Anna Stirr is Associate Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawaii, and author of Singing Across Divides: Music and Intimate Politics in Nepal, published by Oxford University Press and winner of the 2019 AAS Bernard S. Cohn prize for a first book on South Asia.

To begin with, please tell us what your book is about.

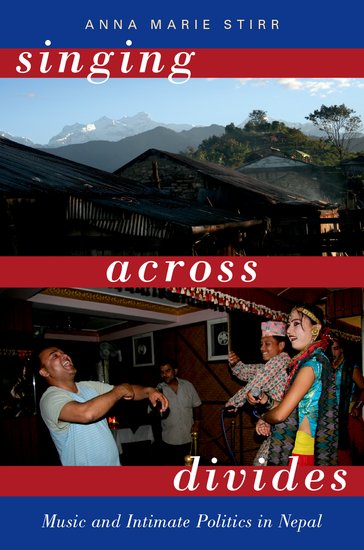

My book is about the importance of a genre of Nepali sung poetry called dohori in the everyday social relations among different groups in Nepal today. Dohori is improvised, dialogic singing, in which a witty repartee of exchanges is based on poetic couplets with a fixed rhyme scheme, often backed by instrumental music and accompanying dance, performed between men and women, with a primary focus on romantic love. It has roots in multiple indigenous traditions of social exchange. It’s transgressive of dominant social norms, because it promotes love relationships that cross social divides—caste, class, ethnicity, religion. Despite this transgressiveness, it’s also associated with an idealized rural and rustic “national essence,” promoted by the state in the 1980s, and by private institutions and performers since then. As Nepal’s ten-year war between the Maoists and the state security forces spurred migration from villages to cities and abroad, dohori became Nepal’s most popular commercial music genre. Performance venues and recording studios sprung up all over the capital city, their products immediately circulating back to the villages and outward to the diaspora. The book examines how dohori performers intersectionally address micro-level, intimate politics of ethnic, caste, gender, and geographical differences, as it promotes potentially destabilizing interactions across these divides.

What inspired you to research this topic?

I knew I wanted to research song, and rural-urban migration. I’d been doing research and working in Nepal since 2000, so it made sense to do this there. I really wanted to learn how rural-urban migrants gave voice to their experiences, and I also wanted to focus on something that was sort of adjacent to the war but that wasn’t the war itself. Then, while I was in Kathmandu doing an internship at an arts NGO in 2005, I met people from all over Nepal who performed in Kathmandu’s dohori restaurants—nightclub-like establishments with stages, dance floors, and full food and bar menus.

When I had first come to Nepal in 2000 there had been a few such restaurants, but over the years of the People’s War, people had left their villages and towns in other districts for the capital. This increase in rural-urban migration provided both a customer base and a steady stream of talented performers, and from three in 2000 the number of dohori restaurants was up to around 80 in 2005. I went to a dohori restaurant with a flutist friend who was in the band, and was immediately captivated.

From an artistic point of view, I loved the improvised sung poetry of dohori, and I loved the things singers were doing with their voices. The atmosphere of drinking, dancing, and revelry in the restaurants reminded me as much of rural Nepal as it did of other bar scenes—as it turns out, replicating the rural Nepali hill festival atmosphere was the whole point. And from an academic point of view, it was clear that that dohori linked rural and urban Nepal at the intersection of multiple identities, and also allowed participants to experiment with changing, crossing, and combining these identities in new ways. So, I was hooked musically and intellectually right away. My methodology became to get to know people in Kathmandu, at restaurants, studios, and concerts, and then go with them to other places, like festivals and fairs, and their own home villages when they invited me.

What obstacles did you face in this project? What turned out better and/or easier than you expected it would?

The thing that turned out to be much easier than I expected was that I learned to sing dohori, to improvise sung poetic couplets, relatively quickly. I tell the story of my first public performance, in a village, in Chapter 2 of the book. But before I got to that point, I had been listening to recordings for about a year, I’d attended one week of daily outdoor festival performances and then transcribed the lyrics, and I’d been attending dohori restaurant performances in Kathmandu for about two months. I hadn’t done this with the intention of being able to sing it myself, though—I was just trying to understand the form. Then, nearly all the dohori performers I met through my research voiced some variation of “if you don’t learn to sing dohori, your PhD will be worthless.” So, I tried to do it, found out that I could, and kept on learning from everyone else’s feedback.

The main obstacle in the beginning of my research was finding an apartment. Dohori restaurant performances take place from about eight in the evening and sometimes lasted until one in the morning, after which I wouldn’t get home until two. Many Kathmandu landlords did not want to rent to someone who would be coming home that late. There were all sorts of reasons given, from security to the potential bad character of a woman who stayed out after dark, let alone until 2 AM.

