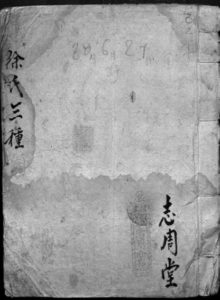

In September 2005, at the Panjiayuan Antiques Market in Beijing, I bought a book of materials once used by an elementary school teacher. It seems the teacher took some of his classroom materials to a shop in the city of Panshi in Jilin Province in northeast China and had them copied onto clean, handmade paper and bound together with string. The shop put its stamp on the cover, so we know the city where it was located.1 The title the shop wrote on the cover of this collection was Three Items for Mr. Xu (Xushi sanzhong), so I call the man discussed in this paper Teacher Xu.2 I picture him as a man, perhaps in his forties, who enjoyed being a teacher and was welcoming with his young students. I estimate the book was compiled about 1880.

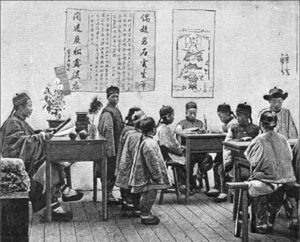

We know some things about elementary classrooms in the late Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), when this book was used. The typical classroom was a fairly small room, sparsely furnished. There was a desk or table for the teacher, and usually several smaller desks or tables for the students. The classroom would likely have a small case for books, where various educational texts would be stored. The paper used for the textbooks was soft and very pliable. Some texts had been printed from woodblocks; some were handwritten like the book examined here. Most classrooms probably had a low table where hot water was kept, perhaps along with tea and teacups for the refreshment of both teacher and students. In colder climates, a small coal stove was somewhere in the room, although both teacher and students were expected to dress warmly and take their lessons while bundled up.3 Classes were almost always small, consisting of probably three to ten students. They were almost always boys, ranging in age from about eight to older students of fifteen or sixteen. Schools were generally privately run by clan temples, wealthy families, or teachers who set themselves up to offer education. Tuition fees for the students could be provided by wealthy families or local business associations. Families who could afford to send their boys to school paid the tuition directly. There was no standard or approved curriculum, but customarily, a number of well-known classic books were usually studied.4

In China during the Qing Era, most people had no formal education or only a few years of elementary schooling. Most people could not read or write well, but it seems likely that most people knew some written characters.5 Many scholars believe that only 30 percent or less of the people were fully literate. Because few people had a more complete education, those who were fluent in reading and writing, and who knew in detail about China’s rich literary and intellectual culture, were highly respected. The teacher was an honored person and was often seen as an embodiment of Confucian teaching. Confucius was lauded as the xianshi (“first teacher”) because his emphasis on life-long learning, diligent study, and thoughtful discussion set the stage for how Chinese scholars, intellectuals, and students would approach education. A sense of Confucius and his teaching has always permeated schools and classrooms in China.

Yet in spite of this, the men who made their living by teaching were not paid very well. We have the short record of a teacher, probably in northeast China (Manchuria) in the 1920s, who wrote this about his monthly income: “School opened on May 19. From Huamin (School), I received 20 yuan dayang piao (foreign money) in guobi (national currency) and 4 jin (almost four kilograms/nine pounds) of millet. I purchased a shovel for 3 yuan, handed over 10 yuan for coal, then bought chalk, a broom, and took out a newspaper subscription for 2 yuan.”).6 We can see that he was paid in both cash and food, and that basic expenses took up much of his salary from this job. It appears he also had other teaching jobs in the area in order to make ends meet.

The first item copied in this elementary school textbook was the famous Thousand Character Classic (Qianziwen).7 The text uses four-character phrases that rhyme to introduce ideas about moral precepts, traditional values, and natural phenomenon. It may have been originally compiled in the 600s, and it has been taught in the classroom since then and is considered a basic primer for elementary education. Other similar texts were also used in classrooms.8

