By Warren A. Stanislaus, University of Oxford

“There are no Black British-Japanese connections, so I wouldn’t spend your time looking.”

This was the guidance I received from a professor at a conference upon seeking advice on related research project ideas. As I argue in a commentary for the Royal Historical Society, such perceptions are perhaps unsurprising, as Black British history is especially believed to be limited in its spatial and temporal expansiveness. Consequently, Black British-Japanese linkages are imagined to be, well, impossible. To be sure, this can be situated within broader discourses of Afro-Japanese or Afro-Asian encounters that are regularly characterized by narratives of incompatibility, irreconcilability, or rift, which inadvertently obscure and preclude the discovery of histories that don’t neatly fit these frameworks of understanding—something that I discuss in more depth in an essay at Critical Asian Studies.

Despite observing cultural flows and interactions, not to mention my own journey, which speak to the existence of this “unimaginable” transnational connectivity, I failed to muster up a response and retreated into silence. I was unable to, in the words of Audre Lorde, engage in a “transformation of silence into language and action” for fear of having “what is most important to me…bruised or misunderstood.”

My discouraging encounter with this professor is perhaps a familiar one to others. In an AAS Digital Dialogues panel from July 2020, William H. Bridges IV introduced a similar experience where as a graduate student seeking out a sponsor at a Japanese university, he was told that his proposed research of exploring blackness in postwar Japanese literature “would not be a study of Japanese literature.” Perhaps experiences such as these have meant the loss of many a talented researcher down the infamous leaky career pipeline, or projects that will forever remain unpursued and undocumented—a silence untransformed.

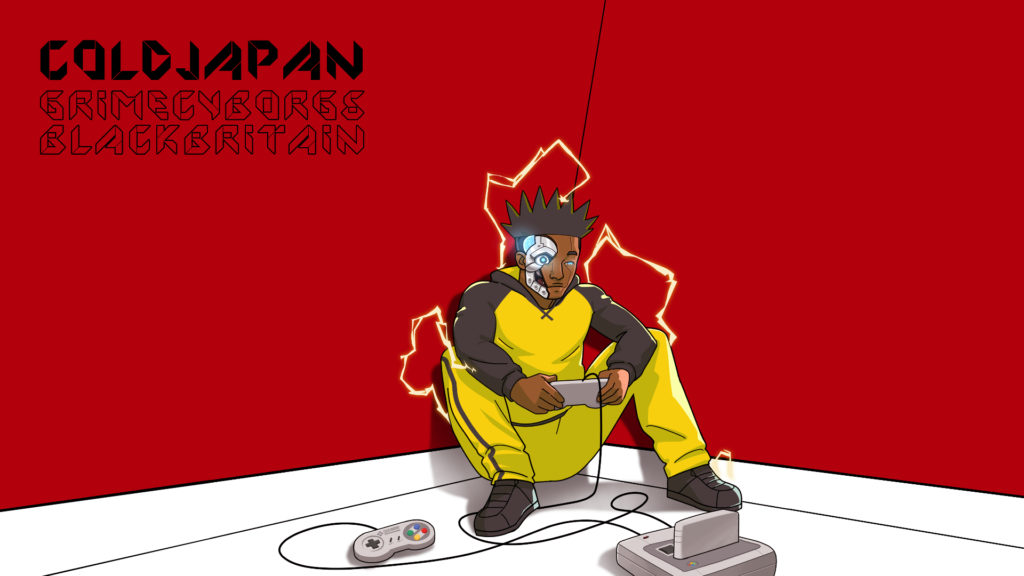

Undeterred, however, I silenced the voices of doubt, and wrote an article, in which one of its contributions is the disclosure of a significant Black British-Japanese interactivity. Published in the Japan Forum journal, “From Cool Japan to Cold Japan: Grime Cyborgs in Black Britain,” is itself a story of a breaking out of the silence.

The article introduces grime, a fast-paced electronic music and style of rap that emerged out of public housing blocks and pirate radio stations in London as an underground DIY subculture in the early 2000s, and traces its roots to an eclectic mix of genres. The sound and themes articulate the alienation and perspectives of Black urban life on the margins of British society. As expressed by Jme, one of the pioneers of grime:

“Before grime, never had a voice

Grew up in Tottenham, I never had a choice.”

(96 of My Life)

Delineating how Black urban life in Britain fused with the wires and worlds of Japanese pop culture and technologies, I disclose how grime artists disassemble and recombine these components to generate their countercultural voice. In other words, we cannot understand Black British youth identity formation in the early 21st century without considering the impact of transnational flows of Japanese pop culture, nor can we talk about the global spread of Japanese pop culture without addressing the questions raised by how “Cool Japan” was recontextualized and remixed in Black Britain. Or to repurpose Bridges’ assertion, “Asian studies matters for Black lives” and Black lives matter to Asian studies.

