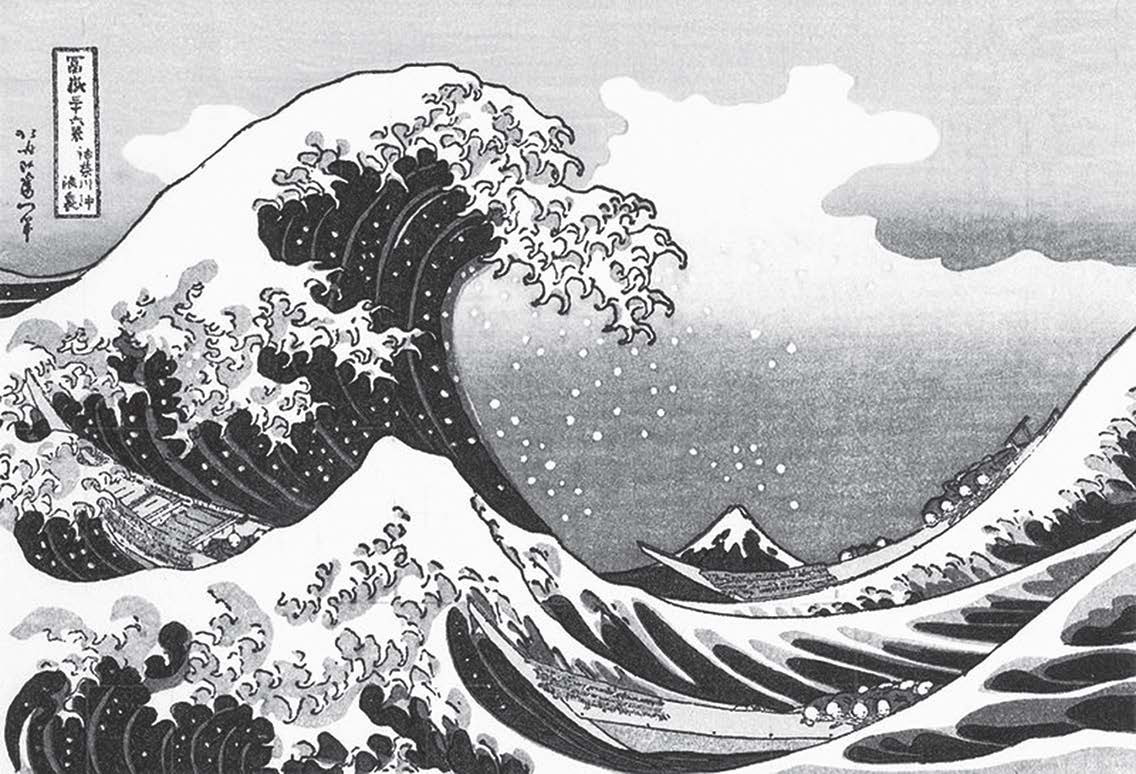

Katsushika Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa (Figure 1) is perhaps the woodblock print best known in the West and part of his Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series. Though the wave commands attention, three small fishing boats are also depicted. The upward-jutting stempost is characteristic of fishing vessels (kari-bune; 狩船) and fast boats used to transport a fresh catch to the market (oshiokuri-bune; 押送船). The view of the leftmost boat reveals a midship’s planked-over area, which was likely a storage container for the fish caught. The print also provides hints to seafaring practices, revealing the number of sailors typically manning such a vessel and the practice of draping reeds over the sides to function as wave breakers.

