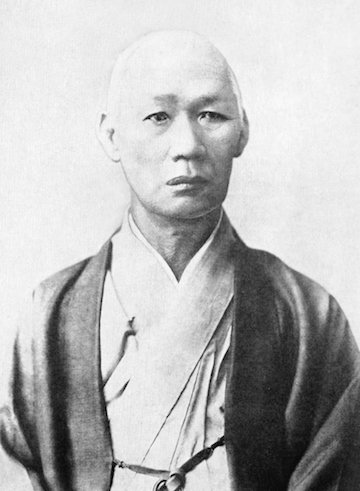

Since 1992, May has been officially celebrated as Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in the United States, and with good cause. The choice of May reflects two historic events: 1) the arrival of the first known Japanese immigrant to the United States on May 7, 1843; and 2) the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869. The former of these dates is more symbolic than it is representative, since Nakahama Manjirō (“John Mung”), the young fisherman who arrived in the United States as a shipwrecked sailor, could not have foretold the waves of immigrants he has since been made to represent.

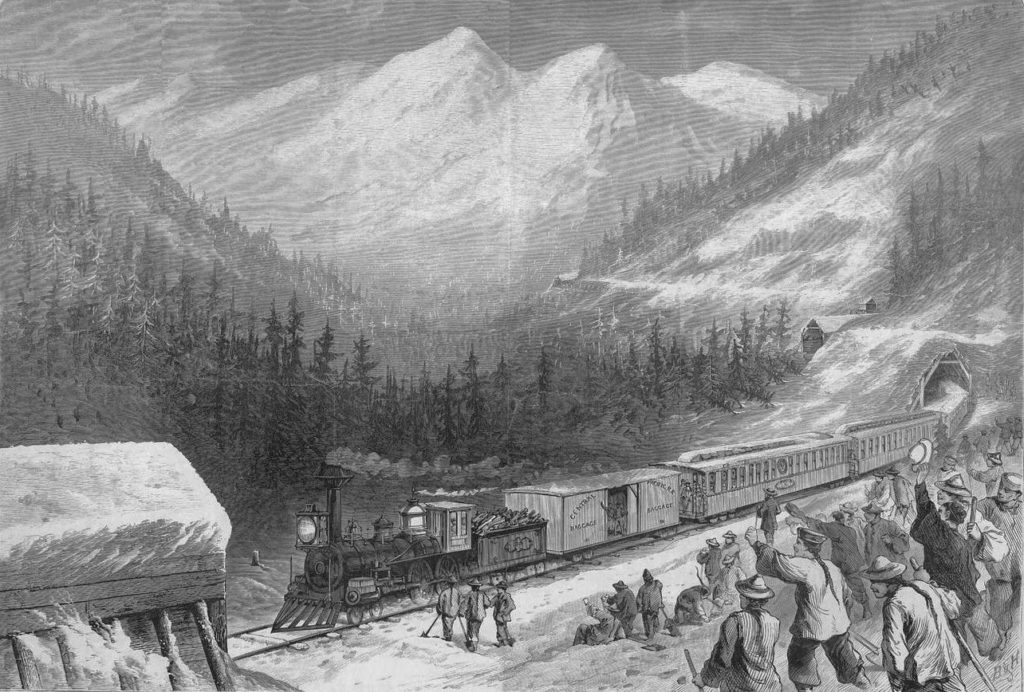

Although Manjirō’s place in history has been secured by the happenstance of his arrival and his subsequent actions as a liaison between Japan and the United States, just the opposite might be said of the group of laborers noted by the second date highlighted in May. The approximately 20,000 Chinese laborers upon whose physical sacrifices the historic Transcontinental Railroad was built are notable not only for their backbreaking labor, but for their erasure from the photos and celebrations of this historic feat. Hired to do much of the hazardous work often shunned by white laborers, the Chinese workers found themselves deliberately excluded from the highly public commemoration upon the railway’s completion. This, too, is part of the heritage of the month. Both of these events in May thus mark two symbolic aspects of Global Asias, the happenstance of shipwrecks and diplomacy, and public erasure. In fact, the designation of this month is meant to remind us of the significance of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders within the fabric of the United States—historically, culturally, politically, economically, and spiritually.

These aspects teach us of the importance of histories and heritage, not as fixed narratives, but as shifting resources in defining a group of people, both internally and externally. This is a turbulent history marked by racial violence, exclusionary legislation, wartime incarceration, and labor strife. This is a heritage suffused throughout the American landscape with food, music, art, media, and spiritual practices. Whether exoticized through orientalist tropes, erased through model minority stereotypes, or normalized through middle-class consumer culture, the heritage highlighted this month asks us to query what such recognition might mean.

The field of Asian Studies plays no small role in contributing to that recognition. This is especially true as Asian Studies embraces the diasporas within its realm—that is, Global Asias. Noting histories and cultures based in, but not limited to, origins in Asia makes the heritage celebrated in this AAPI month rich and dynamic and complex. This is heritage that queries race and its practices. This is heritage that includes the vulnerability and violence of systemic racism—from Yellow Peril to internment to anti-Asian pandemic-fueled scapegoating. And lastly, this is heritage that dots the American landscape, both contributing to regional richness, as well as partaking of different local iterations. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders take their place, erased no longer, seated at tables of their making. This AAPI Heritage Month celebrates the complexities of the Global Asias feast.