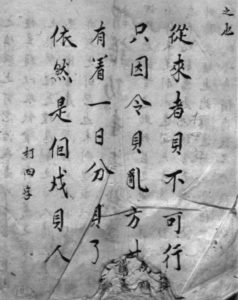

The second item for classroom use in Teacher Xu’s copied collection was a riddle (dasizi miyu).9 In this riddle, the boys were given some sentences to read. By picking two characters from each sentence and combining them into one new character, the “moral” of the sentence was revealed. For example, the first sentence read: “This person could not take care of their valuables” (Conglaizhe, bei bukexing). If the boys combined the words for “person” (zhe) and “valuables” (bei), the new word they formed was “gamble” (du). The moral of the sentence is this person could not preserve their valuables because they gambled. In this manner, the riddle went on to talk about people who became greedy, then poor, and then turned to stealing. It was clearly a message upholding conventional morality of the kind that was often taught in China’s schools in the late Qing. The secret to solving the riddle was to find the key character of bei that appeared in each sentence and to combine it with another character in close proximity. An adult might be able to quickly solve this riddle, but for boys of nine or ten, it must have presented a good challenge. I wonder if Teacher Xu assigned groups of perhaps two boys to each sentence and formed a competition to see which group would be the first to find the hidden meaning? It must have been a fun classroom exercise and also a good basis for a discussion of moral behavior and the consequences of not following moral actions. This was very much in the Confucian tradition of understanding the importance of one’s actions.

The third item in Teacher Xu’s collection was not intended for classroom use. It was a recipe of an herbal medicine to help one sleep. It was a compound of many natural roots and powders that could be found in almost any pharmacy in China in those days. Actually, many Chinese communities in the West (often called “Chinatowns” in English) these days also have pharmacies that sell traditional medicines and herbs such as those mentioned in Teacher Xu’s recipe. This item tells us that most likely Teacher Xu acted as a “doctor” or a medical adviser for those who consulted him on medical matters. In the late Qing and early Republic, from the 1890s to the 1930s, it was a typical practice among the common people of China, called ordinary people (pingmin), to approach any person who was literate and ask them for advice on all sorts of matters. Since fully literate people were few, it was assumed that educated people had knowledge on all sorts of subjects, including fortunetelling and medicine. It is also possible, of course, that Teacher Xu needed the recipe for his own use.10

Possibly Teacher Xu was also a fortune teller; he gave predictions for his students’ futures, as we will see later, and also earned extra income for that service. If we look at the full page of the teacher’s income mentioned above, we see that the teacher at the Huamin School also had other teaching jobs in order to earn enough to live on.

To return to our discussion of the classroom, I believe Teacher Xu was a keen observer of the students in his class and that he enjoyed their personalities. I draw this conclusion because on one of the latter pages of his collection, he wrote the names of some of his students and then gave a short predicition about their futures. For example, for one student he wrote: “Wang Kemin, Sun and moon shine forth, Good Fortune” (Riyueguang, fuxiang). For another student he wrote: “Dong Yongfa, Cold and heat follow naturally, Good Prospects” (Hanlai shuwang, lutian).

A boy named Wang Jufu may have been Teacher Xu’s favorite student, because he wrote Wang’s name and address on the last page. He wrote: “Wang Jufu eleven years old, originally from Pingding County, Shanxi Province. Living in Jilin Province, Henan Road, Hexingyin Department Store.” We can see that young Wang was probably living with his parents above the family store (a small shop could also call itself a department store), so this was likely a working-class family that had moved from Shanxi west of Beijing all the way east to southern Manchuria. In the late Qing, the economy of Manchuria was better than were economic and living conditions in Shanxi.11

Another favorite student was Wang Bingming. On the back cover of Teacher Xu’s classroom materials, young Wang practiced writing his name. He wrote it four times and began to write it the fifth time, but wrote only the first two characters of his name. Why did he write his name on the back cover? I hypothesize that Teacher Xu decided to give the book to Wang, perhaps because he was such a good student or perhaps because the riddle intrigued him so. I also make a great (but logical) leap in interpretation by assuming that Teacher Xu gave the book to young Wang in about 1883 when Wang was probably about twelve years old (the typical age of elementary school students in most classrooms at the time). If the book had been copied out in 1880, then it had been in use for three years and the thin paper could have been showing a lot of wear.

I like to think that Teacher Xu epitomized the Confucian ideal of a teacher who was caring and willing to engage his students intellectually. In practice, we know that elementary teachers were often strict taskmasters who might even beat poorly performing students. But the writings about his students that Teacher Xu put in his classroom materials indicate to me that he was a gentler and more open teacher. If so, he was following the words of Confucius, who said, “If three of us walk along, one of my companions will be my teacher.” Confucius felt we should always be open to learn from others.12

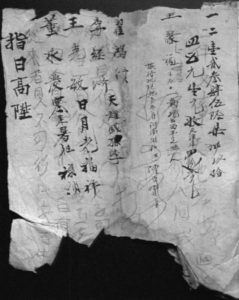

used in class with his students. It challenged their ability to recognize and manipulate written characters, while also teaching a moral lesson. Source: Photo by author.