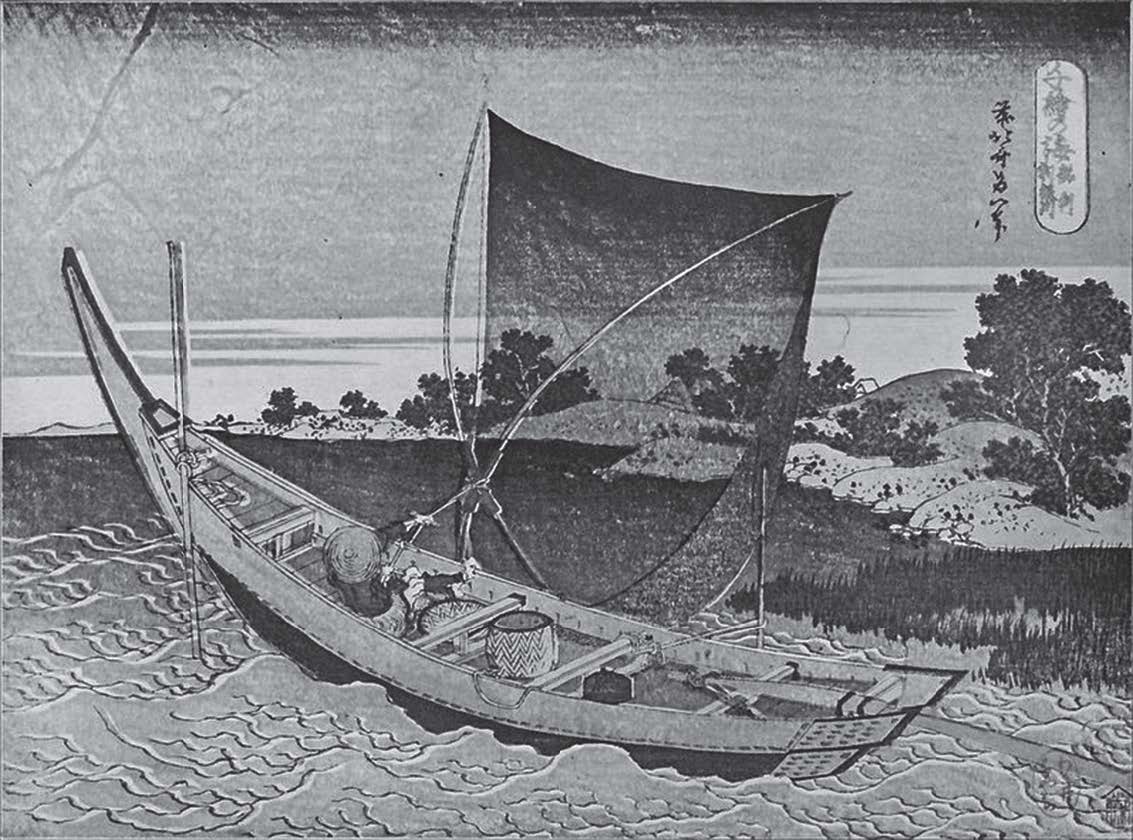

Tone River in Shimosa Province, (Figure 2) another Hokusai print, shows an entirely different type of fishing, depicting a single fisherman using a “four-armed net” (yotsude-ami; 四 手網). Unlike the previous image with many men far offshore, this print shows a smaller-scale fishing style nearer to the coast. Instead of a storage container built into the boat, the fisherman has a single basket to hold his catch. A sculling oar (ro; 櫓), is tied in the stern, indicating that the boat could easily be propelled by one person. Though the boat itself is shaped similarly to the vessels in the Great Wave print, much more construction detail is visible, showing planking patterns and deck beams. Regular marks along the interior and exterior of the boat denote the use of fasteners, ship’s nails that were covered with caps to protect the metal from direct exposure to saltwater.

