Chinese tourists can be a real contributor to the global economy and world peace. China needs the world, and the world needs China.

—Zhang Guangrui, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences1

By the end of this decade, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) forecasts that the People’s Republic of China (hereafter referred to as China) will be sending 100 million tourists abroad each year.2 By then, China is expected to be the world’s largest tourist-generating country.

How is that possible? Before 1978, China was pretty much closed to the outside world. Few Chinese citizens were allowed to travel to other countries. Those who did were either businessmen, government officials, or students. Taking a pleasure trip abroad was unthinkable unless it was disguised as a legitimate trip. All that began to change in the 1990s when China adopted a unique tourism policy. China’s Approved Destination Status (ADS) Policy allows overseas pleasure travel by its citizens in tightly controlled groups and only to countries (and territories) approved by the government. Tourist destinations around the world hailed this move. Imagine the world’s most populous country of more than 1.3 billion people spreading its growing wealth around the globe! Lost in the euphoria was the policy’s big limitation: Chinese citizens were not able to go where and how they wanted. In this article, we examine China’s ADS policy.

China’s policy on outbound tourism is an important topic to study because international tourism has become an economic and social force of global significance. Tourism, if developed in a sustainable way, can be a positive agent of economic and social change and a potential weapon in the fight to alleviate global poverty. China is the world’s most populous country and its second-largest economy; its policies now have the potential to generate big, rippling economic and social impacts throughout the world. Tourism can also promote better international understanding and global peace.

Our article can be used in economics, geography, political science, anthropology, and sociology courses to introduce students to the importance of international tourism, as well as ongoing issues involving China’s economic development. In college and high school AP economics classes, students would learn about issues surrounding the liberalization of international trade in services. Tourism is a particularly good example, as it is the largest item in international service trade. In the high school AP human geography class, students might want to follow up on our analysis by exploring the tourist attractions of various countries around the world and why some countries might be more attractive to Chinese tourists than other countries. For example, students could study the rules and regulations governing the selection of World Heritage Sites (what they are and how they get on the list, etc.). Students in anthropology and sociology classes might be encouraged to assess the sociocultural impacts of mass tourism on tourist receiving and sending countries. Students in political science classes may want to follow up on how tourism is used as political leverage in international relations. The sudden drop in the number of Chinese tourists visiting Okinawa, Japan, in fall 2012 as a result of the Japan-China dispute over the Senkaku Islands would be a natural follow-up.3 China’s ADS policy and the big surge in Chinese tourism are clearly interdisciplinary topics, and they may be best suited for interdisciplinary courses, such as Asian studies or global studies, particularly because these courses are less bound than disciplinary courses by specific, fact-based, state instructional standards.

Background

For most people, tourism means travel for personal pleasure. That is not how the UNWTO defines it. Tourism is travel away from one’s usual place of residence for less than a year for reasons other than emigration or employment. In 2010, 51 percent of globe-trotting tourists were traveling for fun, and another 15 percent were traveling on business and professional trips. Visiting friends and relatives, travel for one’s health, religious pilgrimages, and “other” made up the rest.

International tourist arrivals have grown to impressive levels and now have a tremendous impact on the global economy. Statistics published by the World Tourism Organization show that international tourist arrivals worldwide reached 983 million in 2011, compared to 25 million in 1950, and have more than doubled over the past twenty years. International tourists spent an equivalent of over US $1 trillion dollars in 2011, excluding passenger transportation costs, compared to just US $2 billion in 1950.

Immediately after World War II, tourism development was not a high priority among Asian countries. What they wanted was to maximize economic growth by emphasizing the production and export of manufactured goods. Tourism’s role was to bring in foreign exchange (currency) to help pay the costs of industrialization. This meant bringing foreign tourists in but not allowing their own citizens out (travel bans). Countries also imposed limits on how much foreign currency a traveler could obtain (currency restrictions), which effectively limited how much money a traveler could spend on foreign travel.

Japan, which was rebuilding its economy in the two decades after the end of World War II, did not allow its citizens to travel abroad on pleasure trips until 1964, after the conclusion of the Tokyo Olympic Games. After the travel ban was lifted, Japan continued to impose currency restrictions on Japanese travelers, which remained in place until the late 1970s. South Korea did not fully lift its ban on outbound pleasure travel until 1989, after the conclusion of the 1988 Olympic Games in Korea. When both countries finally lifted their travel restrictions, Japanese and South Koreans took to foreign travel with great enthusiasm. Since the 1970s, tourism has grown much faster in the Asia-Pacific region than in other regions of the world. The lifting of travel bans, especially in Japan, was one of the reasons why tourism grew so rapidly in the region.4