“If three of us walk along, one of my companions will be my teacher.” Confucius felt we should always be open to learn from others.

Young Wang treasured the book he had received from his teacher as he grew older and gradually became bald. About thirty-seven years later, when Wang would have been forty-nine years old, the book came into the hands of another young boy. Possibly Wang gave it to this young student, or for some other reason it passed into the possession of the student. When he received the book, this student used a pencil to write the date on the front cover: “20 nian, 6 yue, 27 ri” (June 27, 1920). This student did not write his name in the book, but he used the same pencil to tell us something about the book. On the inside of the front cover he wrote: “This is the book that retired bald-headed Wang used to read so earnestly.”

In my analysis, this set of materials used in an elementary classroom in China had a life of three generations. The first generation was when Teacher Xu had it copied out, perhaps in 1880. He used it in the classroom and added his own notes about his students, their personalities, and in one case their address. The second generation of the book began about 1883 when Teacher Xu decided to give the book to Wang Bingming. It seems logical to assume that boy Wang became the bald-headed and retired Wang who was often seen reading the book by the young student with the pencil who received it in 1920.13 It is nice to think that the materials in the book were important to all three of its owners. In a good Confucian manner, they all respected their elders and teachers, and they diligently read the text.

This text that was so important to a number of people was acquired by me in 2005. I feel grateful myself to possess this treasured book. But logically, it passed through other hands before it reached me. For example, if the young student with the pencil was twelve years old in 1920, then he was fifty-eight years old in 1966 when the Cultural Revolution swept through China. That was not the time to have an example of “feudal thinking” such as this book.14 If I continue guessing about the life of this book, I could think that it was hidden away during the Cultural Revolution and later found by relatives of the person who hid it. Most likely at that point, they turned it over to a paper recycler who put it into the market system that would eventually see it turn up in Beijing’s Panjiayuan Market.

It could have happened that way. I feel grateful to have the book in my collection and to be able to do research and analysis of its probable history. The materials in the book and its long history of transmission from student to student (I am also a student of history) follow the honored Confucian tradition of respect for precedent, for the written word, and for the relationship between teacher and student. Now that China is officially embracing Confucian teaching and is suggesting it can be the basis for constructing a better international community, Teacher Xu’s book takes on renewed importance for those of us who read it and appreciate its contents.

NOTES

1. The shop put its stamp in red on the cover. It was called the Zhizhoutang. The shop’s trademark was a round jade disk they called “The Translucent Jade Disk (Bi Jin Ming). They gave the name of their city as Panshi, a city in south Manchuria (then called the Three Eastern Provinces [Dongsansheng]), to the south of Jilin City and to the north of Fengtian City (present-day Shenyang city in Liaoning province).

2. Three Items for Mr. Xu (Xushi sanzhong) is 93 inches (24.76 cm) h x 83 inches (22.22 cm) w, which gives it a square shape, similar to Korean string-bound books. A woodblock publication with the same title appeared in the early Qing, annotated by Wang Xiang and edited by Xu Shiye. It was reissued in 1821 by the Fuchuntang. Thus it could be that the copyists used this “classic” title for the work they copied, and the name of the teacher discussed in this paper was not in fact Xu. These published works always contained a copy of the Thousand Character Classic.

3. The hand-written copied text discussed in this paper and a more complete analysis of its contents is in my book, Ronald Suleski, Daily Life for the Common People of China: Understanding Chaoben Culture (Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2018), Chapter 4.

4. For a good discussion of traditional education under the Qing, placed in the context of Chinese society at the time, see Richard J. Smith, The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

5. Estimates of literacy and functional literacy vary widely, from 5 percent to over 50 percent. A thoughtful and well-documented consideration of this topic is in Cynthia J. Brokaw, Commerce in Culture: The Sibao Book Trade in the Qing and Republican Periods (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007), 559–568.

6. This information is taken from another hand-written book I bought titled Riches Bestowed (Qianjinfu). This is a work of seventy-four pages written in a very good calligraphic hand on poor-quality handmade paper. It is 81 in (21.59 cm) h x 51 in (13.34 cm) w, a size likely intended for a reference book. This is probably a Republican- era (1912–1949) text, and the ink still looks crisp. The quality of writing ink used by writers in China was usually very high.