Drawing inspiration from work by Paula R. Curtis and Tristan R. Grunow’s #AsiaNow piece, which make the case for embracing innovative approaches to digital scholarship and public-facing output in Asian studies, I collaborated with digital artist Jason Adenuga to visualize in the form of an animation several key themes introduced in the article (see full animated visualizer here). The article cover art is a nod to grime artist Dizzee Rascal’s influential Boy in da Corner album from 2003 and its iconic album cover that has been described as a cultural touchstone. The original album cover pictures a black-hooded Dizzee literally sat in the corner in front of bright hazard-yellow color walls and futuristic “origami” font text, while flicking up devil horns and gazing at the viewer with Mona Lisa-esque following eyes. “It was a way to transmute cultural marginalization into an electrifying jolt of self-affirmation,” writes Gabriel Herrera in a Red Bull Music Academy piece. We chose Hinomaru red panels (or perhaps a Poké Ball color palette) and placed a SNES on the floor in the “Cold Japan” article visualizer remake to illuminate the links with an imagined Japan of the future and Japanese pop cultural artifacts in powering this Black British voice, which transcends the silent margins. Regenerated by electrifying jolts from Japan, the “boy in da corner” is transformed into the cold “cyborg in da corner.”

Beyond referencing the original yellow panels, the bumblebee yellow-black hoody that our “cyboy” wears is also an allusion to Bruce Lee’s famous jumpsuit, also memorably donned by the actor Taimak as Bruce Leroy in the 1985 movie, The Last Dragon. Such easter eggs hidden within the artwork are intended to bring to mind much wider Afro-Asian connections, for example, how Black audiences across the African diaspora have long identified with and been inspired by the underdog hero stories of Hong Kong martial arts cinema—a phenomenon and broader historical context from which grime draws. Further, while there can be a tendency to view Afro-Asian cultural exchanges, discourses, and shared agendas as disparate sparks that are but fleeting moments of connectivity, the visualizer speaks to continuity and overlap.

This was one of the goals of the Black Transnationalism & Japan Conference hosted online in October 2021 by the Nissan Institute of Japanese Studies, University of Oxford, where I had the opportunity to present the “Cold Japan” paper. The conference conceptualized an extended and continued current of Black-Japanese encounters, an alternative timeline if you will, which reveals a “rich and intertwined transnational history…that often countered the state and that were invisible from a solely state-centric lens.”

In many ways, my participation in the conference itself was also the culmination of an alternative timeline of guidance that ran alongside and countered the experience introduced at the start of this post where my ideas were dismissed. During the conference that was conducted virtually, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself on a panel sandwiched in between William H. Bridges IV and Marvin Sterling with Mateja Kovacic as the discussant. Discovering a book on Afro-Japanese Cultural Production edited by Bridges and Nina Cornyetz affirmed that these research topics are significant and do belong, while both Sterling and Kovacic had kindly agreed to offer mentorship in the form of feedback on drafts of my article, assuring me that it is indeed worth transforming “silence into language and action.”

This is exactly why initiatives such as the AAS Mentoring Workshop for Black Graduate Students in Asian Studies are vital. As a graduate student participant in the 2021 session, I heard the voices and experiences of diverse Black scholars, senior and early career, across multiple subfields of Asian Studies. The workshop provided a necessary space to empower junior Black scholars, such as myself, to find our voice in Asian Studies.

I will close with the powerful call to action presented at the aforementioned AAS Digital Dialogues, where Bridges urged us as scholars in Asian Studies to consider how Black lives and blackness matters to our fields and to “listen when the archive makes this argument for itself.” With those words in mind, I hope you will take a moment to check out the “Cold Japan” digital playlist I curated on Spotify and YouTube so that you can hear the voice of grime…hear the Black British-Japanese connectivity, because the archive makes the argument for itself.

Read Warren’s article, “From Cool Japan to Cold Japan: Grime Cyborgs in Black Britain,” and the Japanese translation at Japan Forum. Watch Warren’s talk at the Asia Society, Japan.

Warren A. Stanislaus is a PhD Candidate in modern Japanese history at the University of Oxford’s Faculty of History. Originally from South East London he has spent 12+ years in Tokyo, speaks fluent Japanese and advanced Mandarin Chinese. Previously, he worked as a researcher at Asia Pacific Initiative, a Tokyo-based think tank. He received a BA in Liberal Arts from ICU and is currently an Associate Lecturer at Rikkyo University’s Global Liberal Arts Program. In 2019, he was named No.3 in the UK’s Top 10 Rare Rising Stars awards.