Compared to its Asian neighbors, China is a latecomer to international tourism. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), China was an inward-looking country in economic and cultural turmoil. With the 1976 death of Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China, and the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution, China adopted the Four Modernizations Policies, one of which emphasized the opening of foreign trade. As in other areas of economic policy reform, China’s entry into international tourism was gradual. Initially, China permitted inbound tourism only, followed by inbound and domestic tourism and finally outbound tourism.5

China experimented with outbound tourism in the early 1980s when citizens from Guangdong Province were allowed to travel to nearby Hong Kong and Macau in organized tours to visit relatives. Residents from other provinces were later permitted to join as long as they had relatives or friends in Hong Kong and Macau. Beginning in 1990, Chinese citizens were also allowed to travel to Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand for family visits. The catch was that travel expenses to all five destinations had to be paid by the hosts to prevent the outflow of scarce foreign currency. Eventually, travelers were allowed to pay their own expenses, paving the way for more people to travel abroad.

In 1995, China’s government formalized the ADS system under which Chinese citizens could travel in organized group tours to countries the government had approved. ADS is achieved by bilateral negotiation.6 Unlike Japan and South Korea, which placed no restrictions on where their citizens could visit after their travel bans were lifted, China’s unique outbound tourism policy is selective. It is both liberalizing and restricting. Only selected, government-approved travel agencies in China can sell overseas travel packages to ADS countries. In turn, approved countries must issue a special ADS visa. Chinese tourists can apply for ADS visas as a group as part of their tour packages. In sum, China’s ADS policy enables an increasingly affluent Chinese population to travel abroad at relatively low cost and with few hassles, though not necessarily to the countries of their first choice.

ADs Policy: Purpose

Why did the Chinese government decide to adopt such an unusual policy that eases and yet still restricts travel to its own citizens?7 The easing component is not so difficult to understand. China has been undergoing dramatic changes. Since 1978, the economy has transitioned from a centrally planned economic system to one that is more market-oriented. In December 2001, China became a member of the World Trade Organization after opening and liberalizing its economy during the 1990s. Since then, the economy has been growing at a breakneck pace of nearly 10 percent each year. As a result, GDP per capita today is now more than six times what it was twenty years ago.8 The average annual income per capita in China is still very low (US $5,445 in 2011), but this masks a huge discrepancy in income between those who live in the cities and those who live in the countryside. China’s spectacular economic growth has created a vast urban middle class with a strong appetite for leisure travel.9

The government responded to this growing demand by implementing shorter workweeks and more holidays. The five-day workweek became the norm in 1995. In 1999, the government introduced three golden weeks, with each week comprised of seven days of national holidays.10 The specific goal was to encourage domestic travel. Over time, China’s government also made passports easier to get, raised the limit (several times) on the amount of foreign currency travelers were allowed to purchase, and permitted more travel agencies to get into the outbound travel business. The boom in foreign travel was underway.

Still, the Chinese government did not want to loosen its grip over travel too quickly. The government still wanted to minimize the outflow of foreign currency.11 However, huge increases in China’s foreign currency reserves from 2003 and improvements in China’s international trading position have essentially eliminated this objective as a goal of Chinese travel policy. ADS was also seen as a way for both governments to control Chinese citizens’ movements overseas. Among receiving countries, there has always been a concern that Chinese tourists might overstay the number of days allowed on their visas and create an immigration problem. China, too, has been wary of illegal Chinese immigration to ADS countries.12 The 1999 ADS agreement between China and Australia illustrates how ADS agreements can allay those concerns.

The Australia-China ADS agreement imposed stringent controls on the issuance of passports and exit visas by China and tight controls on entry visas by Australia.13 On the Chinese side, only “authorized travel agencies” approved by the Chinese National Tourism Administration could sell overseas tour packages to Australia. Chinese guides must lead tours. A tour leader who has had too many overstayers can be suspended or banned from escorting future tours to Australia.

On the Australian side, the government of Australia agreed to accept group visa applications only from China’s authorized travel agencies. ADS visas were valid only for the duration of the group tour, with no possibility of extension or status change once the group arrived in Australia.

In addition to government rules, Chinese travel agencies also developed their own controls to discourage overstays. Though not required by either government, Chinese travel agencies unilaterally required sizable cash bonds from Australia-bound tourists to be refunded upon return to China.14 Tour guides also kept the passports and tickets of tour members. The combination of formal and informal controls resulted in relatively few visa violations. In 2009–2010, the non return rate among Chinese tourists visiting Australia on ADS visas was 0.12 percent, compared to 1.35 percent for all foreign visitors.15 Most importantly, Chinese tourists now constitute Australia’s most valuable source of spending by international visitors. For both countries, ADS has been a success story.