Ferryboats

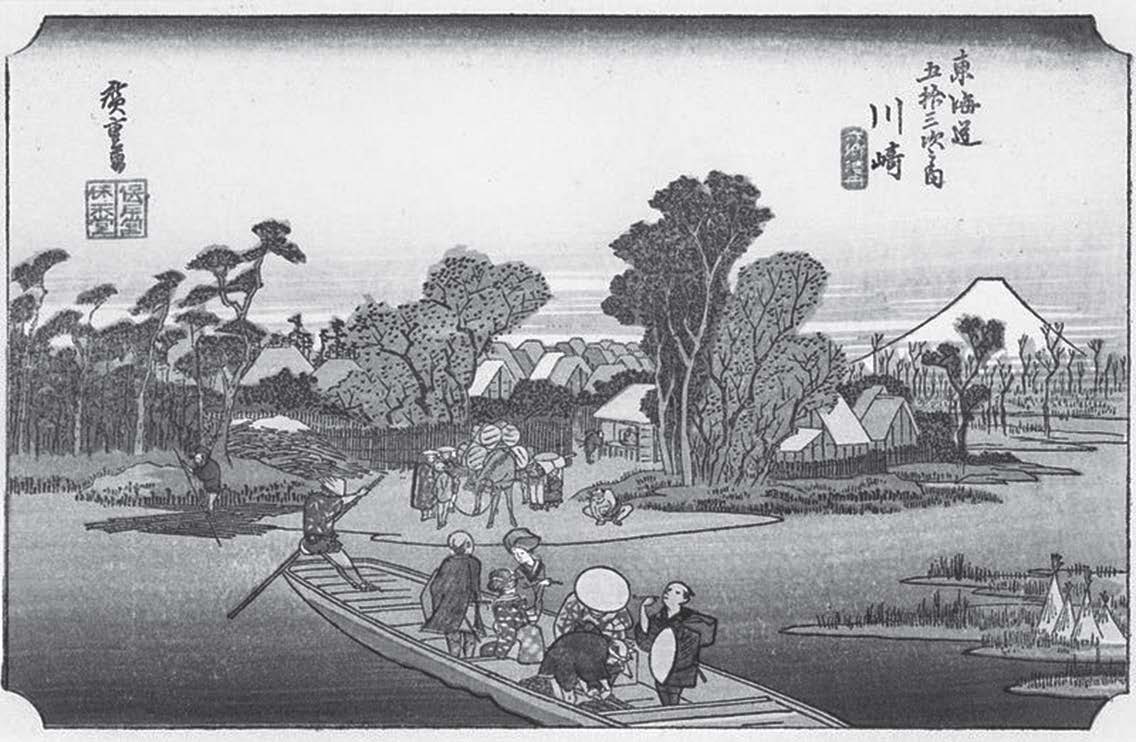

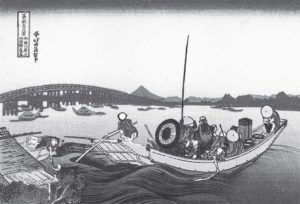

A number of prints depicted people traveling from place to place, crossing rivers and lakes in ferryboats. Andō Hiroshige’s Kawasaki (Figure 3), part of the Fifty-Three Stages of the Tōkaidō series, shows a ferry crossing the Rokugo River, and Hokusai’s Ferry Boat at Onmayagoshi (Figure 4) is located on the Sumida River. Both prints share some similarities that demonstrate important aspects of river travel. There were no piers or docks depicted at the ferry landings. Instead, these prints show the flat, wide stem and stern typical of many ferries, allowing the boat to be pulled up anywhere on shore for easy exit and entry. The prints give a sense of the range of the people who would make use of the ferries, from women with parasols to a welloff man smoking a pipe to a loincloth-wearing peasant waiting on shore next to a burdened horse. Other ferryboat images show horses crossing on the boats as well, indicating how critical these boats were for transport of people, animals, and things. Hiroshige’s ferryman uses a pole to propel the boat to shore, while Hokusai’s depiction again shows the sculling oar, suggesting that the Sumida River crossing was deeper than the Rokugo and poles alone would be insufficient.

Pleasure Boats

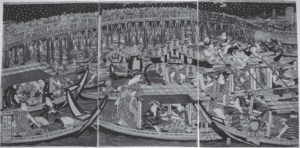

Few prints demonstrate the prominence of boats in Edo daily life as strikingly as the ones commemorating fireworks displays near the Ryōgoku Bridge with boats congregating nearby to allow people to enjoy the cool river breezes and the summer spectacle. Keisai Eisen (Figure 5) demonstrates the range of vessels used for pleasure. Many are a variant of roofed boats (yane-bune; 屋根船), sheltering the kimono-clad women and their escorts with bamboo blinds that could be lowered for more privacy later on in the evening. A large boat in the center of the print is festooned with lanterns likely proclaiming the name of the restaurant that catered the evening meal. A social hierarchy is visible in these prints between those out for pleasure and those who were at work,

with men holding poles atop the roof of the largest ship or stationed with sculling oars in the sterns of the smaller ship, propelling their passengers to the best vantage point along the river. Kitagawa Utamaro’s Night on the River (Figure 6) depicts a more intimate view of pleasure boating that also shows a social clash. A roofed boat filled with women and their escorts is drawn alongside a fisherman deploying a four-armed net. The elaborate hairdos and clothing of the people on the roofed boat suggest a pleasure outing. The women (and even some of the men) gawk at the fisherman, peering into his fish bucket and watching as his efforts lift up a fish from the waters. The

scene implies that the men and women on the pleasure boat would rarely encounter someone like the fisherman up close, but on the river waters, the two worlds are brought closer together.