I initially lived with one wonderful family who understood my project but nevertheless worried about me constantly every time I was out after nine in the evening. They would lock the door and wait up for me. I didn’t want to cause them any more anxiety, and I wanted to be able to come and go without waking anyone up.

So, I ended up moving to a house owned by a music producer who understood the music scene, late nights, and what I was trying to accomplish. I am staying there again right now as I write. The obstacle of finding appropriate housing was also useful from a research perspective, because I wasn’t the only one in this predicament. Finding a place to live that also allowed them to work easily was a problem that all dohori restaurant performers also faced, so it helped me understand some of their challenges.

What is the strangest/funniest/most outrageous/most interesting story or scrap of research you encountered in the course of working on this book?

What I’ve called “binding dohori contests” are the first thing that comes to mind. In these “song duels,” you improvise couplets back and forth for as long as you can, and the first person who can’t come up with an answer loses. Songs like this can go on for days, with breaks taken to do chores or go to school, and sometimes to sleep, but sleeping is usually the first thing to go. Your opponent is the prize. You win their hand in marriage. In some places, both the man and the woman can marry their opponent if they win. In other places, the man can marry the woman, but the woman can only win money, labor, or material goods from the man. There are all sorts of strategies that people use to get into, then get out of, one of these contests, without having to get married. The most common strategy is to put a “hold” on the song, but then go out of your way to avoid having to take it up again. Actual binding contests that really follow through on marriages are rare these days, but everyone likes to talk about them.

Famous dohori singer Prajapati Parajuli’s story of being caught against his will in a binding dohori contest, winning, and having to run away to avoid marrying a girl, is pretty outrageous. I reproduce it in translation in Chapter 4 of the book. I should say that when I retell that story to other, younger dohori performers, one of the responses I get is “Oh, that old man and his tall tales.” Prajapati is a great storyteller and can play up the melodramatic aspects of any event to great entertaining effect. I do think the basic facts of his story are true. But he may have embellished some of the details.

What are the works that inspired you as you worked on this book, and/or what are some other titles that you recommend be read in tandem with your own?

On music, intimacy, rural-urban dynamics, and song and poetry as social action, some books that inspired me as I was writing were my advisor Aaron Fox’s Real Country: Music and Language in Working Class Culture, Christine Yano’s Tears of Longing: Nostalgia and the Nation in Japanese Popular Song, Alex Dent’s River of Tears: Country Music, Memory, and Modernity in Brazil, and Martin Stokes’ The Republic of Love: Cultural Intimacy in Turkish Popular Music. Barry Shank’s The Political Force of Musical Beauty resonated with what I was trying to say about how pleasure in music and poetry can inspire shifts in how one feels about the micropolitics of relating. Some books that inspired me on exchange and producing relationships were Beth Povinelli’s The Empire of Love: Toward a Theory of Intimacy, Genealogy, and Carnality, and Laura Ring’s Zenana: Everyday Peace in a Karachi Apartment Building.

There are a few other recent books on song in South Asia that might be good companions to this one. Kirin Narayan’s Everyday Creativity: Singing Goddesses in the Himalayan Foothills, Linda Hess’s Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in North India, and Anna Schultz’s Singing a Hindu Nation: Marathi Devotional Performance and Nationalism, all look at singing as social action in different parts of India. Laura Kunreuther’s Voicing Subjects: Public Intimacy and Mediation in Kathmandu isn’t about music, but theorizes voice and mediation in interesting ways, looking at a different set of Kathmandu social worlds than my dohori book does. If the ways dohori crosses social boundaries are what excites you, you might also be interested in Jim Sykes’ new book, The Musical Gift: Sonic Generosity in Post-War Sri Lanka. And the most inspiring new book on improvised sung poetry and micro-macro political connections that I’ve read lately is about migration across the U.S.-Mexico border: Alex E. Chávez’s Sounds of Crossing: Music, Migration, and the Aural Politics of Huapango Arribeño.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a historical and ethnographic project on progressive and revolutionary song and dance in Nepal, from the 1960s through the present. I’m tracing the importance that revolutionary performers give to different forms of love and friendship, since they banned romantic love from their songs and dances back in the 1960s and have yet to welcome it back, with a few notable exceptions. One of the things I’ve been doing for this project is working along with Bhakta Syangtan on a documentary film in memory of a revolutionary singer, Khusiram Pakhrin. Pakhrin was my closest interlocutor in this project until he passed away in November 2017. Some of Pakhrin’s photos from a life spent traveling and performing revolutionary songs can be found at my website.