Which Countries Got ADs

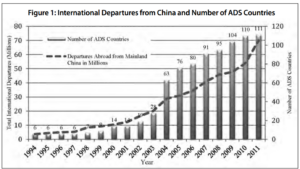

Table 1 provides a list of countries/destinations that have negotiated and implemented ADS agreements with China. Between 1983 and 1993, the list included only seven countries/destinations, all of them in Asia. After 1994, the list of ADS countries expanded rapidly. Currently, more than 110 countries have implemented ADS agreements with China.

ADS designations were not handed out randomly. For China, negotiating ADS agreements with its neighbors was important because of its potentially positive impact on its relations with them. Shorter distances to nearby countries also meant less expensive vacations for Chinese travelers.

There are also indications of clustering of awards by region. For example, a group of European countries, including the members of the EU, obtained ADS around 2004. Many South American and Caribbean countries were granted ADS between 2005 and 2009. Grouping of countries reduced negotiation costs. It also allowed Chinese travelers to visit several countries in a particular region on a single trip, and thereby both saving money and having a variety of experiences.

Still, it is not obvious why and when some countries successfully negotiated agreements and others did not. We offer one possible explanation. Since the Chinese government regards granting ADS to a country as a concession favoring the grantee country, China may have been using ADS as soft power to gain political concessions from potential grantee countries when it served its national interest. For example, it was reported that China granted ADS to the South Pacific island nation of Fiji in return for not recognizing Taiwan diplomatically.16 Indeed, among the twenty-three countries that currently recognize Taiwan, not one has been granted ADS by China. Despite its penalization of countries recognizing Taiwan, China granted ADS to Taiwan in 2008.17

More evidence exists that China employs ADS both as a carrot and a stick to gain political advantage. The evidence consists of the voting records of United Nations members on eighteen votes during the fifty-eighth session of the 2003 United Nations General Assembly.18 Most of the votes were on global security issues. Analysis of these voting records indicates that countries that voted more frequently in agreement with China were more likely to have received ADS.

Impact of ADs on Chinese outbound Travel

Figure 1 displays the total number of ADS countries by year of award and annual Chinese departures abroad between 1994 and 2011. During the first ten years of the ADS program, the number of Chinese traveling abroad grew at an average rate of 22 percent per year. The comparable rate of increase for Japan during the first ten years after the lifting of its travel ban was 40 percent per year. Between 1994 and 2011, Chinese outbound travel grew at a slower rate of 20 percent per year on average, compared to Japan’s 29 percent over a comparable period. It would be tempting—but probably unwise—to conclude that China’s growth was slower than Japan’s because it had adopted a selective and drawn-out approach to travel liberalization. For one thing, China began its liberalization process with a larger number of outbound tourists than Japan: 4.5 million for China in 1995 versus 128,000 for Japan in 1964. In any case, what matters more to tourist destinations are the actual numbers of tourists and how much the typical tourist spends. The gap between the numbers for Japan and China is striking. In 1980—sixteen years after Japan lifted its ban on overseas pleasure travel—3.9 million Japanese traveled abroad. By comparison, the China Tourism Academy reports that 70 million Chinese traveled abroad in 2011, sixteen years after ADS was formally adopted.19

How did ADS affect individual countries that received ADS? For the answer, we can compare Chinese tourist arrivals in individual ADS countries before and after receiving ADS. A recent study of outbound Chinese travel used Chinese tourist arrival data from seventeen ADS recipient countries that received ADS between 1998 and 2003. It compared each country’s average annual growth rates three years before and three years after receiving ADS designation.20 The study found the following results. First, there were big differences in the growth rates of Chinese tourist arrivals in these ADS recipient countries both before and after they received ADS. In other words, some destinations were simply more attractive to Chinese tourists than others. For some countries, being awarded ADS is not a guarantee of a flood of incoming Chinese tourists. Second, in most of these countries (fourteen), growth rates of Chinese visitor arrivals post-ADS exceeded the growth rates pre-ADS.21 Third, only five of these countries had pre-ADS growth rates of Chinese tourist arrivals that exceeded the growth rates of overall Chinese outbound travel over the same years, compared to eleven post-ADS. Overall, ADS appears to have spurred Chinese travel to ADS countries.

Two separate studies also employed statistical techniques that helped identify the potential influences of other factors besides ADS that might have affected Chinese travel to these ADS recipient countries.22 Both studies confirmed the positive impact of ADS on Chinese visitor arrivals. Both also found that the designation of a new ADS country diverted Chinese tourists from non-ADS and previously designated ADS countries to the new ADS country. That should not be a big surprise. Which countries got ADS reflected the preferences of the Chinese government and not necessarily the preferences of the Chinese consumers. As more countries were approved, Chinese consumers could change their minds and visit the countries they preferred.