Cargo Vessels

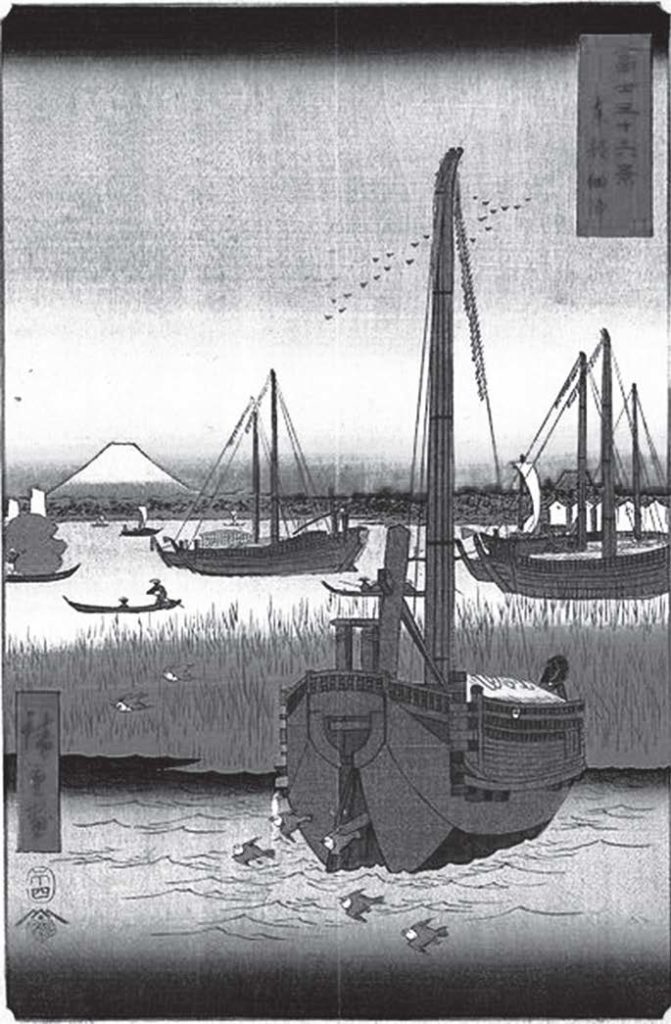

One of the boats most representative of the Edo period maritime world is a coastal trading vessel (bezai- sen; 弁財船). These large-masted merchant ships plied the east and west coasts of Japan, traveling from port to port to facilitate trade between far-off provinces. Hiroshige’s Off Tsukuda Island (Figure 7) from the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series is typical of the many prints depicting these ships. Tsukuda Island lay at the mouth of the Sumida River, and ships would unload cargo there to be transported by smaller boats farther inland. Indeed, this print shows the huge size of these ships compared to the fishing and ferry boats in the background. The upswept stern and high railings are representative of this type of vessel, capable of carrying hundreds of tons of cargo.

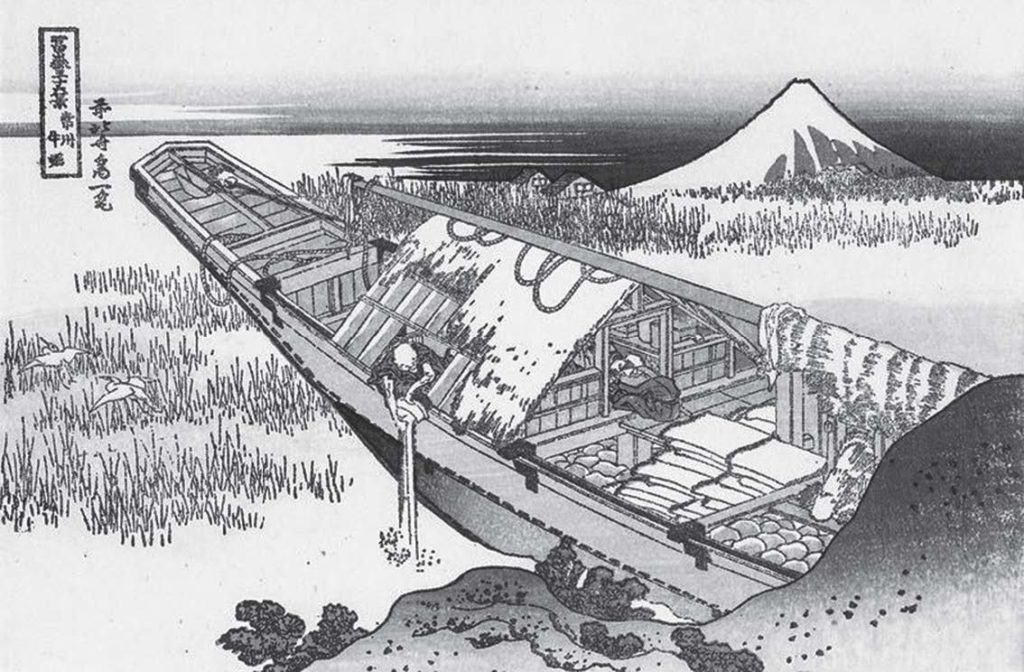

Hokusai’s View from a Boat at Ushibori (Figure 8) from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji depicts the other end of the cargo boat spectrum: the takase-bune (高瀬船), a riverboat most commonly found around the Tone River near Edo. These vessels often had provisions for living quarters aboard ship, hinted at in the deckhouse structure in this print. Also shown are the bolts of textiles and unidentified bundles of cargo in the hold, which may have been rice for annual taxes sent to the capital. A final detail of note in this print is the tool placed in the bow, known as an akakumi and used to bail bilgewater. Beginning shipwright apprentices working near the Tone River were given materials to make this tool if their mentors thought they showed promise in the trade.2 Depicting such a tool in this print not only indicates the simple need for it aboard ship, but also calls to mind the apprentices in that region and the traditions inherent in shipbuilding.

NOTES

1. Andrew C. Gerstle, 18th Century Japan: Culture and Society (Sydney, Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1989).

2. Junichi Saga, Memories of Wind and Waves: A Self-Portrait of Lakeside Japan (Tokyo: Kodansha Intanashonaru, 2002), 188.