7. Printed editions of the Thousand Character Classic are ubiquitous in China today. Some are adapted as children’s picture books, while others contain examples of the fine calligraphy for use in improving one’s own calligraphy. The Thousand- Character Classic was one of the most popular texts used in traditional-style elementary education. A version containing Chinese and English is Evelyn Lip, 1,000 Character Classic (Singapore: SNP, 1997).

8. A discussion of the texts used in private academies and schools in traditional China is Ōsawa Akihiro, Keimō to kyogyō no aida: dentō Chūgoku ni okeru chishiki no kaisōsei (Between Elementary Education and Official Office: The Class Basis of Knowledge in Traditional China),” Tōyō bunka kenkyū (Research on Asian Culture), (no. 7, March 2005), 27–65.

9. Interesting points about riddles in China, both traditional and contemporary, are in Wang Fang, ed., Zhongguo miyu daquan (Collection of Chinese Riddles) (Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe, 1983), 1–16, 544–556.

10. The recipe called for domestic ginseng, 5 fen (lucan wufen); bamboo leaves, 5 fen (zhuye wufen); anther, a medicine extracted from flowers, 5 fen (huafen wufen); brown sugar, 4 or 5 fen (chitang sifen wufen); ashes, 5 fen (yanhui wufen); Korean ginseng, 5 fen (Gaolican wufen); hot wine, 1.5 to 2 jin (shaojiu jinban er jin); chocolate vine, 5 fen (mutong wufen). The instructions following it said: “Cook this repeatedly for x hours over seven days, and then take it for three or four days. After three days the body will x x (unclear characters). Then who would be unable to sleep!” (Zhu erwang x shi, x qitian, baohaoqian sansitianhao, housantian x fa, kongbu nengshuijinghu).

11. The difficulties of life in Shanxi in the late Qing and early Republic are detailed in Henrietta Harrison, The Man Awakened from Dreams; One Man’s Life in a North China Village, 1857–1942 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005). For a contrast of the growing economy in Northeast China see Ronald Suleski, Civil Government in Warlord China: Tradition, Modernization, and Manchuria (New York, Peter Lang, 2002).

12. This well-known quote is taken from the Analects, the book that contains a record of the discussions that Confucius had with many of his students. It is in the Chapter on Expounding Ideas, Book Seven, Section 21. There are many English language translations of this phrase, and differing translations for the sections of the Analects. The version of the Analects I consulted was The Four Books with Chinese-English Translation (Taipei: Wenyou shudian, 1955), 51-52, an unauthorized pirated copy of a translation made by James Legge as The Four Books, and in China published in 1930. Legge (1815–1897) carried out his translations from 1841 to his death in 1897. His works were originally published in England, and his first translation of the Analects was published in 1861. In the twentieth century his translations were widely pirated in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. A contemporary interpretation of this phrase, meaning we should apply it in its broadest possible terms, is in He Jun, Bushe Lunyu (Don’t Discard the Analects) (Shanghai: Huadong shifan daxue chubanshe, 2017), 127. Dr. He is a well-respected Confucian scholar in China today.

13. My hypothetical chronology for the book is based on the following logical associations: I took the one clearly written date of 1920 on the inside front cover, and calculated back three generations, taking thirty years as a generation. Thus, Teacher Xu may have been born about 1840. He may have been a forty-threeyear- old teacher in 1883 when he gave the book as a memento to twelve-year-old Wang Bingming, the boy who became bald-headed Wang. When the final student received the book in 1920, bald-headed Wang might have been forty-nine-yearold, and the boy who wrote the date on the book might have been between twelve to fifteen years old, judging from the handwriting.

14. During the Cultural Revolution, people who had written materials that might be considered to uphold feudal thinking, tried in various ways to protect themselves while still keeping their materials. Some of them wrote slogans praising Chairman Mao in the margins, to show they were in sympathy with the political tenor of the times and that they did not support feudal thinking. Several books in my collection show this practice. One of them is Ruili Company Accounts (Ruili qingchaozhang). The Ruili Company operated as a bank or money lender in Shandong province between 1924 to 1932. The record of their operations that I have is a 298-page book of 71 inches h x 6 inches w. A hastily brushed anti-feudal phrase in this book (page 177) is “Mao Zedong Thought is the steam engine leading forward our revolutionary thinking.” (Maozedong sixiang shizhiyin geming qianjinde sixiang huochetou).