Conclusion

ADS is a preferential travel liberalization system. While it has spurred Chinese travel abroad, it has also restricted opportunities for Chinese consumers to travel to destinations they might otherwise have preferred. As more countries conclude ADS agreements with China, the value to the Chinese government of having a preferential policy diminishes. Even the Chinese recognize this.23 In the meantime, with more than 110 countries and territories that have already implemented ADS, including the most popular destinations, Chinese citizens currently have a tremendous number of destination choices. Since 2003, mainland Chinese have been allowed to travel to Hong Kong and Macau on an individual basis. Perhaps a change from group to individual travel will be the next phase of outbound travel policy reform in China.

In 2009, the number of Chinese who traveled abroad, as a percentage of the nation’s population, was just 3.5 percent. The World Tourism Organization estimates that the global average was 11.5 percent in 2000. With the Chinese only beginning to travel internationally, we have a clear conclusion: A lot more Chinese are coming!

Notes

1. Mark Magnier, “Chinese Tourists Export a Mix of Cash and Brash,” Los Angeles Times, June 26, 2006, accessed July 30, 2012, http:// tiny.cc/d6dvuw.

2. This forecast includes travel to Hong Kong and Macau.

3. Chester Dawson, “Japan’s Spat With China Takes Big Toll on Tourism,” The Wall Street Journal (WSJ.com), November 27, 2012, accessed December 2, 2012, http://tiny.cc/dxdvuw.

4. James Mak and Kenneth White, “Comparative Tourism Development in Asia and the Pacific,” Journal of Travel Research, 31, no. 1 (1992): 14–23.

5. Guangrui Zhang, China’s Outbound Tourism: An Overview, WTM-Contact Conference (Beijing: Tourism Research Center, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 2006).

6. ADS agreements differ in some of their provisions. Although one of the main advantages of ADS is the reduced cost of group visa processing, the 2007 Memorandum of Understanding between China and the US allowed the US to require one-to-one, in-person visa interviews at US consulates in China.

7. US citizens wishing to visit Cuba must obtain a special license; see James Mak, Tourism and the Economy: Understanding the Economics of Tourism (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2004). The US began to allow travel to Cuba by Cuban-Americans in 2009 and by some students and missionaries in 2011. Despite US State Department travel warnings about potentially unsafe countries, Americans typically travel as tourists wherever they please.

8. World Bank, China Overview, 2012, accessed August 4, 2012, http://tiny.cc/73dvuw.

9. We define a middle-class household in China as one with an annual income between US $10,000 and US $60,000.

10. In 2008, the third golden week was reduced to three days.

11. Wolfgang Georg Arlt, China’s Outbound Tourism (New York: Routledge, 2006), 42.

12. Ibid, 43.

13. Trevor H.B. Sofield, “China’s Outbound Tourism to Australia,” Touristics 18, no. 18–11, 2002.

14. This practice was later adopted for Chinese travel to the European Union.

15. Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Fact Sheet 58—China: Approved Destination Status, July 5, 2011, accessed July 31, 2012, http://tiny.cc/u4dvuw.

16. Mark Magnier, 2006.

17. In January 2005, China granted approval to Canada to apply for ADS status, but ADS was not granted until June 2010. Several political disputes between Canada and China appeared to have delayed China’s decision to grant ADS to Canada. Canada threatened to take the matter to the World Trade Organization; see Jon Grenke, Approved Destination Status: New Zealand, Australia and Lessons for the Canadian Immigration System. Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of public policy (Burnaby, British Columbia: Simon Fraser University, approved March 15, 2006); see also, Joy C. Shaw, “Oh Canada, Here Come the Chinese Tourists,” China Real Time Report-WSJ, December 4, 2009, accessed October 17, 2012, http://tiny.cc/l5dvuw.

18. Shawn Arita, Sumner La Croix, and James Mak, How Big? The Impact of Approved Destination Status on Chinese Travel Abroad, University of Hawai`i at Manoa, Department of Economics Working Paper No. 12–12 (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i at Manoa, 2012).

19. Most of these trips were to Hong Kong and Macau. In 2010, 63 percent of outbound trips from mainland China went to these two destinations.

20. Shawn Arita, Christopher Edmonds, Sumner La Croix, and James Mak, “Impact of Approved Destination Status on Chinese Travel Abroad: An Econometric Analysis,” Tourism Economics 17 no. 5 (2011): 983–996.

21. Three countries—the Maldives (Indian Ocean tsunami), Nepal and Sri Lanka (civil war)—had lower post-ADS tourism growth rates due to natural disasters and war afflicting their tourism sectors.

22. Arita et al. (2011) and Arita et al. (2012).

23. Zhang, 2006.